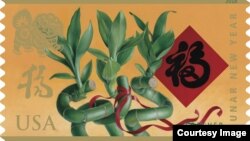

You may not be familiar with the name Kam Mak, but you've probably seen his work. In 2008, the Chinese-American artist was selected by the U.S. Postal Service to create an annual stamp through 2019 for its Celebrating Lunar New Year series.

The Year of the Dog stamp is his latest, and Mak says it highlights some of the holiday's traditions.

"In the Year of the Dog stamp I decided to use three stalks of lucky bamboo. In Chinese tradition, three lucky bamboo symbolize first, blessing and luck, second is long life, and third is wealth. I also included the pasting of the Fu character, and that means blessing and luck."

The Lunar New Year stamps date back to the 1980's, when the Organization of Chinese Americans, now known as OCA – Asian Pacific American Advocates, began urging the postal service to issue a stamp honoring the contributions of Chinese Americans in the U.S.

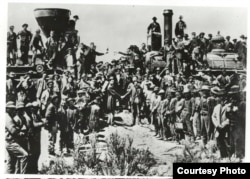

Mak explains that Jean Chen, one of their members, led the way after she came across a book about the history of the Transcontinental Railroad with a photo showing only Caucasian workers celebrating the completion of the railroad in 1869.

"She was incensed to not see one Chinese American in any of those photos. And she felt that is not right. And she came up with the idea of lobbying the U.S. Postal Service to have some kind of stamp to pay honor to these Chinese Americans who helped build the railroad. That railroad transformed America and a lot of Chinese people gave their lives building that."

The first Lunar New Year stamp, issued in 1992, was designed by Hawaii graphic artist, Clarence Lee. Due to its popularity, the U.S. Postal Service commissioned Lee to design a series depicting all 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac. Mak's series, which celebrates some of the holiday customs and traditions that have endured throughout time, incorporates Lee's paper-cut designs.

His favorite, he says, features narcissus flowers, issued in 2010 for the Year of the Tiger. "It comes with lots of memory, because it was something that my grandmother would cultivate right before the lunar new year and as a little boy I always watched her doing it ...And the fragrance from the flower always reminds me lunar new year is coming and always brings back, really fond memory being with my grandma.

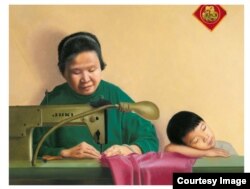

Mak, who was born in Hong Kong, immigrated to America with his family in 1971, and grew up in New York City’s Chinatown. There, the 10-year-old faced language barriers and the challenge of adjusting to a new life.

"My Dad was a dishwasher in a Chinese restaurant and he worked six days a week," he said. "And my Mom was working in a sweatshop, six days a week, 12 hours a day. They struggled, because the pay’s really low ... they struggled just to take care of us."

Mak recalls during that time, gangs were rampant in Chinatown and trying to recruit new members. His friend joined a gang. "One day I heard that my friend got shot in a Chinese Theater," Mak said. "And the whole scenario, really scared me straight. And I realized, 'Oh boy, I want to make sure that I don’t end up being in that situation.' And think from then on, I really started taking school very seriously. Because I think that was really my way out."

Mak was not a good student, but he was good at making pictures. Before long, he got involved with the City Art Workshop, which allowed inner-city youth, like him, to explore the arts. Today, in his 50s, Mak is a professor at New York's Fashion Institute of Technology, where he teaches painting. He’s also illustrated numerous books, including a retelling of an old Chinese folktale, The Dragon Prince, by renowned author Laurence Yep.

Eventually, Mak illustrated and wrote his own picture book called My Chinatown: One Year In Poems. It’s about a little boy growing up in Chinatown. Through an organization called Behind the Book, he shares his immigrant experience with New York City students.

"[They] are mostly Latinos and African American kids (from the) inner city. So besides reading them the book, I take them out to Chinatown and have them experience all the things that I experienced growing up ... I just want to stir their imaginations and want them to learn about other cultures, besides what they only know in their own neighborhood."

And he wants the people he meets to be proud of who they are, and not feel ashamed if they're different. He recalled a talk at a public school in Chinatown.

"And so after my presentation to these group of kids, a bunch of Chinese kids came to me very emotionally (and said), 'Kam, I’m so happy there’s a book that is about me.' I say, 'Yes, this book is about all our experiences, our similar experiences.' So at that moment, I felt really emotional because, wow, the book itself had moved other kids, and they would not feel that they are isolated, that there’s actually a book that actually plays a very positive light about how they grew up and it’s something they can relate to. And so I think that’s a very positive thing."

For Kam Mak, carrying on the legacy of the Lunar New Year stamps, and Chinese culture and heritage, is not only a huge responsibility, but a personal mission, as well.