GENEVA —

In marking World Malaria Day on April 25, the World Health Organization says investing in malaria control is good health policy and makes good economic sense.

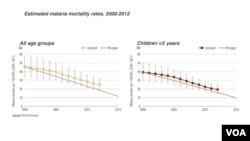

Great progress is being made in controlling malarial infection, and WHO officials think now is the time to capitalize on recent successes in the battle against this preventable and treatable disease. Dr. John Reeder, the WHO’s acting director of Global Malaria Program, says international funding for malaria control has increased from $100 million in 2000 to $1.94 billion in 2012, and that during that time malaria-related death rates have decreased 42 percent globally and 49 percent in Africa.

More than three million children’s lives have been saved, he says.

“So, clearly, ramping up investment in malaria can work and does work," he said. "And we have seen things like the vast expansion of bed net programs. Over the last couple of years, it has gone from 70 million nets that went out in 2012 to 136 million last year. This year there is going to be something in the region of 200 million nets put out there." Despite this progress, however, malaria remains a worldwide scourge, especially in Africa, where WHO figures show 207 million cases, including 627,000 deaths. The U.N. health agency says 90 percent of these deaths have occurred among children under five in sub-Saharan Africa.

WHO notes 80 percent of malaria cases are found in 18 African countries, with Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo accounting for half of those cases. It says malaria disproportionately affects the poor and thwarts African economies.

It estimates Africa loses $12 billion each year in lost productivity, and says the disease places a heavy burden on national health systems, accounting for as much as 40 percent of public health expenditure in some countries.

Reeder says it is possible to slow the spread of the disease. But, he notes, one of the problems affecting malaria control is the difficulty of delivering effective programs in the context of a weakened health system.

“So, malaria in itself is a disease, which has got particular needs and really needs an investment," he said. "But part of that investment really has got to be in strengthening health systems in a more general way."

Reeder says growing resistance to Artemisnin-based Combination Therapies, the most effective anti-malarials on the market, could unravel the hard-won gains to date.

Efforts to contain resistance and research and development of new tools to control the disease are important, he says, even if it requires lots of money.

The International Roll Back Malaria Program will need $5.1 billion every year through 2020 to provide insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, quick diagnostic testing and treatment for all those at risk.

Great progress is being made in controlling malarial infection, and WHO officials think now is the time to capitalize on recent successes in the battle against this preventable and treatable disease. Dr. John Reeder, the WHO’s acting director of Global Malaria Program, says international funding for malaria control has increased from $100 million in 2000 to $1.94 billion in 2012, and that during that time malaria-related death rates have decreased 42 percent globally and 49 percent in Africa.

More than three million children’s lives have been saved, he says.

“So, clearly, ramping up investment in malaria can work and does work," he said. "And we have seen things like the vast expansion of bed net programs. Over the last couple of years, it has gone from 70 million nets that went out in 2012 to 136 million last year. This year there is going to be something in the region of 200 million nets put out there." Despite this progress, however, malaria remains a worldwide scourge, especially in Africa, where WHO figures show 207 million cases, including 627,000 deaths. The U.N. health agency says 90 percent of these deaths have occurred among children under five in sub-Saharan Africa.

WHO notes 80 percent of malaria cases are found in 18 African countries, with Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo accounting for half of those cases. It says malaria disproportionately affects the poor and thwarts African economies.

It estimates Africa loses $12 billion each year in lost productivity, and says the disease places a heavy burden on national health systems, accounting for as much as 40 percent of public health expenditure in some countries.

Reeder says it is possible to slow the spread of the disease. But, he notes, one of the problems affecting malaria control is the difficulty of delivering effective programs in the context of a weakened health system.

“So, malaria in itself is a disease, which has got particular needs and really needs an investment," he said. "But part of that investment really has got to be in strengthening health systems in a more general way."

Reeder says growing resistance to Artemisnin-based Combination Therapies, the most effective anti-malarials on the market, could unravel the hard-won gains to date.

Efforts to contain resistance and research and development of new tools to control the disease are important, he says, even if it requires lots of money.

The International Roll Back Malaria Program will need $5.1 billion every year through 2020 to provide insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, quick diagnostic testing and treatment for all those at risk.