Climate change, deforestation, and urbanization are some of the major risk factors behind the increasing number of outbreaks of viruses such as dengue, Zika, and chikungunya around the world, warns a study by the World Health Organization.

The study says the incidence of infections caused by these mosquito-borne illnesses, which thrive in tropical and subtropical climates, have grown dramatically in recent decades. The report says cases of dengue have increased from just over half a million globally in 2000 to 5.2 million in 2019.

And the trend continues. The latest data show about half of the world’s population now is at risk of dengue, the most common viral infection that spreads from mosquitoes to people, with an estimated 100 to 400 million infections occurring every year.

“Right now, around 129 countries are at risk of dengue, and it is endemic in over 100 countries,” said Raman Velayudhan, unit head of WHOs global program on control of neglected tropical diseases coordinating dengue and arbovirus initiative.

He said dengue in South America alone is moving further south to countries such as Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay.

Climate change gives rise to increased precipitation, higher temperatures and higher humidity, conditions under which mosquitos thrive and multiply. There is new research, which shows that even dry weather enables mosquitos to breed. Scientists say dry weather makes mosquitos thirsty and when they become dehydrated, they want to feed on blood more often.

“This is really worrying because this shows that climate change has played a key role in facilitating the spread of the vector mosquitoes down south. And then when people travel, naturally the virus goes along with them,” he said. “And this trend is likely to continue for the rest of the world.

“We have already got reports from Sudan, which has recorded a quite high increase in dengue cases, over 8,000 cases and 45 deaths since July.”

WHO officials note that cases of dengue in Asia have increased in Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Dengue is a mild disease, in most cases. While most people will not have symptoms, some might experience high fever, headache, body aches, nausea, and rash. Most people will recover in a couple of weeks, but dengue could be fatal for those who develop severe cases.

“This is a big threat to the world because most of the countries now have all the four related dengue viruses in circulation,” Velayudhan said. “Dengue unfortunately does not have a treatment and even vaccines are just emerging in the market right now,” he said.

He noted that one vaccine, found to be effective in people who have had dengue once, is licensed in about 20 countries, two other vaccines are in the pipeline, and two drugs are under development.

Chikungunya and Zika

The Chikungunya virus is spread by Aedes mosquitoes and is found on nearly all continents. To date, about 115 countries have reported cases. The disease can cause chronic disabilities in some people and severely impact their quality of life.

Diana Rojas Alvarez, WHO technical lead for Zika and chikungunya and co-lead of the global arbovirus initiative said that cases of chikungunya in the Americas have increased from 50,000 in 2022 to 135,000 this year. She said the virus was circulating out of the usual endemic areas inside South America and was spreading into other regions.

Arboviruses are spread by arthropods – which include mosquitos, ticks, centipedes and millipedes and spiders.

“Now we are seeing transmission where we did not see it before. The countries where the mosquito has been introduced is increasing and where the mosquito is established is alarming,” she said.

“We should be prepared to detect some cases during spring and summer in Europe and in the northern hemisphere, also in southeast Asia because the arbovirus season starts later there. It is usually when the summer season starts,” Rojas Alvarez said.

Like dengue and chikungunya, the Zika virus is spread by the Aedes mosquitoes, which mostly bite during the day. However, unlike the other two viruses, Zika also can be transmitted sexually between people and from mother to child during pregnancy.

Between October 2015 and January 2016, Brazil reported 1.5 million people were infected with the Zika virus and more than 3,500 babies were born with smaller heads than normal—a condition known as microcephaly.

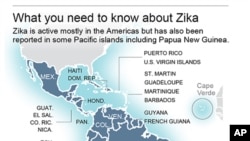

The epidemic spread to other parts of South and North America and several islands in the Pacific. The WHO declared Zika a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in February 2016.

“Zika is still circulating,” said Rojas Alvarez. “Of course, we went from millions of cases in 2015 and 2016 and since 2017 the cases are going down, but we still have about 30 to 40,000 cases reported every year, mostly in the Americas.”

She added that 89 countries and territories have reported cases of Zika virus transmission.

Last year, WHO launched the Global Arbovirus Initiative to tackle emerging and re-emerging arboviruses with epidemic and pandemic potential. The plan focuses on preparedness, early detection, and response to outbreaks, as well as the development of new drugs and vaccines.

While these strategies take shape, health officials are urging communities to eliminate mosquito breeding sites in and around homes and use mosquito repellent to protect themselves against the potentially fatal diseases.