China’s top legislature passed the nation’s first anti-terrorism law Sunday, which expands the government’s ability to force foreign technology firms to comply with government investigations and could further erode individual rights.

Chinese authorities say the measures will expand abilities to fight terrorism at home and overseas while ensuring protections for individuals and businesses. Beijing insists the law, which goes into effect in January, is necessary and in line with international norms.

Critics of the law when it was drafted included human rights groups and U.S. authorities who said it was overly broad and may threaten freedom of expression and religion as well as intellectual property rights.

Broader powers for Beijing

Chinese officials insist they have struck a balance between heightened measures to battle terrorism and the protection of human rights as well as business interests.

Li Shouwei of the legislature’s criminal law office told a media briefing on Sunday that it will not affect the normal business operations of companies operating in China.

"We do not use the law to set up 'back doors' to violate the intellectual property rights of companies, or to undermine free speech on the Internet and people's religious beliefs."

Critics have argued the opposite, saying that it requires companies to help Chinese authorities decrypt data for counter-terrorism efforts.

Many have questioned why authorities in China, who already possess broad latitude to investigate and detain those suspected of crimes, need expanded powers. Chinese officials say they are dealing with an increase in terrorism.

More curbs on media

But the country’s own definition of terrorism is seen by many as overtly political.

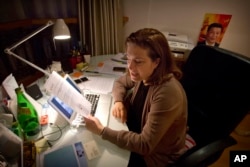

China’s foreign affairs ministry on Saturday, decided to expel French reporter Ursula Gauthier for a story she wrote about ethnic violence in Xinjiang, western China, for the French Weekly L’Obs.

In her article, dated November 18, Gauthier argued that a series of attacks, carried out by members of the Muslim Uighur minority, were a result of China’s own hard-handed policies toward the Uighurs — and not, as the government argues, purely terrorism. The government said it considered that view sympathetic to terrorism, and declined to renew her journalist visa.

Calling the ministry’s move to expel her “absurd,” Gauthier said that the new law will no doubt further suppress free speech in China, which has already been stifled.

“It’s a very wide-reaching law and the part which interests us journalists is that anything that you say or write, which seems to be encouraging terrorism [in China’s eyes], would be illegal,” said the journalist, who will be forced to leave China after her visa expires on December 31.

China’s Xinhua news agency Monday said the new anti-terrorism law will impose additional restrictions on media reporting on domestic terrorism, although it did not give specifics.

Human rights groups have long expressed fears that the law will provide a legal footing for Chinese authorities to further tighten censorship or jail extremists of social movements.

It also allows the People’s Liberation Army to take part in counter-terrorism operations overseas, which are approved by its own Central Military Commission and the countries involved.

Implications for foreign companies

The law also gives the state broader access to sensitive commercial data. The law’s article 18 stipulates that “telecom operators and internet service providers shall provide technical interfaces, decryption and other technical support and assistance” to security agencies, which are pursuing terrorist activities."

That will add pains to tech companies operating in China, and could have an impact on Chinese companies trying to enter foreign markets.

Kitty Fok, managing director of market intelligence firm IDC China, said the law means many companies will now have to seek Chinese partners in order to comply with the new regulations without leaving the country.

“It is definitely difficult, but it is still such an important market for multinational companies that they can’t walk away,” Fok said.

“So that’s why, in the last six months, we have seen a lot of joint ventures of different parts of partnership set up in China,” she added.

Western technology companies have already clashed with authorities in Britain and the United States over providing greater access to encrypted communications of users. Law enforcement officials have argued that tough encryption hinders their ability to catch terrorists. The companies say any back-door methods to weaken encryption will also be exploited by hackers, making all communications more vulnerable.

Xiong Zhiyong, a professor at China Foreign Affairs University who specializes Sino-U.S. relations, argued that more time should be given to see how China enforces the law.

“The law itself is incontestable. But while enforcing the law, the key is whether it will be wrongly applied in areas it shouldn’t be applied to the extent that it overreaches its scope,” Xiong said.

The counterterrorism law is just the latest expansion of Chinese authorities powers under President Xi Jinping. Under President Xi, Chinese officials have exercised greater control over the economy, cracked down on lawyers championing individual rights, and increased a security crackdown in ethnic minority areas such as Tibet and Xinjiang.