A French journalist is leaving China after being denied press credentials and facing heavy criticism from the Foreign Ministry and state media over her reporting.

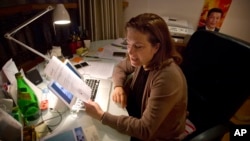

Ursula Gauthier, a longtime journalist for the French news magazine L'Obs, planned to board a flight out of Beijing shortly after midnight on Friday.

She would be the first foreign journalist forced to leave China since 2012, when American Melissa Chan, then working for Al Jazeera in Beijing, was expelled.

The Chinese government refused to renew Gauthier's press credentials, without which she could not obtain a new visa. It demanded that she apologize and express contrition over what it called anti-Chinese bias.

Foreign Ministry spokesmen Lu Kang said Monday that Gauthier was no longer "suitable" to be allowed to work in China because she had supported "terrorism and cruel acts" that killed civilians and refused to apologize for her words.

Gauthier denied she had written anything that could be so interpreted, calling the accusations absurd and saying that China should prosecute her if it truly believed she supported terrorism.

The French foreign ministry issued a statement of regret over China's refusal to renew her visa, while the Foreign Correspondents' Club of China said it was "appalled" by the decision and expressed concern that the government was using the accreditation and visa process to threaten foreign journalists.

Gauthier was also subject to a harsh media campaign for writing in a Nov. 18 article, shortly after the attacks in Paris, that Beijing's expression of solidarity with Paris was partially a bid to gain international support for its contention that ethnic violence in China's northwestern Muslim region of Xinjiang is linked to global terrorism.

Gauthier wrote that some violent attacks in Xinjiang involving members of the minority Uighur community showed no evidence of foreign links — an observation that has been made by other China-based journalists, along with numerous foreign experts on security and on Xinjiang's ethnic policies and practices.

Advocacy groups have argued that the violence is more likely to be a response to Beijing's heavy-handed rule, mass migration by Chinese from other parts of the country to the region, and restrictions on Uighur religious and cultural life.

A Xinjiang court last year sentenced a Uighur scholar critical of China's ethnic policies in Xinjiang to life in prison. In December, a Beijing court convicted a prominent lawyer of fanning ethnic hatred based on his comments that Beijing should rethink its Xinjiang policies.

In her article, Gauthier focused on a recent deadly attack in a mine in Xinjiang portrayed by China as an act of terrorism committed with the collusion of overseas groups.

She described it as more likely an act by Uighurs against mine workers from China's majority Han ethnic group over what the Uighurs perceived as mistreatment, injustice and exploitation.