Feeding the 40,000 people at the U.N. climate change conference in Paris creates more than a ton of vegetable peels, meat trimmings and unfinished meals. But that waste isn't wasted.

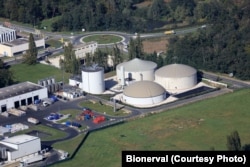

At a plant about 30 kilometers south of the French capital, discarded scraps from the plates of climate activists, academics and government officials are fermented into biogas. The biogas is burned to produce electricity. The residue left behind fertilizes farmers' fields.

"In France we say, what comes from the Earth goes to the Earth,'" said Stephane Martinez, president of Moulinot Compost and Biogas, the small Parisian company handling the waste. "And with (food) waste, it's possible."

In a corduroy jacket and tweed cap, Martinez looks more like a jazz musician than a garbageman. It's an unlikely role for this third-generation restaurateur. But his company is uniquely qualified to help restaurants and other businesses adapt to a law that's changing how France handles its food waste.

Cutting waste, greenhouse gases

The French government is requiring growing numbers of restaurants, supermarkets, school cafeterias and other food servers to separate their food waste from the rest of their garbage. This bio-waste must either be composted or transformed into energy.

Starting in 2016, the law will apply to any establishment that generates more than 10 tons of waste a year. That means every restaurant in France serving more than about 200 customers a day. Violators face an $80,000 fine and two years in prison.

It's part of the country's efforts to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, while also reducing food waste.

Globally, roughly a third of all food produced is lost or wasted, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

In addition to failing to feed the world's nearly 800 million hungry people, it also contributes to climate change. Agriculture and forestry are responsible for nearly a quarter of the world's greenhouse gas emissions.

When food is wasted, "you have emitted greenhouse gases for food that is not eaten," said FAO senior policy officer Alexandre Meybeck. Also, he adds, rotting food is an important source of methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

‘Most beautiful’ compost

The Paris climate conference is the biggest event Moulinot has handled. The company started just two years ago, not long after Martinez did his first experiment with food waste: At one of his three Paris restaurants, he started using worms to make compost.

It was an instant hit in his circle.

"All my (restaurateur) friends said to me, ‘Oh, that's fun what you do, Stephane. I can do the same.' I said, ‘OK, but wait a minute.' "

He had another plan in mind.

Now, his company sends tiny trucks zipping through the cobblestone streets and narrow alleys of central Paris, picking up the trash of the haute cuisine and the not-so-haute, from Michelin-starred restaurants to McDonald's. He also serves 35 schools and a farmers' market.

Each day, Moulinot sends about 6 tons of food waste to a biogas plant south of Paris.

Making biogas is easier than making compost, Martinez says. Or, at least, easier than the compost he wants to make. Worm compost is the "most beautiful you have in the world," as he puts it. But biogas digesters can handle more impurities, he says.

And there's a lot of energy hidden in those table scraps.

According to Serge Verdier, director of waste-to-energy company Bionerval, the waste produced in preparing a meal, plus the uneaten leftovers, will provide enough energy to run your laptop for more than two hours.

More trash power

The French government is encouraging developers to build more biogas plants as part of its plan to lower its greenhouse gas emissions. The government's target of 1,500 plants by late 2017 still would put France far behind Germany, which already has roughly 8,000. But Verdier says it's a step in the right direction.

"The message now in France is to say, it's going to be better in the future, so it's worth investing in biogas," Verdier said.

The company already has invested more than $50 million to build five plants around France. Verdier says Bionerval could triple in size by 2025.

But the food-waste law takes effect much sooner, and it does not appear that France is ready.

"There are not enough biogas plants to treat this kind of waste," said Guillaume Bastide, compost and biogas expert at ADEME, the French environment and energy ministry.

Verdier doubts enforcement will be strict at first for those who don't find someone to handle their food waste.

"The law will say as of January 1 you must do that," he said. "You can imagine, it does not work like that."

Martinez agrees. "We are, in France with this system, at the start."

As for Moulinot, he added, "We have to show a good example. That's what we do today."