A senior official of the Texas hospital system that treated a Liberian national with Ebola said on Thursday "we made mistakes" in diagnosing the man who later died and in giving inaccurate information to the public, adding that he was “deeply sorry.”

Dr. Daniel Varga, chief clinical officer and senior vice president of Texas Health Resources, also said there was no actual Ebola training for staff before that first patient, Liberian Thomas Eric Duncan, was admitted.

Varga's remarks were part of his prepared statement for a House congressional hearing in the United States, where lawmakers grilled the nation's top medical experts to discuss Ebola detection and control measures. Varga did not attend the hearing, instead remaining in Texas.

Ebola treatment protocols have come under scrutiny since two Texas health care workers contracted the disease after caring for Duncan, who was hospitalized and died earlier this month in Dallas, Texas.

Patients transferred

One of the women, nurse Nina Pham, 26, is to be flown to the National Institutes of Health isolation unit in Bethesda, Maryland. While the second, nurse Amber Vinson, 29 - who took a domestic flight right before her diagnosis - was flown Wednesday from Dallas to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, where two other Ebola patients were successfully treated.

Speaking at the hearing Dr. Thomas Frieden, head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said he worries that the spread of Ebola virus in West Africa will pose a long-term threat to the U.S. health care system.

Frieden said the Ebola threat will best be countered by strengthening health care systems and training health care providers.

He acknowledged, however, that there is not yet an effective vaccine for the disease but said he remains confident that Ebola is not a "significant public health threat" in the United States.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told lawmakers that work on two Ebola vaccines was in Phase 1 of clinical trials to determine their safety and effectiveness.

“If those parameters are met, we will advance to a much larger trial in larger numbers of individuals to determine if it is actually effective, as well as not having a paradoxical, negative deleterious effect,” Fauci said.

“The reason we think this is important is that if we do not control the epidemic with pure public health measures, it is entirely conceivable that we may need a vaccine and it's important to prove that it is safe and effective,” he added.

WHO seeks to stop spread

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization said it is sending teams to Mali and Ivory Coast to evaluate the countries' Ebola-preparedness measures at their shared borders with Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The WHO's health security response chief, Isabelle Nuttall, told reporters Thursday that a team of 10 people will leave for Mali on Sunday and another will leave for Ivory Coast within days.

Nuttall said the key to stopping the spread of Ebola lies in controlling its spread in the three West African nations hardest-hit by the disease.

She said this makes "exit screening" at the borders of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone very important.

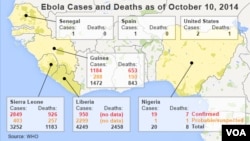

The World Health Organization said Nigeria and Senegal appear to have snuffed out the virus.

Nigeria was able to use an emergency command center that was built by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to combat polio.

Senegal, health officials say, did well in finding and isolating a man with Ebola who slipped across the border from Guinea in August. The World Health Organization says on Friday it will declare the end of the disease in Senegal if no new cases surface.

Authorities in some African countries have used tight air travel restrictions, tougher than those contemplated by the U.S. or British governments, to stop the spread of the virus.

South Africa and Zambia slapped travel and entry restrictions on Ebola-stricken countries. Kenya Airways, the country's main airline, stopped flying to the affected lands.

In Zimbabwe, all travelers from West Africa are put under 21-day surveillance. Health officials regularly visit those travelers to check their condition.

Nigeria initially banned flights from countries with Ebola but relaxed the restriction once it believed that airlines were competent to take travelers' temperatures and follow other measures to prevent people with Ebola from flying.

Nigeria has teams taking the temperature of travelers at airports and seaports.

In Ethiopia, the main international airport in Addis Ababa screens all arriving passengers, including those from Europe and the U.S. Ethiopia is using body scans to check people for fevers.

European health ministers gathered in Brussels for high-level talks on how to screen for the Ebola virus at European borders and airports. France said that on Saturday, it will begin screening passengers who arrive at Paris' Charles de Gaulle airport on the once-daily flight from Guinea's capital.

In the past week, new screening measures have been put in place at five U.S. airports. Those airports, all in major cities, receive most of the incoming passengers from the West African nations at the center of the outbreak.

Against travel ban

Obama remains opposed to imposing a ban on travel from the Ebola-afflicted nations of West Africa. The president also said he may appoint an official to deal with efforts to fight the disease in the United States.

Pressure has been building on President Obama to do more to prevent Ebola from spreading in the United States.

Critics say the administration has not done enough to prevent the spread of Ebola and have called for the U.S. to impose a travel ban on people coming from Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

After meeting with members of his Ebola response team at the White House late Thursday, the president indicated he remains opposed to such a ban.

“I don’t have a philosophical objection, necessarily, to a travel ban if that is the thing that is going to keep the American people safe. The problem is that in all the discussions I’ve had thus far with experts in the field, experts in infectious disease, is that a travel ban is less effective than the measures that we are currently instituting,” said Obama.

Those measures include screening passengers before they board airplanes in West Africa and screening them again when they arrive in the United States. Their addresses are kept on file to make sure health officials can track them.

Obama said a travel ban would increase the likelihood of people evading the system and slipping into the country undetected.

The U.S. leader said the best way to prevent a major outbreak is by keeping up efforts in West Africa.

“The most important thing that I can do for keeping the American people safe is for us to be able to deal with Ebola at the source, where you have a huge outbreak in West Africa,” said Obama.

Earlier Thursday, the president authorized the Pentagon to send national guard and reserve troops, if needed, to the region. The U.S. already has committed 4,000 troops to West Africa to help afflicted countries combat the epidemic.

The Pentagon said it had no immediate plans to send reservists or National Guard troops to Africa. It said the order simply allows the military to begin planning for those forces in its overall response.

Responding to domestic pressure, the U.S. leader said it may be appropriate to appoint an official, or czar, to lead the U.S. response to Ebola.

Nearly 4,500 people have died from the virus since the outbreak began late last year. The virus causes fever, bleeding, vomiting and diarrhea, and spreads through contact with an infected person's bodily fluids.

VOA correspondents Luis Ramirez and Kells Hetherington contributed to this report. Some material for this report came from Reuters and AP.