Four-wheelers putter along the main road in Moapa Valley, Nevada, and the whimper of a horse carries from a nearby field. “Gateway to the Valley of Fire,” the town’s chamber of commerce calls it because of Moapa Valley’s proximity to the red sandstone walls of nearby Valley of Fire State Park. The town’s 7,000 residents are 92 percent white.

Moapa Valley could be said to be emblematic of the old Nevada, where a silver lode was discovered in 1859 bringing white settlers to carve out livings in the desert.

“We don’t seem to have the same identity that we had as Nevadans even 10 years ago,” laments Ken Staten, a registered Republican from Moapa Valley.

Staten was referring to Nevada’s changing demographics, which can be attributed to an influx of both Californians and immigrants.

With its tensions between rural and urban voters, new demographics versus old ones, Nevada is one example of what is happening to U.S. politics on a national level.

For example, Mark Hugo Lopez, Director of Global Migration and Demography Research at Pew Research Center, says Republican-friendly states Georgia, Texas and North Carolina, may eventually be in play politically because of growing Hispanic populations.

In Nevada, most fingers point to California. Nevadans say their state is becoming “California-cated,” “California-fied,” or some variation. Lured by low tax rates and a jobs boom in construction and tourism, many Californians are flocking to the Silver State.

But “Californians bringing their Californian problems” has long been a common refrain in surrounding states, says Lopez. The question is, “Which Californians are leaving?”

While recent immigrants make up a large share of Latinos in Nevada, “out-migration from California to Nevada has had a lot of Latinos as a part of it,” Lopez said.

As a result, Nevada is increasingly Latino.

“[Immigrants] come here, and all it is, is a freebie,” said Lyle Kump, a Moapa Valley retiree who worries about the prospect of Nevada towns becoming “sanctuary” spaces for undocumented immigrants. “If they build the wall, I hope they continue it right up along the border of California.”

The new Nevada

Only 96 kilometers from Moapa Valley, limousines pull up to mega hotel-casinos in Las Vegas. The city has 10 times the population of the town and it is only 48 percent non-Hispanic white. The rest is a basket of racial identities.

In Clark County, home to Las Vegas and more than two million of the state’s three million residents, students speak more than 150 languages.

Here, diversity is a source of pride, even to Republicans whose party is led by anti-immigrant President Donald Trump.

“Las Vegas is truly unique,” remarked West Allen, an attorney and community leader at his local Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. “My children go to school with people from Russia, from Mexico, from China, almost anywhere in the world.”

In Allen’s view, immigrants enrich the country overall, and contribute to what he describes as Las Vegas’ deeply spiritual community that looks out for each other.

“We want people who are the best people from every nation to become Americans,” Allen said.

Changing population, changing votes?

In 2016, Las Vegas swung Nevada’s overall vote for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, while at the other end of Clark County, Moapa Valley voted 78 percent for Trump.

Latinos helped give the state to Clinton, choosing her over Trump by a nationwide margin of 66 to 28. It was the third consecutive presidential race in which Nevada voted blue.

Before that, the state was reliably Republican, or red.

In midterm election years, like this one, Nevada tends to be purple, electing a mixed bag of congressional candidates.

The changes in voting track the changes in demographics and have led to the assumption that Nevada will become a blue state.

Sherman Avery, a Republican Jamaican-American coffee shop owner in the affluent community of Summerlin, in the Las Vegas area, supports what he calls “an orderly flow” of immigrants but calls the political transformation of his state “kind of sad.”

“If you look at the history of Nevada — Las Vegas — it was made by people who had a pioneering spirit,” Avery said. “It wasn’t made by people who said, ‘Gimme, gimme, gimme,’ entitlement programs, all that kind of stuff.”

But will they vote?

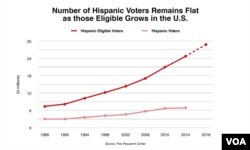

Latinos are now 19 percent of Nevada’s eligible voters, according to the Pew Research Center.

If they turn out in large numbers, Hispanics could sway the closely fought battle between incumbent Republican Senator Dean Heller and his democratic challenger, Jacky Rosen, a house member.

Yet, history says a vast majority of them may not vote at all. Hispanic participation in midterm elections, Pew says, has declined over the past decade and reached a record low in 2014, the last midterm election. Just 16 percent of Latino voters ages 18 to 35 cast a ballot, less than half the rate of Latinos aged 36 and older (36.2 percent) and nearly one-third that of white voters overall (45.8 percent).

But there are more younger Latinos; they make up almost half of eligible Latino voters. So their lack of enthusiasm for voting has an outsize effect.

The relative youth of Hispanics is also seen as closing the voting gap gradually.

“We’re going to continue to push,” to get Hispanics to vote, said Alicia Contreras, interim Nevada state director for the civic engagement organization Mi Familia Vota. “It does take a village, and here in Nevada that is exactly the model that we work on.”

How the new Hispanic population will vote is also not assured. Midterm elections have shown mixed results for Democratic congressional candidates among Latino and Hispanic voters.

Republicans in Nevada plan to stick with moderate messaging and conservative, family-centric principles.

“Although the voting is different demographically, the values haven’t changed very much.” Las Vegas attorney Allen observed.

“You’re not going to win them over by just telling them, ‘You’re wrong,’” said Summerlin’s Sherman Avery. “They can see it in your life, and they can see you moving forward.”