Jean-Pierre has modest ambitions. "My hope for the future is to work, start a family and lead a very simple life," he said, standing on the patio of a Capurganá hotel restaurant.

The young Haitian man, who did not give his real name for publication, has already spent more than four years in this northwestern Colombia beach community close to Panama's border. "We are treated well here," he said. But he plans to leave someday for his dream destination in the United States.

It's a dream shared by thousands who arrive in Capurganá. Once primarily a tourist destination with a population of 3,000, the town has swollen in recent years with migrants — mostly Haitians, like Jean-Pierre, as well as Cubans, South Americans, Africans, South Asians and others, all aiming for the U.S. or Canada.

From Capurganá, northbound migrants must confront the nearby Darien Gap, a roadless 97-kilometer stretch of dense tropical forest that links South America and Central America. It requires a grueling one- to two-week trek through mountainous terrain. Those who embark on the journey risk hunger, exhaustion, injury and disease, poisonous snakes, and armed criminals.

Many pay "coyotes" to guide them through the jungle. Some are forced by narcotraffickers to carry up to 25 kilos of coca bricks in their backpacks in exchange for passage, General Jorge Luis Vargas, the director of Colombia's police, told a VOA Spanish Service team visiting the area in June.

"They are assaulting and raping," said Alan Queen, a Cuban migrant stranded in Capurganá after two failed attempts to traverse the jungle. "We are trapped because the only way out is the jungle, which is full of dangers."

Trekkers "get robbed, and if they are traveling with women, most of them — they get raped," Raul Lopez, project coordinator of Doctors Without Borders' operations in eastern Panama, said in a phone interview. "It's not only the normal violence, it's the sexual violence. … And it's not only happening with adults, it's happening with minors."

Lopez said migrants also face perilously high rivers during the rainy season, from late April into December, as well as injuries, fever, diarrhea and other health risks. The international medical aid group in May opened a new treatment center in Bajo Chiquito, the first community encountered on the Panama side of the jungle, to provide physical and mental health services to a surging number of arrivals.

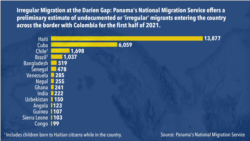

Nearly 27,000 migrants made "irregular," or undocumented, crossings through the Darien Gap into Panama in the first six months of this year, according to preliminary figures from that government's National Migration Service.

That's up from almost 6,500 last year, when COVID-19 restrictions slowed movement globally. Irregular border crossings into Panama had soared from under 7,000 in 2017 to almost 24,000 in 2019.

Entire families, not just single men, are on the move to escape violence and poverty deepened by pandemic job losses, humanitarian groups say. Doctors Without Borders has urged Colombian and Panamanian authorities to ensure migrants' safety. The U.N. Children's Agency has warned that the Darien Gap is too dangerous for youngsters, though more than 4,000 had crossed this year as of late June. The agency has called for more aid.

A State Department spokesperson, in an email response to a VOA query about any U.S. role in the Darien Gap, said the United States works with Panama's government "through international organization and NGO (nongovernmental organization) partners to improve Panama's national asylum capacity; ability to address irregular migration; ability to provide protection and basic humanitarian aid to asylum seekers, refugees, and vulnerable migrants; and promote safe, orderly, and humane alternatives to continuing a journey northward."

Days after the July 7 assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moise and anti-government protests in Cuba, Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas explicitly warned Haitians and Cubans — the most prevalent nationalities at the Darien Gap — against trying to enter the U.S. illegally, especially by sea.

Yet some migrants will not be deterred.

"I don't know how to get to the U.S.," Jean-Pierre said from the Capurganá hotel patio, "but we're all going to hit the road. … In life, you have to take risks for your dreams to materialize."

Funneling through Necoclí

Most migrants approaching the Darien Gap have already taken plenty of risks, having spent months or even years to get that far.

They typically reach Capurganá via a two-hour boat trip from another Colombian port town, Necoclí. The passage can be turbulent in smaller motorboats, with waves sometimes cresting at 10 meters. And while Colombians pay a fare of roughly 3,000 pesos, or about 80 U.S. cents, migrants are charged $50, VOA learned. Migrants also must pay a $20 entry fee to disembark in Capurganá.

As of this week, more than 11,000 foreigners were awaiting boat transportation in Necoclí, whose typical population of 21,000 had swelled to 32,000, Colombia authorities told VOA.

Necoclí is straining to accommodate the stranded arrivals. Food prices have soared and drinking water has become scarce.

"Here we are, suffering, and we have more distance to go. We are thousands, but we only want to pass. … But there are no tickets," Samin Rizcatd, a Haitian migrant, told VOA's Spanish Service.

Necoclí's mayor, Jorge Augusto Tobón Castro, said his town was overwhelmed: "We don't have a single room. There is no food."

Tobón expressed additional concern about overcrowding amid the COVID-19 pandemic and said he had asked Colombia's government "to set up a permanent migration post and allocate resources" to address problems.

Colombia's defense minister, Diego Molano, said the government was seeking immediate talks with Panama to address migratory flows.

Capurganá as staging area

Once they reach Capurganá, migrants can set out on their own, meet up with others or arrange for guides. Several migrants carry young children; and many bring machetes and big plastic bags stuffed with clothing, mats and tents to aid them in the jungle. Possessions litter the jungle routes, abandoned by people too weary to lug them.

Some migrants get no farther than Capurganá. They run out of money and can't pay coyotes to guide them. Or they are frightened by stories of Darien Gap's dangers. Or they try but turn back, exhausted.

Getting beyond the gap

Some never emerge alive from the vast jungle, though the death toll is unclear. Still, migrants continue to stream through the Darien Gap, many with stories or signs of trauma, humanitarian aid workers say.

"They are telling you that they found dead bodies during the walk," said Lopez of Doctors Without Borders.

Though numbers of arriving migrants can vary, "we were receiving 800 people per day" in Darien province in early July, said Diana Maritza Romero Baron, a UNICEF field project manager in Panama.

"Most of them face psychosocial issues," Romero told VOA in an interview.

Especially vulnerable are children and pregnant women, she said. Her organization found that half of the 4,000-plus youngsters arriving so far this year have been younger than 5.

UNICEF estimated that from January through April, more than 200 pregnant women came through the Darien Gap. "Most were in the third trimester — very dangerous," Romero added.

She also noted that a record 62 unaccompanied minors had reached Panama through the Darien Gap this year. Of those, 20 were from Africa. Most were adolescent males.

Romero said some children and families are referred for further medical assistance. Depending on need, doctors at health centers will refer youngsters to Panama's protective services.

Migrants arriving in Panama are registered by authorities and within three days are transferred to migrant reception stations elsewhere in the country, according to Doctors Without Borders. Then they wait for authorization, based on a "controlled flow" agreement between Panama and Costa Rica, to continue through Central America on their own.

Said Romero of UNICEF, "It's important for us … that the children don't cross" the Darien Gap. "It's dangerous, traumatic, so peligroso."

This report originated in VOA's Spanish Service, with reporting by Jair Díaz and David Parra, videography by Oscar Cavadia, photos by David Hernández and field production by Karen Daza. Contributors include VOA State Department correspondent Nike Ching and the Africa Division's Carol Guensburg, Koi Gouahinga and Eddy Isango.