UNITED NATIONS —

As the United States and Russia discuss a possible diplomatic route for Syria to give up its chemical weapons, the matter ultimately may land at the U.N. Security Council. Consensus may be difficult for a Council that has been deeply divided over the Syrian conflict.

The five powers on the 15-nation Council have been unable to agree to any action on Syria's civil war for more than two years, with three resolutions having been vetoed by Russia and China.

Security Council president for September, Australian Ambassador Gary Quinlan, said discussions between the U.S. secretary of state and his Russian counterpart this week in Geneva are very important for ending the Council’s paralysis.

“We all know that the stalemate on Syria has been within the P5 - the permanent members of the Council. We need to break the stalemate, and in order to break it, obviously these kinds of discussions that are under way are necessary, are essential in fact, to bring the sides closer together and to see if we do have a viable, enforceable basis, in fact, for having a solution in respect of Syria’s chemical weapons programs,” said Quinlan.

Clouds on horizon

There already are signs there, however, of difficulty ahead in the Security Council. Russia has said it will not accept a U.N. resolution that references the U.N. Charter's Chapter 7, which allows the use of force, if Syria does not comply. Quinlan said Russia also has indicated it has an alternative text that it may present.

Richard Gowan of New York University’s Center on International Cooperation says he thinks the U.S. will accept a resolution without a Chapter 7 reference only if Russia provides very concrete guarantees that it will make the process work.

“I imagine the Western powers will accept a relatively weak resolution at this time in the expectation that if [Syria's President Bashar] Assad does not play fair, they can come back and table a much tougher resolution in a month or two months’ time,” he said.

Carne Ross, a former British diplomat and head of Independent Diplomat, an advisory firm that counts the Syrian National Coalition among its clients, said a Council decision that does not include Chapter 7 would be “meaningless.” He said there must be conditions and consequences.

“There have to be clear commitments, there have to be deadlines, there has to be rigorous monitoring. If these elements are not in there, then I do not see much chance for agreement,” Ross said.

On Thursday, the U.N. confirmed it had received a document from the Syrian government signaling its intention to join the chemical weapons convention.

The Century Foundation’s Jeffrey Laurenti said Syria’s announcement that it is willing to declare its chemical arsenal and sign the Geneva Convention prohibiting use of such weapons could lead to the quick deployment of U.N. inspectors into the country and possibly remove the need for the threat of use of force in a Council resolution.

“This in itself will presumably be sufficient to assure the government does not launch any more chemical weapons attacks,” he said.

Draft resolution underway

The French, British and Americans are drafting a resolution that could be the starting point for negotiations among the five permanent Council members. Their working draft is reported to include language condemning the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian authorities; demanding the government declare within 15 days the locations, amounts and types of items related to chemical warfare; and imposing sanctions on violators.

The draft also is reported to refer the situation in Syria since 2011 to the International Criminal Court.

Gowan said that is one element that is likely to be quickly compromised away.

“It is absolutely clear that the reference to the International Criminal Court is a gambit that has been put there and will fall out very fast," he said. "I think that to be credible, you would need a reference to sanctions or even the use of force as a response to non-compliance by the Syrian regime. But Russia is not going to allow that.”

Analyst Laurenti said that while the immediate U.S. goal is to stop the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian conflict, its greater challenge will be to end the war that has killed more than 100,000 people.

On this, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has been very clear, saying this week that the collective failure to prevent atrocities in Syria will remain a heavy burden on the standing of the United Nations and its member states. He said he hopes the talks on safeguarding Syria’s chemical weapons will lead to the Security Council playing an effective role in promoting an end to the Syrian tragedy.

The five powers on the 15-nation Council have been unable to agree to any action on Syria's civil war for more than two years, with three resolutions having been vetoed by Russia and China.

Security Council president for September, Australian Ambassador Gary Quinlan, said discussions between the U.S. secretary of state and his Russian counterpart this week in Geneva are very important for ending the Council’s paralysis.

“We all know that the stalemate on Syria has been within the P5 - the permanent members of the Council. We need to break the stalemate, and in order to break it, obviously these kinds of discussions that are under way are necessary, are essential in fact, to bring the sides closer together and to see if we do have a viable, enforceable basis, in fact, for having a solution in respect of Syria’s chemical weapons programs,” said Quinlan.

Clouds on horizon

There already are signs there, however, of difficulty ahead in the Security Council. Russia has said it will not accept a U.N. resolution that references the U.N. Charter's Chapter 7, which allows the use of force, if Syria does not comply. Quinlan said Russia also has indicated it has an alternative text that it may present.

Richard Gowan of New York University’s Center on International Cooperation says he thinks the U.S. will accept a resolution without a Chapter 7 reference only if Russia provides very concrete guarantees that it will make the process work.

“I imagine the Western powers will accept a relatively weak resolution at this time in the expectation that if [Syria's President Bashar] Assad does not play fair, they can come back and table a much tougher resolution in a month or two months’ time,” he said.

Carne Ross, a former British diplomat and head of Independent Diplomat, an advisory firm that counts the Syrian National Coalition among its clients, said a Council decision that does not include Chapter 7 would be “meaningless.” He said there must be conditions and consequences.

“There have to be clear commitments, there have to be deadlines, there has to be rigorous monitoring. If these elements are not in there, then I do not see much chance for agreement,” Ross said.

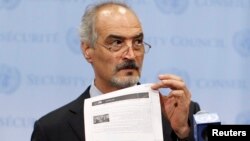

On Thursday, the U.N. confirmed it had received a document from the Syrian government signaling its intention to join the chemical weapons convention.

The Century Foundation’s Jeffrey Laurenti said Syria’s announcement that it is willing to declare its chemical arsenal and sign the Geneva Convention prohibiting use of such weapons could lead to the quick deployment of U.N. inspectors into the country and possibly remove the need for the threat of use of force in a Council resolution.

“This in itself will presumably be sufficient to assure the government does not launch any more chemical weapons attacks,” he said.

Draft resolution underway

The French, British and Americans are drafting a resolution that could be the starting point for negotiations among the five permanent Council members. Their working draft is reported to include language condemning the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian authorities; demanding the government declare within 15 days the locations, amounts and types of items related to chemical warfare; and imposing sanctions on violators.

The draft also is reported to refer the situation in Syria since 2011 to the International Criminal Court.

Gowan said that is one element that is likely to be quickly compromised away.

“It is absolutely clear that the reference to the International Criminal Court is a gambit that has been put there and will fall out very fast," he said. "I think that to be credible, you would need a reference to sanctions or even the use of force as a response to non-compliance by the Syrian regime. But Russia is not going to allow that.”

Analyst Laurenti said that while the immediate U.S. goal is to stop the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian conflict, its greater challenge will be to end the war that has killed more than 100,000 people.

On this, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has been very clear, saying this week that the collective failure to prevent atrocities in Syria will remain a heavy burden on the standing of the United Nations and its member states. He said he hopes the talks on safeguarding Syria’s chemical weapons will lead to the Security Council playing an effective role in promoting an end to the Syrian tragedy.