Zambia’s government has denied that the country faces an economic crisis, despite widespread concerns that the money it owes China is reaching unsustainable levels.

Speaking from Lusaka, Amos Chanda, spokesperson for President Edgar Lungu, told VOA’s Daybreak Africa that, while Zambia may have economic challenges, it’s far from a debt crisis.

“The economy is going at four percent. But that is not to say there is no economic problem. There are economic problems, but you can’t call them a crisis,” Chanda said.

He also denied reports that Chinese companies were taking over public assets.

“There is no single Chinese company taking over,” he said.

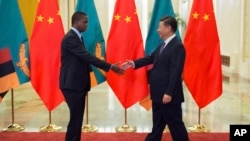

Zambia secured a $30 million interest-free loan and $30 million grant at the recent Forum for China-Africa Cooperation, held last week in Beijing, Chanda added.

Chinese takeover?

Concerns remain high that China is pursuing debt-trap diplomacy with the aim of taking over Africa’s strategic assets. One such example comes from Africa Confidential, which, earlier this month, concluded that “the state-owned TV and radio news channel ZNBC is already Chinese-owned.”

Based on investigative reports from local media, however, the reality appears more complicated.

In 2017, the Zambian government created a joint venture, TopStar Communications Limited, to digitize its broadcast infrastructure, Tumfweko, a local news site, reported last year.

The Chinese firm Start Times owns 60 percent of TopStar, and ZNBC, a Zambian state broadcaster, owns 40 percent. The company is overseeing the distribution of some 1.25 million set-top boxes throughout the country, while generating revenue to repay a $273 million Chinese loan for the project.

Nick Branson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, told VOA rumors and ongoing conversations can’t easily be separated from facts in countries like Zambia, where few decisions happen transparently. And although the government would be very reluctant to sell assets, it isn’t in complete control of its public finances, and it’s struggling to manage debts that were acquired in the last three years.

“The sale of a strategic national utility, obviously, while not desirable, is a plausible response - whether it’s an advised one or not, really, is a different matter,” Branson said.

Dynasty ties

China’s longstanding ties to political dynasties in Africa, while touted as a sign of Beijing’s loyalty to the continent, often do more harm than good. That’s because African leaders, emboldened by these connections, pursue so-called “vanity projects” that benefit only the elite. These countries tend to face few protests from opposition, civil society, or China itself, Branson said.

Governments with well-defined national planning documents, meanwhile, have had better success converting Chinese pledges into realized deals and then servicing their loans. Insight into their countries’ infrastructure needs has allowed these governments to enter negotiations with more bargaining power and approach multiple donors to help finance their development, Branson said. And that often leads to better deals for debtor countries.

“When there are multiple partners at play, it’s a lot easier to come up with a concrete proposal and play different potential funders off against each other and try to gain more concessions,” Branson said.

A lack of transparency also leads to problems, Branson said. Neither China nor African countries want the specifics of their deals subjected to public scrutiny, and those political factors will prevent clarity of the exact extent to which pledges are being fulfilled, Branson said.

“I think it suits all actors from all sides to keep matters as opaque as possible,” he added.

‘Negotiating capital’

Resource-rich countries like Angola, a longtime China partner, have benefited from being able to export raw materials that China wants, making it straightforward to service loans. In Angola’s case, that’s translated into oil for infrastructure.

But for smaller countries, repayment strategies become tricky. East African nations, for example, may struggle to repay multi-billion-dollar loans for railway projects that will take many years to pay for themselves.

As for the possibility that China might seize African assets, Branson said it’s a risk, albeit not an imminent one. Still, nations unable to export commodities will likely struggle to service their debt in the long term.

“The level of negotiating capital that a lot of these African nations have is relatively constrained,” Branson said.

James Butty contributed to this story.