As California endures a fourth year of punishing drought, state officials are looking to arid Australia for innovative ideas to tackle its water problems.

Much like California, Australia was strapped for cash when it faced a megadrought, its worst-ever recorded, stretching across the 2000s.

Yet by the time the “Millennium Drought” was over, the government had transformed its water management system into one of the most efficient in the world.

The key reform used a cap and trade policy similar to those that have reduced greenhouse-gas emissions in many developed countries.

“The government didn’t have enough money to build more infrastructure, so it developed a cap and trade system,” said Giulio Boccaletti, who heads the U.S.-based Nature Conservancy's Global Freshwater Program.

Upgrades such as drip and computerized irrigation and aqueduct lining were built into the system and paired with urban conservation techniques such as stormwater capture and recycling.

Greywater systems were introduced that recycle shower and washing machine water to irrigate gardens. Sprinkler use on lawns was banned.

“Their programs have reduced the average household daily water use to 55 gallons per person, compared to an average of 140 gallons in California between 2001 and 2010,” said Heather Cooley of the Oakland, California-based Pacific Institute, a non-profit environmental research group.

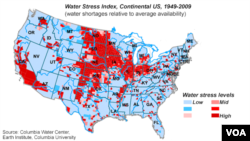

The reforms are catching the attention of water managers throughout the American West, 35 percent of which is in severe drought.

“They’ve done a lot of things we’ve been looking at as a model,” said California’s top water regulator, Felicia Marcus, who heads the state’s Water Resources Control Board.

Australia’s water markets

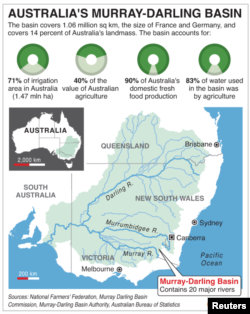

Australia’s water revolution started with agriculture, which dominates consumption, as in similarly drought-prone California.

Rather than slash the water rights long held by farmers and other irrigators, the government ran a $2.4 billion buyback program to purchase water for the environment, coupled with a $4.5 billion infrastructure program.

Overall use was capped.

“The most significant thing we did was embrace a better water rights system designed to ensure the transition to efficient water use and innovation,” said Mike Young, a professor at the University of Adelaide.

Restrictions on Australia’s water trade, in place since the late 1980s, were gradually eliminated. A national online marketplace now does nearly $2 billion in business each year.

“We basically copied the banks,” said Young, who received a national award for his role in developing improved water entitlement, allocation and trading systems in Australia and is now in the U.S. working on a similar blueprint.

“If you want to sell water to me and we’re in the same hydrographic area, just log in and transfer the shares from your account to mine,” he said.

At the peak of the drought, nearly all of Australia’s rice growers and many dairy farmers — both are in highly water intense forms of agriculture — scaled back production and sold water at high prices to citrus and grape growers.

“The market facilitated a reallocation of water from low value to higher value use,” Boccaletti said.

Getting to that point was not easy.

Australia spent a decade measuring withdrawals from its major rivers before amassing enough data to move to a free market system.

California, where many irrigators still lack water meters, faces similar challenges.

“We don’t have that data yet,” Marcus said. “We’re focusing on [collecting it] so we have the option to use [market-based] water transfers to much greater extent than we can today.”

Another hurdle for California is sorting out competing claims among rights holders, some of which date back more than a century.

That’s difficult when most river systems in the state are not adjudicated.

With regulators emboldened by emergency drought legislation, tougher metering requirements are on the horizon.

California’s arcane water laws…

California is saddled with the most complex water rights system in the U.S. – a set of Gold Rush-era laws originally designed to protect the prospectors who panned the streams of the Sierra Nevada.

The arrangement is obsolete and inefficient, water policy experts say.

Like in most Western states, California water law grants those with the earliest claims legal priority to surface water, which becomes scarce during droughts.

But the regulations discourage conservation.

“It’s a use-or-lose system that prevents more economically efficient water use,” said Upmanu Lall, a leading hydroclimatology expert who heads Columbia University’s Water Center.

In Australia, state governments “allocate” surface water to irrigators throughout the year. The percentage depends on seasonal availability, and “shareholders” can either sell their allocation or trade parts of it away.

That kind of flexibility is impossible in California.

“If your water rights are for mining or agriculture and you lease them to someone in another industry you may lose them, since they’re tied to a specific, beneficial use,” Lall said.

California has had water trading for years, but activity is limited and the system more akin to in-person bartering than Australia’s computerized, highly efficient marketplace.

