This is Part Two of a five-part series on Renewable Energy for Africa

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

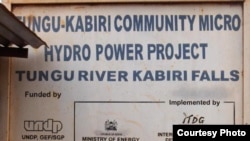

Little more than a decade ago Mbuiru village in Tungu Kabiri district in central Kenya was a “typical African backwater,” said John Kapolon, of the UK-based Practical Action NGO.

The inhabitants of Mbuiru struggled to survive as subsistence farmers. Some of the villagers had skills such as welding and hairdressing they’d learned in the capital, Nairobi, 115 miles to the south. Many of them dreamed of owning their own businesses.

But their desire to develop themselves remained unattainable. Mbuiru’s inhabitants were among the estimated 85 percent of Kenya’s population of 43 million who to this day do not have access to electricity, according to the United Nations.

“I remember visiting the area and people really had a lot of problems. While communications technology was common in the cities, the people of Mbuiru had to walk long distances to find electricity just to charge their cellphones,” Kapolon recalled, adding, “Really, the people at Mbuiru had nothing….”

But they did have a stream that wound its way down the slopes of Mount Kenya past their settlement. It proved to be perfect for a unique project that has transformed Mbuiru into an example of achievement in an otherwise impoverished, neglected district.

Ideal site

Clean power experts from Practical Action visited Mbuiru for the first time in 1999. “We immediately saw that it had a strong stream that could be used to generate electricity,” said Kapolon, a renewable energy project officer for the NGO.

To be sure that a power generation scheme was sustainable at the village, the NGO employed experts to analyze the River Tungu’s flow records going back 40 years. The data showed that even during times of drought the stream at Mbuiru had never stopped running as it is constantly fed by ice melts and precipitation from nearby Mount Kenya. It was ideal for a micro-hydropower project, said Kapolon.

The Tungu Kabiri project harnesses energy from falling water. A weir collects the water, which is then diverted through a concrete canal into a large tank. Water released from the tank goes down a pipeline into a powerhouse containing a turbine and a generator. Energy from the water turns the turbine, which then drives the generator to produce electricity.

The community helped build the project. “All the manual labor and a bit of skilled labor, it all came from the community. What Practical Action did was to provide technical support in terms of designing the system and also supervising the construction, and also supplying a turbine and a generator,” said Kapolon.

The NGO taught locals to maintain the micro-hydropower system.

Pioneering clean power project

The venture at Mbuiru is the first of its kind in East Africa and is providing a blueprint to governments in the region for water-saving and renewable energy.

“Once the turbine turns from the running water, you divert the water back to the stream so you don’t waste water,” said Kapolon. “The big advantages of a micro-hydro plan are that you use little water to produce power, and it’s cheap when compared to other electricity schemes. It’s not very cost intensive because you are not putting up huge structures. You can generate power for one household with very little cost.”

Kapolon said the Tungu Kabiri project is capable of generating 14 Kw [kilowatts] of electricity every 24 hours. It cost about $3,500 per installed Kw, so the project cost about $49,000 to implement. In contrast, it costs Kenya more than $30,000 per Kw installed by means of conventional hydropower.

The Kenya Power company confirmed that about 60 per cent of the total electricity generated in Kenya is by hydropower, making conventional electricity extremely expensive.

Kapolon said the project at Mbuiru doesn’t directly electrify individual houses, but rather provides power to a business centre. There, the electricity charges lead acid batteries, similar to those used in cars, owned by individual households.

“You charge that battery for…six hours to seven hours. The individual owner of the battery will take it home. Then they can use it [for power] for a number of days, up to four or five days, before returning it back for charging,” Kapolon explained. “At the charging station, householders must pay a little amount, less than a dollar a time, for charging, so it’s very economical and people pay very little for electricity when compared with people living in Nairobi.”

The project benefits 200 households [around 1,000 people] in Mbuiru village.

Micro-hydro boon

Kapolon said perhaps the project’s greatest achievement has been a rise in recent years of educated people emerging from the area.

“Children are using the light to study at night. When we started the first phase of this project in 1999, there were no university graduates from this part of the world. There were not even any high school graduates,” he said. “But we have seen over a number of years now, over ten years, we’ve seen the number of graduates increasing. (Local) people are attributing this to the presence of electricity.”

Computers, such an essential part of modern education and enterprise, are also now fixtures at Mbuiru. “The electricity powers a business center, where people are able to use computers for the first time in their lives. They now use the Internet to check on the latest prices for their agricultural produce, so they know the best prices they can get for their goods at market.”

