Beijing residents no longer need a negative COVID-19 test to enter grocery stores, offices, airports and parks, as China relaxes its strict zero-COVID policy after an unprecedented display of civil disobedience erupted in cities across China last month.

More steps to ease the policy are expected in the coming days.

Thousands of Chinese in more than 20 cities took to the streets beginning on November 25, frustrated by lengthy COVID-19 lockdowns, widespread testing and other restrictions placed on people's movements. It was one of the largest acts of public dissent in China in decades.

While most of the protesters focused their anger on the government's COVID-19 policies, some also demanded the resignation of President Xi Jinping. The government considers such speech subversive.

Though government officials did not publicly mention the protesters, they suggested easing restrictions within days of the first protests to head off any more demonstrations.

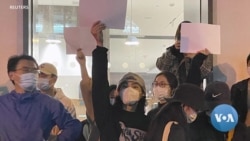

Blank paper

Videos of protesters across the country captured demonstrators raising blank sheets of paper, a quiet show of dissent and a tactic used to evade censorship and prosecution.

“Under high political pressure and danger, people don’t say the words, but they understand each other. When seeing other people on the streets, they know what we want to say with just a look,” Yang Jianli, a human rights activist and founder of Washington, D.C.- based Initiatives for China, told VOA.

“It’s all revealed on the white paper. It’s very expressive, easily spread, with low risk and cost. That’s why it was used by many protesters,” Yang added.

Perry Link, professor emeritus of East Asian studies at Princeton University and distinguished professor of comparative literature at the University of California, Riverside, told VOA that the spectrum of protesters’ frustrations — from COVID-19 restrictions to calling for Xi’s resignation — is symbolically contained on the blank paper.

"It's those very fundamental complaints that [protesters] can't say. It's very dangerous to stay something like 'Down with the Communist Party,'" Link said.

He said the blank paper is defensive because it lets protesters deny they are saying anything negative about the government, and offensive because the actual message is created in the mind of the viewer.

"It's especially articulate in the sense that it lets the reader infer the meaning," Link said.

China's government has a complex system of censorship and maintains a tight grip on the country's internet. It bans almost all foreign news and social media and immediately deletes material on webpages and domestic social media platforms that the Communist Party deems offensive.

Origins

After more than three years of strict COVID-19 restrictions, discontent had been brewing for months across China, with sporadic protests breaking out in cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai.

However, it was a deadly apartment fire in Xinjiang's regional capital, Urumqi, in late November that triggered the recent national protests.

Protesters said the victims in the burning building were unable to escape because of locked doors and other infection controls. Chinese officials have denied the doors were locked and blamed "forces with ulterior motives" for linking the fire to the COVID-19 measures.

A witness to the blaze told VOA that firefighters had difficulty entering the building because of the government's anti-COVID policies.

Crackdown

The recent demonstrations were quickly met by a large police presence and led to the arrests of an unknown number of people.

A Shanghai resident who participated in the first vigils to commemorate those who died in the Urumqi apartment fire told VOA he saw police arresting multiple people.

When asked why he participated in the vigil, he said, "I happened to see it and felt that I had to participate because this is my responsibility as a citizen."

Since the protests, police have been patrolling the streets of major Chinese cities to head off any more demonstrations. Notes on social media said people were being stopped randomly by police who checked their phones, possibly looking for signs they were supporting the protests.

Policy change

Following the protests, officials across the country announced at least some changes to their COVID-19 protocols and restrictions.

Shanghai announced it would remove COVID-19 testing requirements to enter most public places beginning on Tuesday.

Commuters in Beijing and other Chinese cities were allowed Monday to board buses without a negative COVID-19 test in the past 48 hours.

Despite Chinese officials signaling a shift in policy, many of the COVID-19 restrictions are still in force. It remains to be seen whether the government moves will go far enough to appease those frustrated by lengthy lockdowns and widespread testing.

What’s next?

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman said at an American University event in Washington last week that the protests across China were effective.

"I think we have seen the protests die down now in China, and the reason they've died down is they actually had an effect," she said.

Link agreed that the protests had an effect in changing government policy but said government officials "stamped out" the demonstrations.

"The repression system is so granular in China. It's right down to the neighborhood level, where plainclothes police know who you are, and talk to you, and persuade you. And if you are not persuaded, then they threaten you. And if you are not threatened, then they arrest you," he said.

"It's an immense system, and it's very effective. … I do think that system will snuff out" further protests.

Some information in this report came from Reuters and The Associated Press. VOA’s Mandarin Service contributed to this report.