“A real concern is that we don’t know how much water is traded — formally or informally — because no one is tracking it,” Cooley said.

On top of that, lawyers have already filed four lawsuits with multiple claims challenging last month’s announced cutbacks in surface water allocations for more than 100 senior rights holders in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta and watersheds.

“This is our water. We believe firmly in that fact, and we are willing to take on the state bureaucracy to protect that right,” said Steve Knell, general manager of the Oakdale Irrigation District, in a statement.

Many of those with more junior rights, whose allocations have already been slashed, are being hit hard, forcing them to fallow thousands of acres of cropland.

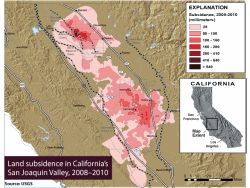

Others are pumping groundwater at alarming rates.

As a result, parts of California’s San Joaquin Valley — America’s most productive farmland — are sinking by more than 30 cm per year, according to U.S. Geological Survey data.

“Right now the state has only about one year of water supply left in its reservoirs, and our strategic backup supply, groundwater, is rapidly disappearing,” wrote NASA’s Jay Famiglietti earlier this year.

State lawmakers finally passed groundwater pumping restrictions in 2014, last in the American West to do so. But water agencies in California’s most over-pumped basins are not required to submit their plans until 2020, with sustainability targets pushed out until 2040.

…And skyrocketing costs

Australia’s 22 million inhabitants are mostly concentrated along the country’s southeastern coast, close to their water sources and serviced by a handful of integrated water management systems.

In contrast, most of California’s nearly 39 million people live in large urban areas hundreds of kilometers away from their water sources — often a disparate mix that the state’s 3,000 wholesalers and retailers cobble together.

The State Water Project, one of the largest public water, power and conveyance systems in the world, includes some 22 dams and reservoirs and a 700-kilometer-long aqueduct that carries water from the Delta through the Central Valley to Southern California.

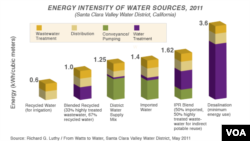

Getting that water into the Los Angeles basin requires it to be pumped more than 610 meters over the Tehachapi Mountains — the highest single water lift in the world.

“The energy use for the pumping transfer project is enormous — roughly equivalent to modern desalination,” Lall said.

The Colorado River also supplies California, which is entitled to about 5.4 billion cubic meters of its water per year, diverted through nearly 400 kilometers of aqueducts and tunnels, to Southern California.

While most of it goes to agriculture, the Colorado remains a vital source for a string of Western cities including Los Angeles and San Diego.

“Until now, many California water utilities have prided themselves on doing such a good job obtaining water from far away, getting it to people safely, that they could take it for granted,” Marcus said.

“We need to do a massive amount of water education for folks to understand their water system the way [they do] in Australia,” she said. “They’ve put millions of dollars into that. They also have a fraction of the number of water agencies that we do.”

Change is hard

After having over-allocated its primary river system, the Murray-Darling, for decades, things began to turn around for Australia in 2004 when the country’s federal, state and territory governments agreed to jointly manage their water policy.

After years of investment, scientists now use thousands of newly installed gauges to measure rainfall and surface water, while groundwater is monitored in 800,000 bore locations. The information enables regulators to maintain ecosystems while more precisely capping diversions from rivers and streams.

And that’s just the beginning.

“They retrofitted their cities using green infrastructure — much as Los Angeles has great plans for — by capturing rainwater when it falls in urban watersheds,” Marcus said. “They spent millions, maybe billions, building expensive systems underneath their parks and cities to capture water.”

A hugely controversial step was investing more than $12 billion to build six desalination plants, four of which were shut down in 2012 when the drought ended — the plants are more expensive to run than to use the green infrastructure they’d created.

These debates are already evident in California, where a $1 billion desalination facility — the largest in the Western hemisphere — is scheduled to go online this year in Carlsbad, north of San Diego.

California Governor Jerry Brown is also under fire, fighting off criticism after his April 1 announcement exempting farmers from 25 percent cuts in urban water use — the first mandatory drought restrictions in state history.

To reach that target, communities with the highest per capita usage were required to cut up to 36 percent; others, like San Francisco and Redwood City, where conservation is strong, just eight percent.

The city of Riverside, east of Los Angeles, is suing California, claiming its 28 percent restrictions unfairly impact the community. The state board is preparing for more such litigation.

Marcus remains unfazed.

“The changes we’re going to make in conservation, recycling, stormwater capture and in [effecting] appropriate desalination, is something we need and won’t regret in the future,” she said.