Violence between Egypt's Coptic Christians and conservative Muslims has led to calls for tolerance from some unlikely sources.

The allegiance of the men gathered outside a mosque in central Assyut is clear. But the man addressing the rally implores them to embrace those of other religions.

Aboud el-Zomour warns against interfaith violence that just days before in Cairo left 12 people dead.

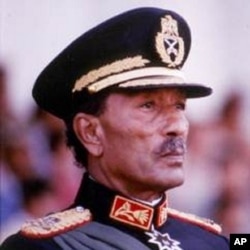

An ex-army officer, former leader of Islamic Jihad, and prisoner for nearly 30 years for his role in killing the perceived infidel President Anwar Sadat, al-Zomour now presents himself as a messenger of peace.

He tells the crowd his group has "turned the page of violence, forever and with no return."

Islamic Jihad, along with militant group Gamaa Islamiyah, were formed in response to the Muslim Brotherhood's rejection of violence in the 1970s. Their aim was to topple the Egyptian government who they say failed to improve the lives of Egyptian people, and betrayed the country by signing a peace treaty with Israel, the latter the justification for Mr. Sadat's killing.

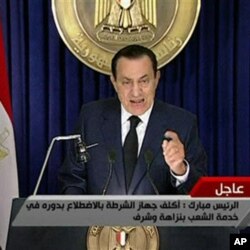

In 1995, the two groups failed in their attempt to kill President Hosni Mubarak. Mr. Mubarak escaped unharmed and retaliated with a massive and ruthless crackdown on the groups' members and their families.

The movement had become paralyzed as thousands of Islamists were in custody, and thousands more had been cut down by the security forces. Mohamed Essam el din Derbala, a leader of Gamaa Islamiyah and colleague of al-Zomour, explains the militants' about face at this point.

Derbala says the government was able to justify its brutal crackdown on all Islamists because of the violence.

In March of this year, when the new military government released al-Zomour, his anger toward the former president was still evident. When he went on television to apologize for the Sadat assassination, his regret was not for taking a life, rather that it ushered in the Mubarak era.

As for now, both Derbala and al-Zomour stress there are no barriers to Islamists taking an open, peaceful part in Egypt's political life. Al-Zomour says he has no political aspirations, though the crowd in Assyut, once a bastion of Islamic extremism, hail him as a natural leader.

And the evening has definite political overtones. Al-Zomour blames interfaith violence on remnants of the old government, an effort to make good on the chaos that Mr. Mubarak warned would ensue should he resign.

The Islamist says that alleged plot won't work.

He says the uprising that led Mr. Mubarak to step down was the work of all elements of society, Muslims and Christians, "even women."

The last is a rare concession to the role of women in political life. His conservative outlook is seemingly countered by the number of women who turn out to hear him speak, a few dozen compared to several thousand men.

The woman sit separately, on a balcony largely out of sight, with only an obscured view of the stage. What is visible across the rows of men below is a banner of Osama bin Laden. Asked why a personification of religious intolerance is being honored at the rally, Gamaa Islamiya's Derbala says it is a coincidence of timing.

Derbala says the group disagreed with bin Laden's methods, but praised him for his fight against the Soviets and later the Americans in Afghanistan. His legacy, he says, must be taken as a whole.

How deeply this brand of Islamism runs is hard to gauge.

Al-Zomour was imprisoned in 1981. Assyut, for one, has changed. Mr. Mubarak sought to counter the poverty that helped breed militancy with infrastructure and industry. And to some extent it seems to have worked. More importantly, Egypt has evolved, with this year's popular uprising showing, as al-Zomour acknowledges, other paths to change.

Some dismiss al-Zomour as a remnant of Egypt's past, unwilling to forget the murder of President Sadat. Others are more forgiving. Meena Hanna, the deputy of the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchy in Assyut acknowledges al-Zomour's message and principles.

He says we respect the principles of every human being, adding, so long as that person respects our principles and our beliefs.

As for whether al-Zomour's professed devotion to tolerance can be taken at face value, the priest is more cautious.

Change is proven by action and reality, he says, not talk and words.