Reporter Malivika Austere and VOA's Central African service contributed to this report.

“I was with my children when they died,” said Lydia Uwamwezi, recalling the 100 days of genocide that began 25 years ago this Sunday in Rwanda.

“There is a lake between Kigina and Nyarubuye. That is where the mob took us. They were tired of using machetes, so they threw my children into the lake.”

WATCH: Rwanda Survivor Lydia Uwamwezi

Uwamwezi, now 46, was spared. In despair, she threw her baby carrier into the lake after her drowned children. The Hutu attackers retrieved it and later raped her repeatedly, telling her she must bear them Hutu children to replace the Tutsi ones they had just murdered.

Uwamwezi also lost her husband and home during those days. She never remarried or had other children. After government-provided reconciliation training, she has forgiven her attackers.

“If you have a grudge at heart, you can never live well with your neighbors,” she said.

And they do. Today, Tutsis and Hutus, once on opposite sides of the mass killings, live in the same neighborhoods in a country where health care is provided, streets are clean and the government urges people to forget ethnic distinctions and consider themselves Rwandans.

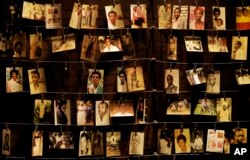

On April 7, Rwandans commemorate the genocide that left hundreds of thousands of people dead, with ceremonies themed "Never Again." Genocide prevention will also be highlighted. The United Nations holds an annual memoriam. Since Rwanda, mass killings have occurred in Bosnia, Sudan, and Myanmar.

100-day massacre

Rwanda’s violence pitted the minority Tutsis, traditionally the wealthy class, against the majority Hutus, who tended to be middle and lower class. For generations, the distinction was more economic than ethnic.

In 1935, Belgian colonists cemented the distinction by mandating separate identity cards for Tutsis and Hutus. Differences in economics and social status sparked angry resentment and division.

Three years of civil war preceded the genocide. The Rwandan Patriotic Front rebel movement was led by Tutsis who for years had been living as refugees in neighboring Uganda. Their push to reclaim territory in their native country was seen by some as the aggravating factor leading to mass slaughter. The war also brought a large number of weapons into the country.

WATCH: Rwanda Survivor Immaculée Mukantabana

When a plane carrying the Rwandan and Burundian presidents was shot down April 6, 1994, by unidentified attackers, the situation exploded. Within hours, extremist Hutus used radio and word of mouth to incite attacks against Tutsis, Hutus married to Tutsis, and the Twa — descendants of indigenous Rwandans. Weapons meant to defend the country were used instead to murder fellow Rwandans.

The combatants were not always clearly defined. Not all Tutsis were aligned with the RPF, and not all Hutus participated in the killings. What is clear is the death toll. At the end of 100 days, about 800,000 Rwandans — including 70% of the country’s Tutsi population — were dead. Some estimates put the total at a million.

Haunted by pleas

Delphine Vumera remembers her nephew's voice. Other survivors talk about the gunshots and screams, but she is haunted by his pleas.

“The same picture keeps coming back to me,” she said, “because each time they sent out mobs of killers, we lost people. The noise keeps scaring me, even today.”

Vumera remembers her nephew asking her not to leave him.

“My mother had just been killed along with the others,” she said. “The child expected me to save him, but it was impossible. I was trying to save my own life. He was still calling me when they killed him,” she said.

After the massacre, the RPF gained control of the capital, Kigali. A couple of weeks later, they controlled the entire country. The mass slaughter had ended, but not the pain and hardship of the survivors.

Recovery and forgiveness

The killings ended, but the trauma endured.

“We feared to go back to the places we had lived before," Vumera said. "People would never come close to each other.”

Food and housing were scarce, but Vumera eventually healed. She went back to school and also married.

“We attended several meetings where they helped us to recover from trauma,” she said. “Now, we are like other people.”

Rwanda’s current population is young, though thousands of the country's 24-year-olds were the result of rape during the genocide. Many say they have benefited from facing their origins head-on.

In March, a young man named Robert told The New York Times, “The fact that my mother disclosed to me that I was born from genocide rape made me increase my love for her.”

Another young man named Claude said, “I will not be defined by the way I was born, as a young person born from rape. I want to build a good future and be a responsible person in my life.”

WATCH: Rwanda Survivor Dieudonne Nzeyimana

Others, like Dieudonne Nzeyimana, 37, were orphaned by the killings. He told VOA he is still “furious” about the loss of his family, but said he strives to forgive, because “forgiveness relieves the person who forgives (more) than it does to the one forgiven.”

Nzeyimana said he forgives, “even though some of the killers didn’t ask for forgiveness, and others never acknowledged what they did.”

Vumera had a transformative experience after the killings.

“Families kept coming to us to ask for forgiveness,” she said. “I had already forgiven them in my heart. Today, I have no grudge with anyone.”

Paul Kagame, commander of the rebel RPF, has since turned his army into the ruling political party. He has been president since 2000. Many credit his leadership for Rwanda’s transformation, which included establishing a United Nations war crimes court that sentenced 38 of the ringleaders to long prison terms.

Traditional Rwandan community courts, known as gacaca, were assigned to deal with 2 million lesser participants. But critics say the trials have been focused on Hutus when some Tutsis should also be held accountable.

WATCH: Rwanda Survivor Innocent Kabirizi

International aid has helped Rwanda rebuild its infrastructure. It’s no wonder, then, that the government paints a rosy picture of its recovery. Rwandan officials say their citizens have universal health care; maternal health is among the best in Africa; infant mortality is low; all children get 12 years of education; and universities accept students on the basis of merit rather than quota.

Officials say more than 70% of the nation has access to clean drinking water. More than a million people have been taken out of poverty, though the poverty rate is still 45%.

Kagame keeps a tight rein on Rwanda’s news media. He has told reporters he hates the “cynicism” of U.S. publications such as The New York Times and The Washington Post.

Kagame has also been accused of holding too tightly to power. The U.S. State Department has reports of arbitrary detention, and disappearances of political enemies and journalists. State security forces have been accused of torture.

Rwandans recently voted to amend the constitution to give Kagame a third seven-year term. Though he had competition from two other candidates, election officials say he won 99% of the vote. But international observers have reported irregularities in the tabulation process.

Kagame’s critics point to these issues and others, while his supporters say Rwanda needed strong authority to develop the way it has.

WATCH: Rwanda Survivor Innocent Gasingwa

The government’s heavy emphasis on reconciliation may have influenced the outlook of genocide survivors. Nzeyimana has internalized Kagame’s emphasis on unity. He says being Rwandan is more important than being Hutu or Tutsi.

“A reconciled nation is a country where its citizens live in harmony without any form of segregation," he said, "be it based on race, tribe, height or origin. A country that offers equal opportunity to all citizens.”

WATCH: 25 years after Rwanda