Political leaders in water-starved Southern California are headed for a confrontation over an innovative but costly plan to build one of the world’s largest systems for recycling wastewater, VOA has learned.

San Diego officials are casting serious doubt on the proposal, which advocates say could provide the region with a secure source of drinking water even in the event of future droughts or an earthquake.

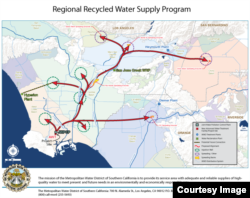

The Metropolitan Water District, Southern California’s massive water importer serving a six-county area and nearly 19 million people, partnered with the Sanitation Districts of Los Angeles County to develop the plan.

By 2035, the project would purify up to 168,000 acre-feet (207 billion liters) of treated wastewater discharged each year into the Pacific Ocean and inject it into local groundwater basins before being pumped out and used as potable water.

According to a still unpublished report obtained by VOA, Metropolitan’s Regional Recycled Water Supply Program has a budget of more than $3.45 billion and projected operating costs of $2,300 per-acre-foot.

“Those [operating] costs are about the same as the Carlsbad desalination plant [about to go online near San Diego] and significantly higher than wholesale imported water at $1,000 an acre-foot,” said Keith Lewinger, an MWD board member representing San Diego County.

San Diego officials doubt a viable market for the extra water exists and question the motives of Metropolitan, the largest distributor of treated drinking water in the United States.

“They’re going to into this with eyes wide shut and wallets wide open with the goal of expanding Metropolitan’s mission when every one of their member agencies are reducing their purchases [of MWD water],” said Dennis Cushman, assistant general manager of the San Diego County Water Authority.

The dispute is the latest chapter in a contentious, decades-long feud between the Water Authority and Metropolitan over San Diego’s longstanding contention that it pays exorbitant fees for water.

A San Francisco Superior Court judge agreed earlier this year, ordering MWD to pay the Water Authority $231.7 million in damages for illegal rates Metropolitan charged from 2011 to 2014. MWD plans to appeal.

Away from imported water

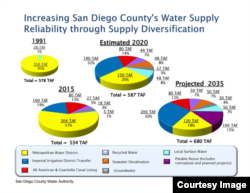

In 1991, the San Diego region was 95 percent reliant on imported MWD water brought in via aqueducts from Northern California and the Colorado River.

By 2020, that will drop to 26 percent as San Diego develops new local and imported supplies.

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti has directed the L.A. Department of Water and Power to slash its purchases of imported water in half by 2025.

“San Diego and L.A. are two of Met’s top buyers,” said Cushman. “Eighty-five percent of their revenue comes from water sales, and those sales have been declining.”

Metropolitan officials contend the project is not only needed locally, but sets the tone for diversifying urban water supply systems throughout the western U.S.

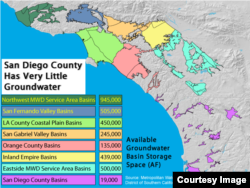

“The purified water produced by this program would represent a new drought-proof supply to help replenish the region’s groundwater basins, which typically produce about a third of Southern California’s overall water needs,” Metropolitan board Chairman Randy Record said last month.

But San Diego’s scant groundwater aquifers provide a mere 19,000 acre-feet (23 billion liters) of storage capacity versus nearly 1.2 million acre-feet (1.5 trillion liters) for L.A. County.

MWD’s solution would make more imported water available for the San Diego authority to purchase as the project’s advanced treated water supplements regional supplies.

“Given our own diversification efforts, its preposterous [for them] to think our region would benefit from this program,” Cushman countered. “San Diego is buying and plans to buy less water from Met, not more.”

Still, experts cautioned against dismissing a project that would assist Southern California’s move away from imported water.

“With climate change here and more severe droughts on the horizon, we’re going to need reserve water from other sources,” said Stanford University’s Richard Luthy. “You’re banking water for future droughts so you can even out fluctuations in rainfall and snowfall.”

But there’s another rub.

The San Diego authority is obligated to buy Carlsbad’s entire output of product water for 30 years through a purchase agreement with Poseidon Water, the Boston-based company that built the plant.

Similar deals between MWD, its member agencies and groundwater basin managers in the project’s target area have yet to be worked out – potentially putting Metropolitan at risk, the report warns.

Billions of dollars…

That worries Lewinger, along with the project’s potentially high operating costs.

“If it’s raining cats and dogs, why would agencies buy expensive water from Met when they’re getting it from the sky?” he asked.

MWD Assistant General Manager Debra Man said those deals will be discussed as a $15 million demonstration plant and feasibility studies approved last month are rolled out in 2016.

Metropolitan officials also provided VOA with official correspondence stating that the cost estimates in the draft report were “based on very conservative assumptions which are now outdated.”

“It’s in the range of $1,700 per-acre-foot and we’re hoping to drive that down even more,” Man said.

MWD has conducted two studies over the past five years on the project, including a $1 million evaluation by the highly regarded engineering firm CDM Smith.

“We'd like to understand what’s changed since those studies were done that would drive down capital and per-acre-foot water costs, and what data and engineering studies will support the statement that costs will be so much lower," Cushman said.

…and miles of pipe

Regardless of the final numbers, the project will shoulder huge distribution costs.

Much of those cover hundreds of kilometers of pipeline and approximately 80 new injection and extraction wells, according to the report.

“MWD will have to get the purified water from our Joint Water Pollution Control Plant in Carson to groundwater basins located all over the L.A. metropolitan area and [neighboring] Orange County,” said Robert Ferrante, the Sanitation Districts’ assistant chief engineer.

Orange County’s water and sanitation districts have run their own Groundwater Replenishment System – currently the world’s largest – since 2008.

The MWD system would be technically similar – forcing wastewater through the same reverse osmosis membranes also used for desalination – but much greater in scale.

Both programs utilize so-called indirect potable reuse – where purified wastewater moves through a groundwater aquifer buffer before reaching those who drink it.

“IPR costs are significant because the water needs to be conveyed to a location and percolated or injected into the ground,” Ferrante said.

San Diego officials welcomed the idea, but questioned whether Metropolitan was the right agency for the job.

“For us the biggest risk is that MWD has zero experience building, owning and operating a recycling plant and potable reuse project,” Cushman said. “It’s an expansion of Met’s mission that’s well outside its wheelhouse.”

But water experts say recycling into urban aquifers must move forward.

“If a big earthquake hits north of L.A. and disrupts flow in the aqueducts, having extra water in the ground is critically important, said Luthy, who directs the National Science Foundation’s Engineering Research Center for re-inventing the nation’s urban water infrastructure.

“Met can’t be the same agency in the 21st century that it was in the 20th,” he said.

This is the first article in a 2-part series on how California is reshaping its urban water supply systems in the face of the state's epic drought. Click here for Part 2.