When the dust of Egypt's revolution began to settle and the country struggled toward a democratic government, many of the women who stood side-by-side with men in Cairo's Tahrir Square were struck that not one woman was named to the committee to reform the constitution.

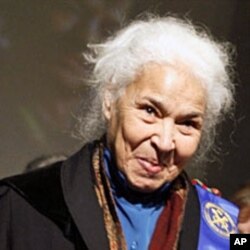

Prominent Egyptian author and activist Nawaal el-Saadawi says that angered women who marched on equal footing with men to oust former President Hosni Mubarak - only to find themselves thrown back to the old ways and excluded from the new order. She said the women felt their rights were being taken from them.

"Women’s rights cannot be given ... We have to take [them] by the political power of women," she said. "And that’s why we are reestablishing our Egyptian Women Union."

Al-Saadawi says women were scattered, weak and divided under the former regime and efforts are under way to unite them.

"So we are trying to bring women together to have political power so that we can fight for our rights in a collective group," al-Saadawi explained.

Fears of being excluded also echoed in neighboring Tunisia among many of the women who participated in the revolution to oust the Ben-Ali regime. Isobel Coleman, Senior Fellow for U.S. Foreign Policy and Director of the Women and Foreign Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations says Tunisian women worry about the return to power of some of the more conservative elements might try to repeal Tunisia's progressive family laws.

Coleman notes that Iraq saw a similar situation a few years ago, when the country's new government tried to rescind the family law that had been in place under the Baathist regime for a long time and replace it with religious law. Many Iraqi women favored the implementation of Islamic law, says Coleman, while others feared it would mean a regression of their rights.

But it remains unclear how women will benefit from revolutionary change in the Middle East. Coleman says the first consequence has been the "fall of more secular-oriented governments that have used their authoritarian power to push through, often against the wishes of powerful voices within the country, more progressive rights for women."

She says governments are now going to have grapple with the possible resurgence of Islamists. "And women's rights will be a very clear litmus test of whether they are finding compatibility between Islam and democracy or not," noted Coleman.

Crucial to finding that compatibility is a clear definition of women's roles in society. The problem, says Shadi Hamid, a Fellow at the Brookings Institution and Director of Research at the Brookings Doha Center, is that there is no clear consensus around the role women should play, particularly in Arab society. That is partially due to the perception that women's rights are more of a Western concept.

"And that's why we see the odd phenomenon in some countries of Arab women working against their own supposed 'rights,' " explained Hamid. "And we see this, for example, in some of the Gulf countries where women have actually advocated against being given the right to vote or have not been in favor of, supposedly, pro-Western reform."

Cheryl Benard, a Senior Analyst with the RAND Corporation, says there are women who have made a "generations-long bargain" with the existing society, where they accept that they are going to be in an inferior position, and they believe that, in exchange for that, they get something.

"They get security. They get the shelter of their relatives taking care of them," said Benard. "So those women, I think, are, in part, afraid of change because they are afraid of what it will mean if that traditional, conservative protection maybe falls away and they have to be in charge of themselves."

Benard says that fear is less prevalent among the young and educated urban populations, leaving a gap between rural and urbal populations. Equally pronounced are the gaps that stand out in education, political participation and labor in the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2010.

Click tabs and mouse over countries for more information:

The report also reveals some interesting extremes. Women in the United Arab Emirates, for example, surpass men in educational attainment by two points, but lag behind men in Yemen by about 36 percentage points.

But the Rand Corporation's Benard cautions that the statistics don't tell the whole story. She says the overall, long-term picture is promising. For example, countries like Jordan and Saudi Arabia no longer publish grades at universities because the women are so far ahead of the men that they don’t want to embarrass the men.

"Yes there are countries where women lag behind, where they are more of the illiterates compared to men. But if you look at it generationally, first of all it tends to be often not really true anymore of the younger women," Benard said. "And if you look at it regionally - urban vs. rural areas - it’s also not quite true. There have been a lot of changes going on and women have actually even pulled ahead of men in the educational field in some areas. The same is true economically."

But progress in education has not been matched on the political front. Women parliamentarians remain absent in places like Saudi Arabia and Qatar and their share of cabinet positions in most other countries is contingent on a quota-based system.

"There are a couple different models here," says Hamid of Brookings. "One model ... that you’ve seen in Morocco and Jordan, is where the regime, or in this case the monarchies, ignore popular opinions and effectively impose changes in the sphere of women’s participation."

Hamid says the majority opinion is not very supportive of a very visible role for women. "And that's why when there aren't quotas in the political system, women have immense difficulties winning even the smallest number of seats in parliamentary elections."

Top-down efforts, says Hamid, don’t have the support of the larger population. Many people don't feel comfortable voting women into senior positions, and not all women are in favor of women's empowerment. He says a lot of women's empowerment efforts come from the secular, elite side of society, which is a minority in Arab society.

"The population will go along with it, but it’s not really based on a cultural shift," he said. "It’s not based on a shift in attitudes. And without that shift in attitudes at the grassroots level, change is not going to be deep or sustainable ... The question is how do you initiate a grassroots process in favor of women’s empowerment?"

As democracy begins to emerge in the Middle East, Hamid says women and liberal groups advocating their rights will have greater political space and room to make their voices heard.

"We have to question the whole premise that equal rights in the Western sense, is something that all societies would like and want to fight for," he cautioned. "And it appears to be the case that Arab societies aren’t willing to go all the way to where the West is ... I think everyone supports women’s empowerment. But I think it means different things to different people."

While Benard of the RAND Corporation agrees that the region has to find its own formula for women's empowerment, she says the women and their families who participated in the revolutions embody a change in Middle Eastern women that has disspelled some of the Western misconceptions.

"This is quite a different picture of the role of women in the Middle East ... where one thought that the families were all ultra-conservative, [that] they don’t want the women to be out and about, [that] they don’t think that the public space is something appropriate for women," Benard said. "That is not what we have seen. We’ve also seen women ... online, taking a leadership role often and organizing this and calling for things to happen."

So how will Middle Eastern women shape their own future in the new order?

The populations of the region are able to determine their own destiny, says Benard, and are more capable than they are given credit for. "Sometimes, she says, "the best thing you can do for somebody is [to] get out of their way."