Kapolon said agribusinesses are now flourishing in the village. “They can produce products that are required in the market. They know exactly what is needed in the market, by using the Internet.”

Electricity has also made it possible to establish grain mills and refrigeration enterprises for local food producers. “Some of these foodstuffs are perishable, so putting up deep freezers and fridges was very beneficial to the people who were producing perishable goods,” said Kapolon.

Farmers now sell more products as food that previously rotted is cold-stored, preserved and taken for sale when the market needs it.

Kapolon added, “We also now have businesses [at Mbuiru] that process oil. Some of the villagers grow oil crops, like sunflowers, and they now use electrical equipment to process the oil.”

Power has given villagers entry into the tobacco industry and an assortment of other businesses. “They use the electricity for drying of the tobacco. Currently they have opened a number of enterprises – small ones, like welding, battery charging, hair salons and mobile [phone] charging stations. They are attributing these benefits to the coming of electricity.”

Electricity from the micro-hydropower project now also drives pumps that channel water directly to the community, saving the villagers a lot of time and effort. “Getting water was a big challenge previously. They would have to visit the river all the time for water, carrying it manually in jerry cans or buckets,” said Kapolon.

Environmental impact

Despite the advantages of micro-hydropower, it has its critics. They say it harms the environment by slowing the flow of rivers and streams.

But Kapolon argued, “If done properly, it doesn’t reduce the amount of water for people. You only divert the water; you don’t harvest it. You return it to the river without any major reduction to the river’s flow. But obviously if you divert large amounts of water, the impact on people will be bad.”

He acknowledged that some micro-hydro operations kill fish when they get trapped in pipes. But Kapolon added, “We work with streams that are so small that they don’t have any fish in them.”

He maintained that correctly installed micro-hydropower projects are environmentally friendly. “They don’t require big dams to be built, which often have terrible environmental and social effects, when the dams stop river flows or cause flooding,” said Kapolon.

He pointed out that such projects largely eliminate the need for people to damage forests through collecting wood for fires. They no longer need to use “dirty fuels,” such as diesel for milling grain and kerosene for lighting.

Kapolon says the government of Kenya is very impressed with the Tungu Kabiri scheme. “The state wants to emulate its success. They want to roll out similar schemes throughout the country, so we are currently looking at various models to make sure that all of these centers will be sustainable.”

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

Little more than a decade ago Mbuiru village in Tungu Kabiri district in central Kenya was a “typical African backwater,” said John Kapolon, of the UK-based Practical Action NGO.

The inhabitants of Mbuiru struggled to survive as subsistence farmers. Some of the villagers had skills such as welding and hairdressing they’d learned in the capital, Nairobi, 115 miles to the south. Many of them dreamed of owning their own businesses.

But their desire to develop themselves remained unattainable. Mbuiru’s inhabitants were among the estimated 85 percent of Kenya’s population of 43 million who to this day do not have access to electricity, according to the United Nations.

“I remember visiting the area and people really had a lot of problems. While communications technology was common in the cities, the people of Mbuiru had to walk long distances to find electricity just to charge their cellphones,” Kapolon recalled, adding, “Really, the people at Mbuiru had nothing….”

But they did have a stream that wound its way down the slopes of Mount Kenya past their settlement. It proved to be perfect for a unique project that has transformed Mbuiru into an example of achievement in an otherwise impoverished, neglected district.

Ideal site

Clean power experts from Practical Action visited Mbuiru for the first time in 1999. “We immediately saw that it had a strong stream that could be used to generate electricity,” said Kapolon, a renewable energy project officer for the NGO.

To be sure that a power generation scheme was sustainable at the village, the NGO employed experts to analyze the River Tungu’s flow records going back 40 years. The data showed that even during times of drought the stream at Mbuiru had never stopped running as it is constantly fed by ice melts and precipitation from nearby Mount Kenya. It was ideal for a micro-hydropower project, said Kapolon.

The Tungu Kabiri project harnesses energy from falling water. A weir collects the water, which is then diverted through a concrete canal into a large tank. Water released from the tank goes down a pipeline into a powerhouse containing a turbine and a generator. Energy from the water turns the turbine, which then drives the generator to produce electricity.

The community helped build the project. “All the manual labor and a bit of skilled labor, it all came from the community. What Practical Action did was to provide technical support in terms of designing the system and also supervising the construction, and also supplying a turbine and a generator,” said Kapolon.

The NGO taught locals to maintain the micro-hydropower system.

