This is Part Three of a five-part series on creative African artists

Continue to Parts: 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5

His hands are big and hard and stained with red, blue, yellow and green paint.

They make light work of the tough wire which he twists and bends into the shape of a wheel, his thick fingers blurring together because of the speed at which he works. He grabs a hammer and bangs a chisel. Chips of wood fly through the air.

Admire Munyuki’s in a wheelchair, but he’s never still, never at rest. “I’ll sleep when I’m dead!” he says. “Some people like to say I am ‘confined’ to this chair. But they don’t know that I am so free, I actually have wings! Can you see them? Look!” he shouts, casting his anvil aside and flapping his arms manically.

The eccentric Zimbabwean with the smile that never fades is surrounded by children. “They keep me young!” he laughs. “They make me strong; bless them.”

Munyuki sells his wares at public events throughout southern Africa. “Wherever I think children will be, I go. I go everywhere except Zimbabwe,” he told VOA at a food festival in Cape Town. “That is very sad, because it is my home country. But unfortunately economic opportunities are very limited there, even though I think the situation there is improving.”

Youngsters watch, wide eyed, as he carves yet another miniature tractor from a block of wood. With wire, he fashions rear and front axles and a steering wheel and column. He cuts wheels from a bald tire and screws them into his creation.

Munyuki passes his finished work to a boy, who beams in appreciation and rushes to test it on a nearby gravel path, a gaggle of screaming friends snapping at his heels.

Grinning, he said, “I make the kids’ dreams; I like it when they’re happy.”

‘I do things for myself’

Munyuki described himself as a “recycler artist. I am proud because I have actually never bought anything that I use to make my toy tractors – except sometimes I buy the paint from a man I know, but even that paint is extra paint from jobs he does….”

He said he spends his life at places most people avoid – on dumps and scrapheaps. “That is where I get my riches,” Munyuki commented. “Wherever I am, the first place I visit is a (city or town) scrapheap.”

Given recent events in the man’s life, one would be forgiven for suggesting that the scrapheap is exactly where his life has been consigned. Evicted from the tobacco farm he worked on and loved 10 years ago, and shortly thereafter diagnosed with a spinal condition that paralyzed him from the waist down, Munyuki’s position seemed a hopeless one. But he was at pains to insist that he never saw it that way.

“I just said to myself, ‘When something hard comes into your life, you just have to accept it and move on.’ If I did not have this attitude I would have ended my life a long time ago. I have learned to survive with what I have,” he said.

Munyuki acknowledged it’s difficult for him to do the physical work he does. “It is very tough; it’s quite challenging. But a man has got to do what he’s got to do to survive, otherwise no one will give you bread on the table. You’ve got to do it (for yourself).”

He’s been independent ever since he can remember. “I am proud to say that I have never begged for a coin in my life. When I see all these other lame and blind beggars from Zimbabwe on the streets, I feel sorry for them. I could not survive like that, by accepting handouts from others. I would not be able to live with myself,” he said.

War veterans light his fire

To Admire Munyuki, the tractors he makes are much more than mere toys for children. They represent his hold onto a past he said is “always” with him.

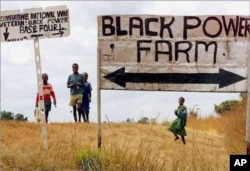

“I grew up on a tobacco farm in Marondera district (in eastern Zimbabwe). But (President Robert) Mugabe’s war veterans attacked and took that farm in 2002. They didn’t only kick the farmer off the land but also all his workers, also me,” he explained.

He added, “As a child, I was always attracted to those big vehicles on the farm. I loved tractors especially. Nothing would make me happier than when my father or one of the other workers would give me a lift on a tractor. Later, I even learned to repair those tractors. Now I make them as toys, as I remember them from when I was young….”

The land seizures which began in 2000 precipitated Zimbabwe’s decline. They also helped to destroy a once-thriving agriculture sector…and to extinguish Munyuki’s life as he knew it.

But where others would perhaps have seen only adversity, the Zimbabwean crafter said he saw opportunity. “I was sad to stop my work on the farm. I loved that land,” he said. “But I knew I had the skills to carry on in life. Those so-called war veterans, they tried to take my light away. But they only made another kind of fire inside me.”

Together in peace

It’s the beat of Africa that helps to fan the flames burning inside Munyuki. He also makes djembe drums. He lines his instruments – made from the hardest wood he’s able to find – with ropes.

“It is the ropes that actually tune the drums,” he explained. Djembes originated in West Africa and are played with bare hands. According to the Bamana people of Mali, “djembe” comes from the saying “Anke djé, anke bé,” or “Everyone gather together in peace.”

Munyuki makes his drumheads from goatskin and pigskin. “Djembes are one of the best drums because they can do so many things and can be used in so much different music,” Munyuki said.

Traditionally in Africa, djembes are played by men. But Munyuki encourages women to play it. “Why not,” he asked. “These are new times and women should be able to do everything that men do. In fact, I have seen women who are much better djembe players than men. Men try to beat the djembe as hard as possible, but drum playing is not about loudness; it is about sensitivity to beat and it is about creating the proper rhythms.”

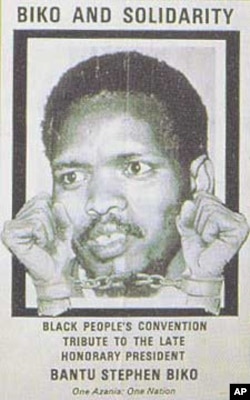

But ironically it wasn’t an African experience that began Munyuki’s quest to create “perfect” djembes. Being Zimbabwean, he’d grown up listening to the mbira thumb piano – not djembe drums. But, as a teenager in the early 1980s, he said he heard a recording of British singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel’s “Biko,” a song about the killing in custody of South African black consciousness activist Steve Biko by apartheid police in 1977.

“The powerful way in which Peter Gabriel used a djembe to drive that song really moved me a lot, and it drew me towards the drum,” Munyuki explained.

With Paul Simon’s landmark recording Graceland in 1986, for which the American artist extensively employed the djembe drum, Munyuki said the worldwide embrace of it as an international, and not just an African, musical instrument was complete.

That’s continued until today, with modern pop and rock music bands employing the djembe, including Irish super-group U2.

‘They fall in love…’

Wherever he goes, Munyuki’s warmth and friendliness ensure he’s a popular presence. There are always people around him, always children begging their parents for a tractor, or pleading with him for a chance to beat his drums with their tiny hands.

But he emphasized, “When the people are near me, it’s got nothing to do with me; it’s because of my products. People they come with kids, then they tend to fall in love with my things, then they love me also – so we make friendship together.”

Munyuki doesn’t know how many tractors and drums he’s sold across southern Africa since 2002.

Keeping those kinds of figures, he said, isn’t in his nature. Then he added, “Maybe I’ve sold a thousand…a thousand pieces of me, a thousand pieces of joy.”