It’s disinterest. It’s selfishness. It’s preoccupation with avocado toast.

For Americans under 30 — who only recently became the largest voting bloc in the U.S. and are oft-maligned for lack of civic participation — the largest barrier to voting might be 3.9 square centimeters (0.6 square inches) of aging technology.

“The ‘finding-a-stamp thing’ is sometimes considered a joke, but a lot of young people have never had to mail anything because everything is done online,” said Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts.

“Or they have nice parents who have done everything for them,” she added.

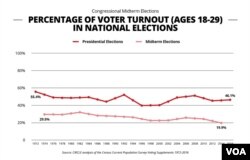

College students and young adults comprised 30 percent of eligible U.S. voters in 2016, but only half of them showed up on Election Day. A slightly bigger turnout of younger voters in a handful of battleground states could have altered the outcome of the 2016 presidential election. Instead, Gen Xers — ages 36 to 51 — combined with Baby Boomers — ages 52 to 70 — drove the political agenda with their votes.

Our youngest voters are transitional by design, moving from the reliability of their parents’ home to a series of change-of-address cards that continues long after graduation for many.

“Young people don’t begin to vote until their lives basically settle in one place and get some stability,” said Kawashima-Ginsberg. “When you ask why they don’t vote, especially from less affluent backgrounds, they tend to report more barriers.”

Small but significant barriers are often overlooked by complaining elders. In addition to moving each year, younger voters might not have a car or other transportation to the polls, Kawashima-Ginsberg explained, and that poll might be hours or time zones away if the voter is registered at their parents’ out-of-state address.

Other young voters might be afraid to ask for time off from work to vote, especially if they are hourly workers. Unfamiliarity with polling places such as schools or community centers might be just enough a hurdle to make a voter shrug off Election Day. And not every young person has a driver's license or other essential identification acquired through birth certificates and other legal documentation typically kept safe by parents.

Absentee ballots, too, are not always user-friendly to students born into a generation that has always enjoyed the ease and efficiency of online transactions.

“Many of our students are tech-savvy and are more used to Amazon,” the behemoth, online shopping site that can facilitate transactions in one click, said Alison Nabatoff, a program officer in the Office of the Dean of Undergraduate Students at Princeton University. “Going to paper is a challenge.”

Madeleine Marr, a sophomore at Princeton University from suburban Philadelphia, laments the process.

“While there has been a vocal criticism of college students for our historically low voter turnout rates, not much attention has been paid to how difficult it is for college students to actually get their ballots to the voting box,” Marr writes in the Daily Princetonian.

“It is important that college students increase their voter turnout, yet absentee voting is antiquated and prevents college students from fully participating in the electoral process.”

Absentee voting differs from state to state. Procrastinators take note: Most states require the ballot be received — not just postmarked — by Election Day. The ballot request varies state to state, according to Vote.org, from 21 days before the election to one day before.

Some states allow balloting by fax. (That is an electronic transmission that might be as familiar to younger voters as the telegraph is to middle-age voters.) And while you can register to vote online, you cannot cast a vote online unless you are out of the country and fall within the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). But that process is not without barriers, either, and states have increasingly expressed concern with the security risk of voting online.

“The idea of conducting elections entirely via the internet is not something states are considering now or in the near future,” according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Some voting factors are typical of every generation, not just Millennials. What usually sparks investment in the civic process is graduating from college, getting married, having a child, and buying — not renting — property, Kawashima-Ginsberg said.

But many Millennials lament having to postpone some of those lifetime milestones, unlike their Baby Boomer parents and grandparents. As a consequence, many feel less of a connection to local and national politics and issues.

“Our total debt for credit cards and student loans combined is almost $150,000,” said Matt Porter, 32, who lives with his fiance in Lowell, Massachusetts. “It’s absolutely insane and makes it really hard to move forward with life goals.”

Because the average cost of an undergraduate degree from a college and university has risen $63,973, or roughly 161 percent since 1987, many young people say they can’t afford a mortgage while paying off student debt. Some say they feel they cannot afford marriage or children, either, while they are paying student loans, nevermind a monthly mortgage.

“College graduates will be saddled with so much debt that many will have less purchasing power to afford homes, and may significantly delay marriages and childbearing,” wrote Brialle D. Ringer in the McNair Scholars Research Journal at Eastern Michigan University in 2015.

While those obstacles might hold young people back from the polls, recent social issues that affect their generation — like gun violence and climate change — can be drivers. Although young people are often accused of “slacktivism,” for engaging online but not in person, that criticism is not quite warranted, Kawashima-Ginsberg said.

Young people are responding to those issues through voter participation, said Kawashima-Ginsberg. CIRCLE’s recent polling found that 34 percent of young people ages 18 to 24 are “extremely likely” to vote in the midterms. A poll by Harvard’s Institute of Politics say that number is closer to 40 percent, “with 54 percent of Democrats, 43 percent of Republicans and 24 percent of Independents considered likely voters.

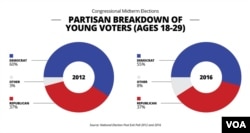

“As young Republicans have become more engaged, the preference among likely voters for Democrats to control Congress has decreased from a 41-point advantage in the IOP April 2018 poll to a 34-point lead today," according to a summary of the poll.

Voters 18 to 21 who were not yet eligible to vote in 2016 said they were extremely likely to cast ballots this election cycle.

And that, in part, is because of high schoolers from Parkland, Florida, who survived a mass shooting in February, and organized a march on Washington a month later that drew 200,000 participants and sparked a voter registration campaign nationwide targeted to new voters.

“Young people who report being actively engaged with the post-Parkland movement for gun violence prevention are even more likely (50 percent) to say that they’re extremely likely to vote,” Kawashima-Ginsberg said.