At a youthful 1,400 years, Islam, relatively speaking, is one of the world's younger religions — and it's on track to be the world's largest sometime this century.

That's the prediction from demographers at the Pew Research Center who say high fertility rates among Muslim women and a youth bulge in the faith are fueling its growth.

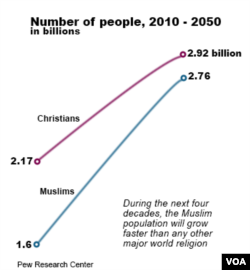

A Pew survey released this month, “The Future of World Religions,” says that if current trends continue, Islam will surpass Christianity in 2070 to become the world’s largest faith.

A panel of demographers discussed the findings of the report recently during a seminar at the headquarters of Pew’s Religion & Public Life project.

Conrad Hackett, the lead researcher on the report, said that while fertility rates around the world are slipping toward the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman, Muslim women are having on average more than three children each. At the same time, around a third of all Muslims are under age 15.

“What this means is that the Muslim population has more people who are going to grow into their childbearing years in the years to come than any other religious group,” he said.

In fact, Islam is the only major religion expected to grow faster than the global population.

But the Pew report is mainly a story about Africa, a continent that is expected to double its population by 2050. That means 1 billion new people, divided primarily between Islam and Christianity.

In the United States, Muslims will edge upward from around 1 percent of the population to a little more than 2 percent. In Europe, the increase will be from around 6 percent to 10 percent.

Christianity is also growing because of high birth rates in Africa, which will be home to 40 percent of the faith by midcentury.

Hinduism and Judaism as well as folk and aboriginal religions in different parts of the world are also expected to grow.

Only Buddhism among the major faiths will stay constant, at about half a billion adherents.

British population studies professor David Voas said the results should be looked at country by country and with an understanding that greater numbers do not guarantee dominance.

“What really matters is economic and cultural productivity,” he said. “Does the country manage to translate its numbers into influence — both in the global economy and in terms of soft power?”

The researchers concede that measuring religious identification is an inexact science, and that they had to rely on official statistics in countries such as Egypt and China that allegedly underreport minority faiths. They also say demographic trends can shift in unforeseen ways because of natural catastrophes or human events. But they insist the data provide much valuable information about how religions are developing now.

Rabbi David Saperstein, the U.S. ambassador for religious freedom, who was also part of the panel, said the findings underscore the importance of interfaith understanding.

“If we have countries, as was discussed here, in sub-Saharan Africa, that are fairly evenly divided between Christians and Muslims,” he said, “then the ability of that country to hold together its unity, its common national identity, depends on the cooperative endeavors of the Muslim and the Christian communities.”