Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed support for the enactment of the Paris climate agreement this year in a meeting Tuesday at the White House. Support for the agreement falls short of a commitment to ratify that U.S. President Barack Obama had been hoping for.

"We discussed how we can as quickly as possible bring the Paris agreement into place, [and] how we can make sure that climate financing that's necessary for India to be able to embark on its bold vision for solar energy and clean energy ... can be accomplished," Obama said afterward.

If India had ratified the deal, it would have gone into force well ahead of the original 2020 target and sent a strong signal that developing countries are serious about fighting climate change — arguments the president likely impressed on his Indian counterpart in talks. But the response fell short of expectations.

"I believe what Prime Minister Modi has said about this is that India shares the objective that the United States has laid out, which is to see the agreement come into force this year," White House spokesman Josh Earnest said at a news briefing after Obama met with Modi.

Obama and Modi "really have a meeting of the minds" on climate change and clean energy, says World Resources Institute senior fellow Andrew Light, a former State Department adviser on India and climate issues. Both leaders consider it a moral issue and an obligation to future generations, Light says, and both want progress to be part of their legacies.

That has translated into constructive cooperation, he notes. Over the past two years, Light says the two have expanded or created 15 joint climate and energy programs.

Modi, speaking alongside Obama after their meeting, noted that Washington and New Delhi have been cooperating on a range of issues of global concern, including nuclear security and terrorism, as well as climate change.

Emphasis on solar

But, regarding energy programs, critics note that India has committed to very little under the Paris agreement. They say much more will be needed from India and the rest of the world to keep the planet below the 2-degree threshold that scientists consider critical to Earth's well-being.

As soon as Modi returned from Paris in December, he called his cabinet secretaries together to develop proposals on efficiency improvements, according to Ajay Mathur, director general of The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), based in India.

Mathur says the most important program to come out of that effort aims to improve agricultural irrigation pumps, "which are notorious for their low efficiency."

Another aims to make air conditioners more efficient, a key effort, Mathur says, because "one of the largest growth areas in energy in India is the air conditioning sector."

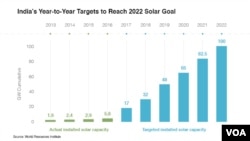

In 2014, Modi set a target of 100 gigawatts of solar generating capacity by 2022 — an extremely ambitious goal considering that the entire world's capacity that year was 177 GW, and India had 2.4 GW.

The government has approved 15 GW of new capacity this year. But the long-term goals look harder to reach.

"What India needs is finance," Light said. "With some 240 million people not having access to electricity now, India essentially has the biggest single-country electricity market in the world. This is a huge investment opportunity."

But investors have not been eager to dive into India's complicated business environment. U.S. and Indian government efforts are "way too small to tackle this incredibly critical and important problem, and progress on them has been very slow," Light noted.

Increase in coal

At the same time, India plans 290 GW of new coal-fired capacity by 2030, according to a Climate Action Tracker report, a huge setback for global greenhouse gas emissions.

"The question with fighting climate change has never been, 'Are people going to start using solar power?'" said Oren Cass, energy policy researcher at the Manhattan Institute. "It's been, 'Can you persuade the developing world to not build new fossil fuel power?'"

Given the rate that electricity demand is expected to grow in the developing world, Cass says the answer is almost certainly no. By 2040, power generation in non-OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries will be more than twice what it was in 2011, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

"The growth in renewables doesn't get you anywhere close to leveling off growth in fossil fuels, let alone reducing [it]," he said.

Besides, Cass says, India has not pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. It only pledged to reduce the intensity of its emissions per unit of GDP, which, Cass notes, is happening anyway.

In contrast, he adds, "The United States has now committed to making very dramatic and costly emissions reductions ... in return for getting nothing from other countries."

Cass considers the Paris agreement a "disaster" because it "let everybody else off the hook."

Paris agreement

The Paris agreement goes into effect when 55 countries representing 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions ratify it. The world's two largest emitters, the United States and China, have announced they will do so by the end of the year. Several other emitters have, as well. If India joins, that would push the total over the 55 percent threshold.

Democratic presidential front-runner Hillary Clinton has praised the Paris agreement, but presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump says he would cancel it.

"The Paris agreement doesn't do nearly enough," said Niven Winchester, climate economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. However, he says, Paris is a starting point. "If nations can't agree to the Paris agreement, there's no way we're going to meet the 2-degree target."

But Winchester says that if India does ratify it, then India's allies would be more likely to follow, kicking off a "snowball effect."

Obama also told reporters the talks focused on progress toward civil nuclear energy accords. "I indicated our support for India becoming a part of the Nuclear Suppliers Group," he said.

The NSG is a multinational body that seeks to control the export and re-transfer of materials that may be applicable to nuclear weapons development. It also seeks to improve safeguards and protection on existing materials.