For many Egyptians, Hussien Salem is a symbol of everything wrong with their old regime.

A close friend of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, the businessman-turned-fugitive allegedly made millions off favorable deals thanks to his connections with the former regime. He now sits under house arrest in Spain, likely to be tried in absentia if Egypt’s request for extradition isn’t granted.

It was inequities like this special brand of crony capitalism that motivated many to take to the streets in 2011 asking for “Bread, Freedom and Social Justice”.

Political and economic corruption was a key grievance for Arab Spring protestors, but overthrowing their long time leaders has not been enough for them to gain faith in their new governments that continue to struggle with the former economic systems.

Despite ending three decades of Mubarak’s rule, according to a report released today by Transparency International, many in Egypt still perceive the country as corrupt. The same can be said for Tunisia, Libya and Yemen.

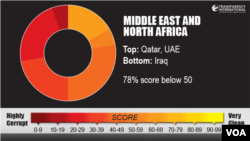

Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perception Index ranks 176 countries and territories based on interviews with businessmen, local and foreign investors and others who interact with the public sector. Most of the Arab Spring states still rank in the bottom half.

Moammar Gadhafi, who ruled Libya for over 40 years, was legendary for misallocating public resources and spending significant oil revenues on buying weapons and sponsoring rebels groups aboard. The uprising overthrew the Gadhafi regime and cost thousands of lives, but left Libya remains near the bottom of the index at 160 out of 176 states.

While it’s a slight improvement from last year, Arwa Hassan, Transparency International’s Middle East and North Africa outreach manager, said Libya is not alone. Few Arab countries saw significant improvement.

“The general trend is that some countries have improved slightly, but some have deteriorated significantly,” Hassan said. “It does give an indication that there are still serious problems and lots of work needs to be done.”

Tunisia dropped slightly after being the first country to oust their leader in what became the Arab Spring. Bahrain also dropped just slightly from 48 in 2010 to 53 this year after failing to achieve significant changes through their months of continued crackdown on anti-government protests.

Egypt dropped significantly—from 98 in 2010 to 118 in 2012.

Hassan said that while this may seem disappointing, it could be the post-uprising changes are slow to happen in the Arab world.

“One would expect to see some kind of improvement but it can take a while before changes take effect,” Hassan said. “What will be very interesting will be next year[‘s] index and then we will really see if there are changes.”

Today the gap between the rich and poor in the Arab world remains wide.

In Egypt, international institutions like the World Bank are warning of a possible continued economic downturn.

Magda Kandil, executive director of the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies, said the lack of government regulation in Egypt allowed corruption to prevail and the fruits of growth to fall into the hands of a few.

“The economy at large was growing, but it was not trickling down," Kandil said of the Mubarak era. She said it was because of this endemic "crony capitalism" that liberalization policies had such destructive effects in the country.

But some in Egypt say the situation has actually worsened and the laws that benefited connected businessmen like Salem, and allowed regular Egyptians to be extorted by officials, are being used by new leaders.

A key problem, said Mohamed El-Sawy, head of the Anti-Corruption Task Force at the Egyptian Junior Business Association, are laws that govern licensing and procurement are conflicting and unclear. He said there will often be several conflicting laws that govern even a single transaction.

“For example, once an investor was building a mall,” he said. “First he was told you need one story of parking. He goes back and another clerk says ‘A whole story of park? That is too much.’ He goes again and third clerk says, ‘No, you should have no parking’ and they are all legal.”

The culture of bribes is strong in Egypt and extortion is easier when laws are unclear as government reform lags. “The current regime is taking advantage of Mubarak’s system to take more power,” El-Sawy said.

The tracks of land sold off below market value to connected businessmen like Salem became sources of revenue for the rich rather than a breadbasket for Egypt’s poor.

“We need checks and balances,” El-Sawy said. “We need to take a step back and design a five to 10-year plan."

A close friend of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, the businessman-turned-fugitive allegedly made millions off favorable deals thanks to his connections with the former regime. He now sits under house arrest in Spain, likely to be tried in absentia if Egypt’s request for extradition isn’t granted.

It was inequities like this special brand of crony capitalism that motivated many to take to the streets in 2011 asking for “Bread, Freedom and Social Justice”.

Political and economic corruption was a key grievance for Arab Spring protestors, but overthrowing their long time leaders has not been enough for them to gain faith in their new governments that continue to struggle with the former economic systems.

Despite ending three decades of Mubarak’s rule, according to a report released today by Transparency International, many in Egypt still perceive the country as corrupt. The same can be said for Tunisia, Libya and Yemen.

Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perception Index ranks 176 countries and territories based on interviews with businessmen, local and foreign investors and others who interact with the public sector. Most of the Arab Spring states still rank in the bottom half.

Moammar Gadhafi, who ruled Libya for over 40 years, was legendary for misallocating public resources and spending significant oil revenues on buying weapons and sponsoring rebels groups aboard. The uprising overthrew the Gadhafi regime and cost thousands of lives, but left Libya remains near the bottom of the index at 160 out of 176 states.

While it’s a slight improvement from last year, Arwa Hassan, Transparency International’s Middle East and North Africa outreach manager, said Libya is not alone. Few Arab countries saw significant improvement.

“The general trend is that some countries have improved slightly, but some have deteriorated significantly,” Hassan said. “It does give an indication that there are still serious problems and lots of work needs to be done.”

Tunisia dropped slightly after being the first country to oust their leader in what became the Arab Spring. Bahrain also dropped just slightly from 48 in 2010 to 53 this year after failing to achieve significant changes through their months of continued crackdown on anti-government protests.

Egypt dropped significantly—from 98 in 2010 to 118 in 2012.

Hassan said that while this may seem disappointing, it could be the post-uprising changes are slow to happen in the Arab world.

“One would expect to see some kind of improvement but it can take a while before changes take effect,” Hassan said. “What will be very interesting will be next year[‘s] index and then we will really see if there are changes.”

Today the gap between the rich and poor in the Arab world remains wide.

In Egypt, international institutions like the World Bank are warning of a possible continued economic downturn.

Magda Kandil, executive director of the Egyptian Center for Economic Studies, said the lack of government regulation in Egypt allowed corruption to prevail and the fruits of growth to fall into the hands of a few.

“The economy at large was growing, but it was not trickling down," Kandil said of the Mubarak era. She said it was because of this endemic "crony capitalism" that liberalization policies had such destructive effects in the country.

But some in Egypt say the situation has actually worsened and the laws that benefited connected businessmen like Salem, and allowed regular Egyptians to be extorted by officials, are being used by new leaders.

A key problem, said Mohamed El-Sawy, head of the Anti-Corruption Task Force at the Egyptian Junior Business Association, are laws that govern licensing and procurement are conflicting and unclear. He said there will often be several conflicting laws that govern even a single transaction.

“For example, once an investor was building a mall,” he said. “First he was told you need one story of parking. He goes back and another clerk says ‘A whole story of park? That is too much.’ He goes again and third clerk says, ‘No, you should have no parking’ and they are all legal.”

The culture of bribes is strong in Egypt and extortion is easier when laws are unclear as government reform lags. “The current regime is taking advantage of Mubarak’s system to take more power,” El-Sawy said.

The tracks of land sold off below market value to connected businessmen like Salem became sources of revenue for the rich rather than a breadbasket for Egypt’s poor.

“We need checks and balances,” El-Sawy said. “We need to take a step back and design a five to 10-year plan."