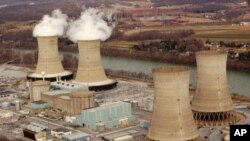

Nuclear power plants are clean, efficient and silent. But they face complex safety issues. There is the danger of radiation leaks. They are vulnerable to terrorist attacks. And perhaps most vexing of all, they produce large amounts of waste in the form of spent uranium fuel, which remains dangerously radioactive for thousands or perhaps millions of years. How and where to safely store that waste has been a central question in the decades-old debate over nuclear energy.

The catastrophic failure of Japan's Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant, following the March 11 earthquake and tsunami, spotlighted the terrible risks of generating electricity with nuclear reactors. It also focused renewed attention on the dangers of keeping the reactors' highly radioactive spent fuel in temporary storage, on-site. Over the past six decades, the world has built some 400 nuclear plants, and none of them has a permanent, long-term storage plan for this lethal waste.

Linda Gunter is an international specialist at Beyond Nuclear, a Washington-based environmental group . "The nuclear waste problem has never been solved and there is a strong possibility that it will never be solved and therefore we talked about it as the Achilles hill of the nuclear industry," she said.

Around the world, nuclear waste sits at the reactor sites, either in deep water-filled concrete pools or in steel-reinforced cement casks, located just outside the reactor buildings. "In the case of the Fukushima design, which is the GE Mark One reactor -- of which there are 23 in the U.S. -- that fuel in the pool is sitting on the roof of the building outside containment, vulnerable to attack or to breach. If there is any kind of an accident that opens up that pool, that inventory gets released to the environment. That is a lot of radioactivity," she said.

Nuclear industry experts say the dangers of on-site nuke waste storage have been greatly exaggerated by critics. The Nuclear Energy Institute, N.E.I., is a major political voice for the industry in the United States. Adrian Heymer is executive director of NEI's strategic programs.

"The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has estimated it is safe for another 100 years at the site in the locations where it is, whether it is in the fuel pools or whether it is in dry-cask storage," he said.

This is a dry-cask or reinforced-concrete container of nuclear waste at the San Onofre Nuclear Plant, located in southern California. Inside that thick cement casing is a large quantity of radioactive waste, walking distance from the reactors. It's just a fraction of the 70,000 metric tons of nuclear waste that U.S. nuclear plants have produced over the past sixty years, according to the U.S. Government Accounting Office.

NEI's Adrian Heymer says because of recent events at the damaged Fukushima plant, where exposed uranium waste has leaked large amounts of radiation, there is renewed interest in the United states in moving waste from the 104 operating reactors, at 67 sites around the country, out of water-filled pools into dry-cast storage and then to a interim, off-site storage location.

“I think that with the events in Japan, is important that we move forward with this interim storage activity as soon as possible, so we can start moving fuel away into a safer location, as opposed to having them spread around in 67 locations,” he said.

In 2002, the U.S. seemed on the verge of a permanent nuclear waste storage solution. The U.S. Congress gave the go-ahead to the Yucca Mountain project, to develop a deep, subterranean nuclear waste burial site about 160 kilometers from Las Vegas, Nevada. The project has been controversial from the start. Critics say transporting nuclear waste to Yucca Mountain would be too risky. In early 2009, after several billion dollars had already been spent constructing the underground facility, President Obama called a halt to the project.

The future of the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste site remains unclear.

Adrian Heymer at NEI believes Yucca Mountain is still a viable option and attempts to close it, he says, are being driven by political, not technical issues.

But until such large permanent storage sites can be developed, the world's 400 nuclear reactors will continue storing their nuclear waste close to home. And according to Chris Flavin, president of the Worldwatch Institute, an environmental watch-dog group in Washington, the waste storage issue is a big problem for nuclear power advocates.

“The fact that the Japanese were actually storing nuclear waste, which they had no other way of dealing with on the site -- and that that sort of contributed to the severity of the accident in the long term consequences -- I think that is going to be one of the big additional drags on nuclear power going forward," he said.

The average life of a nuclear power plant is forty years. According to the Nuclear Energy Institute, 61 plants in the U.S., more than half the total, are applying for re-licensing to extend their operations for another 20 years. The Institute is now studying the possibility of requesting an additional 20-year extension, which would bring the reactors' maximum life to 80 years. Approval of these licenses might well hinge on the public's hope that the nuclear waste storage problem will eventually be solved.

In an earlier version of this story we incorrectly reported the total number of years for the life U.S. nuclear reactors if applications for re-licensing are approved. The correct number is 80 years. VOA regrets the error.