Pioneering clean power project

The venture at Mbuiru is the first of its kind in East Africa and is providing a blueprint to governments in the region for water-saving and renewable energy.

“Once the turbine turns from the running water, you divert the water back to the stream so you don’t waste water,” said Kapolon. “The big advantages of a micro-hydro plan are that you use little water to produce power, and it’s cheap when compared to other electricity schemes. It’s not very cost intensive because you are not putting up huge structures. You can generate power for one household with very little cost.”

Kapolon said the Tungu Kabiri project is capable of generating 14 Kw [kilowatts] of electricity every 24 hours. It cost about $3,500 per installed Kw, so the project cost about $49,000 to implement. In contrast, it costs Kenya more than $30,000 per Kw installed by means of conventional hydropower.

The Kenya Power company confirmed that about 60 per cent of the total electricity generated in Kenya is by hydropower, making conventional electricity extremely expensive.

Kapolon said the project at Mbuiru doesn’t directly electrify individual houses, but rather provides power to a business centre. There, the electricity charges lead acid batteries, similar to those used in cars, owned by individual households.

“You charge that battery for…six hours to seven hours. The individual owner of the battery will take it home. Then they can use it [for power] for a number of days, up to four or five days, before returning it back for charging,” Kapolon explained. “At the charging station, householders must pay a little amount, less than a dollar a time, for charging, so it’s very economical and people pay very little for electricity when compared with people living in Nairobi.”

The project benefits 200 households [around 1,000 people] in Mbuiru village.

Micro-hydro boon

Kapolon said perhaps the project’s greatest achievement has been a rise in recent years of educated people emerging from the area.

“Children are using the light to study at night. When we started the first phase of this project in 1999, there were no university graduates from this part of the world. There were not even any high school graduates,” he said. “But we have seen over a number of years now, over ten years, we’ve seen the number of graduates increasing. (Local) people are attributing this to the presence of electricity.”

Computers, such an essential part of modern education and enterprise, are also now fixtures at Mbuiru. “The electricity powers a business center, where people are able to use computers for the first time in their lives. They now use the Internet to check on the latest prices for their agricultural produce, so they know the best prices they can get for their goods at market.”

Kapolon said agribusinesses are now flourishing in the village. “They can produce products that are required in the market. They know exactly what is needed in the market, by using the Internet.”

Electricity has also made it possible to establish grain mills and refrigeration enterprises for local food producers. “Some of these foodstuffs are perishable, so putting up deep freezers and fridges was very beneficial to the people who were producing perishable goods,” said Kapolon.

Farmers now sell more products as food that previously rotted is cold-stored, preserved and taken for sale when the market needs it.

Kapolon added, “We also now have businesses [at Mbuiru] that process oil. Some of the villagers grow oil crops, like sunflowers, and they now use electrical equipment to process the oil.”

Power has given villagers entry into the tobacco industry and an assortment of other businesses. “They use the electricity for drying of the tobacco. Currently they have opened a number of enterprises – small ones, like welding, battery charging, hair salons and mobile [phone] charging stations. They are attributing these benefits to the coming of electricity.”

Electricity from the micro-hydropower project now also drives pumps that channel water directly to the community, saving the villagers a lot of time and effort. “Getting water was a big challenge previously. They would have to visit the river all the time for water, carrying it manually in jerry cans or buckets,” said Kapolon.

Environmental impact

Despite the advantages of micro-hydropower, it has its critics. They say it harms the environment by slowing the flow of rivers and streams.

But Kapolon argued, “If done properly, it doesn’t reduce the amount of water for people. You only divert the water; you don’t harvest it. You return it to the river without any major reduction to the river’s flow. But obviously if you divert large amounts of water, the impact on people will be bad.”

He acknowledged that some micro-hydro operations kill fish when they get trapped in pipes. But Kapolon added, “We work with streams that are so small that they don’t have any fish in them.”

He maintained that correctly installed micro-hydropower projects are environmentally friendly. “They don’t require big dams to be built, which often have terrible environmental and social effects, when the dams stop river flows or cause flooding,” said Kapolon.

He pointed out that such projects largely eliminate the need for people to damage forests through collecting wood for fires. They no longer need to use “dirty fuels,” such as diesel for milling grain and kerosene for lighting.

Kapolon says the government of Kenya is very impressed with the Tungu Kabiri scheme. “The state wants to emulate its success. They want to roll out similar schemes throughout the country, so we are currently looking at various models to make sure that all of these centers will be sustainable.”