When seven states, led by Texas, filed suit against the federal government last week to force it to kill the DACA program, they were heading down a path they already had taken to eliminate another controversial immigration policy.

DACA – the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals – allows young people who came to the United States as undocumented children to live and work legally in the country.

The Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents Program, or DAPA, was proposed at the same time as an executive action that would have protected about 4 million residents from deportation, most of them parents of American citizens.

But DAPA never went into effect because the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in 2014.

The suit against DAPA initially was filed in a Texas District Court by 26 states, led by Texas.

“The courts blocked DAPA after I led another state coalition challenging its constitutionality all the way to the Supreme Court,” Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton said at a press conference announcing the suit last week. “Our coalition is confident that ultimately, through our federal lawsuit, DACA will meet the same fate.”

The DACA suit is on the same track, initially filed with the same judge in Brownsville, Texas, after which it is likely to be appealed to the Fifth District Court of Appeals and then to the Supreme Court.

But there are differences.

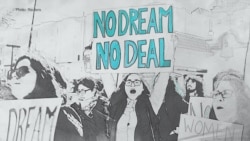

While DAPA never took effect, more than 700,000 young people participate in DACA. And the policy is overwhelmingly popular with the American public.

President Donald Trump ended DACA last September, saying that Congress should pass legislation to make the policy legal. Congress has been unable, though, to find agreement on DACA.

Since then, courts in three jurisdictions have ruled that the program must continue while its constitutionality is tested. So U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS, is still taking applications for two-year DACA renewals.

USCIS may be forced to take new applications for DACA on July 23 if the federal government is unable to adequately explain why it ended the policy. The Texas lawsuit has asked for a hearing prior to that date.

DACA has three favorable rulings. With a fourth likely to be unfavorable, the federal government could find itself caught between conflicting court orders.

Immigration lawyer Leon Fresco says the situation is "not very common." But he adds, "So long as even one nationwide injunction is in place, DACA continues to operate. Only the Supreme Court can wipe the slate clean here."

The high court will have to decide whether DACA should go the way of DAPA, or not.