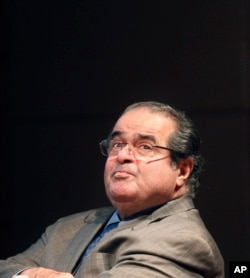

When Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was found dead at a remote Texas resort, a high-stakes political moment arose for former President Barack Obama.

The timing, one year ago this week, was tricky: Obama was less than one year away from the end of his time in office, and the race for the next president was well underway.

Scalia’s death was sudden, and his vacancy on the Supreme Court had the potential to tip the balance of the court, putting liberal-minded justices in charge for the first time since former President Richard Nixon was in office.

Much depended on which president chose the next justice: Obama, or his successor after the presidential election in November. The battle over that question still shapes U.S. politics today.

Scalia, a provocative, controversial, charismatic and highly respected justice, was a staunch conservative and a forceful originalist — that is, a justice whose interpretation of the U.S. Constitution is based on discerning what the Founding Fathers intended in 1787.

In other words, to Scalia the Constitution was not a guideline that evolved throughout history, nor should it be approached as anything other than what it was.

"I will stipulate that [originalism] is not perfect," Scalia said during a 2010 lecture at the University of Virginia. But "in ease of lawyerly application, never mind legitimacy and predictability, it far surpasses the competition."

Moving quickly, Obama nominated Judge Merrick Garland just a month later to fill the court vacancy.

Garland, the chief judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, is widely viewed as a centrist judge who, if confirmed, would be a voice of moderation on the court.

In the days following Scalia's death, most political analysts predicted a nomination by Obama would be contentious — and it was.

Republicans responded to Obama’s pick by refusing to vet him. Invoking the so-called “Thurmond rule,” senators argued that the vacancy should be filled by the next president.

The Thurmond rule is not a law. Rather, it is an unwritten rule that says a judicial nominee should not be confirmed in the months leading up to an election. It dates to 1968, when Senator Strom Thurmond, a Republican of South Carolina, blocked President Lyndon B. Johnson’s appointment of Justice Abe Fortas as chief justice.

The administration, in turn, argued that Obama was bound to fill the seat under the U.S. Constitution.

“I’m going to fulfill my constitutional responsibilities to nominate a successor in due time,” said Obama shortly after Scalia’s death was confirmed. “There will be plenty of time for me to do so, and for the Senate to fulfill its responsibility to give that person a fair hearing and a timely vote."

But congressional Republicans retorted that Obama should let the “people decide,” a reference to the November presidential election.

And they pledged to block any consideration of Garland. They fulfilled that promise, blocking the nomination from going forward all the way up to and past the election of Donald Trump.

On January 3, the Merrick nomination expired.

The GOP strategy paid off politically, giving Trump the court vacancy to fill, and setting a new precedent: It was the first time an election-season Supreme Court pick by an outgoing president had been successfully blocked.

Judge Neil Gorsuch, a conservative and constitutional originalist in the mold of Scalia, was Trump’s choice.

“When Justice Scalia passed away suddenly last February, I made a promise to the American people: If I were elected president, I would find the very best judge in the country for the Supreme Court," said Trump during a public event at the White House, announcing his candidate. "Judge Gorsuch has outstanding legal skills, a brilliant mind, tremendous discipline and has earned bipartisan support.”

If he is confirmed, Gorsuch would bring back the 5-4 split between conservatives and liberals on the court.

And the court’s swing vote would return to Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, whose rulings have been on both the left and right of the political spectrum.