WASHINGTON, DC —

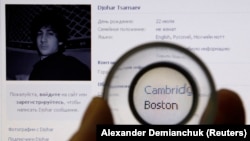

National security specialists often say the hardest terrorist to track down is the one who acts alone, who is not a member of a terrorist group like al-Qaida. President Barack Obama said much the same thing recently when he referred to alleged Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev as a self-radicalized “lone wolf” terrorist.

“Lone wolves” may not have killed as many people as al-Qaida did one day 12 years ago in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, but they have terrorized a lot of Americans.

Timothy McVeigh is one example. He killed 168 people when he bombed a federal office building in Oklahoma City 18 years ago. Another is Ted Kaczynski, the so-called “Unabomber” who killed three and wounded 23 more in various parts of the United States over a 17-year period ending in 1995. McVeigh considered the federal government tyrannical, and Kaczynski apparently felt the same way about just about everything in the modern world.

Keying off last month’s Boston Marathon bombing, al-Qaida’s online magazine, Inspire, predicts that the number of lone wolf terror attacks will increase and calls on Muslim youths in the West “to awake the American people from their long slumber” and “serve them drinks in the same cup we [Muslims] drink from, the cup of wars and battles, explosions and assassinations, deaths and injuries.”

Since al-Qaida’s 2001 strikes in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, authorities have reported more than 50 terror attacks in the U.S. alone. So who are these terrorists and what drives them to violence?

Common traits

The lone wolf terrorist is generally understood as an individual acting apart from any organized group to commit acts of political violence. While no fixed psychological profile has been established to explain the lone actor, Bryn Mawr College psychology professor Clark McCauley says research demonstrates some common traits shared by most lone wolves.

Nearly all of them have personal and/or political grievances, the perception that harm has been done to them or to society, McCauley says. One of the most notorious examples is Kaczinski, the so-called Unabomber, who believed that technology was destroying both the environment and humanity.

McCauley cites the more recent example of the Boston marathon bomber: “He had great ambitions and hopes of making his way as a boxing champion and turning pro. And then he was, in his opinion, unjustly blocked from this ambition by new rules that said that only citizens…could compete in the Golden Gloves championships.”

Lone wolves may have become “unfrozen,” McCauley explains, a psychological term for the process of disconnecting from loved ones, work and daily routines that might otherwise anchor them against radicalization. They may suffer from depression or other mental disorders.

“Tsarnaev’s parents moved to Dagestan. His younger brother, with whom he was pretty close, moved off to college, and he had no way to support himself,” McCauley said. “So the would-be boxing champion was reduced to delivering pizzas, occasionally. Meanwhile, he’s got a wife, a child, and his wife is providing most of the regular income to support the family, and this is a very uncomfortable and even humiliating situation for a young man from a traditional background to be in.”

McCauley said Lone Wolves may also see violence as the ticket to gaining love or respect. Tsarnaev traveled to Dagestan, where he hoped to join the jihadists as a means of proving himself.

“Then he gets brushed off by the militants, who suspect probably that he’s not to be relied upon,” McCauley said. “And now what is he going to do? He’s got no way to advance in status…his only remaining alternative is to go back and mount an attack in the U.S.”

Looking for approval

Thomas “T.J.” Leyden is a former American neo-Nazi who says he grew up in a violent home, where he received little attention from his father.

“The first time my dad ever told me he loved me was after I beat one of my cousins up really severely,” he told VOA. “So when my parents got divorced, I started hanging around on the street, and there was this group of these skinhead guys, and the more violent I was … the more affection they showed me. It was a perfect extension of my father’s love. So I started adapting their philosophies of ‘You gotta be bad; you gotta be tough.’”

Leyden joined what was then largest and most violent neo-Nazi group in the U.S. While a member, he also joined the U.S. Marine Corps, where he says he learned recruiting skills that he could apply to life as a skinhead.

“I rose through the ranks and eventually became a regional recruiter. The Marines had taught me organizational skills, leadership ability and recruitment techniques. It’s a system called ‘tear down and rebuild.’ You know, you destroy a kid’s self-esteem, and then as a kid does right, you praise him, you glorify him, give him all the praise in the world and, I mean, that kid will do anything for you.

Tawfik Hamid is Senior Fellow of Radical Islamic Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. Thirty years ago, as a university student in Egypt, Hamid was recruited into the radical Islamic group, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya. For him, religious faith made him invulnerable.

“And at that time, there was a wave of Islamic revival throughout the country. We used to think that even our economic problems, the traffic—all the problems that the country was suffering from—we would become rich like Saudi Arabia if we would apply Sharia.”

Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya encouraged him to join up, flattering him for his ability to recite the Quran. “You are elected, you will be with a powerful group--at that time, the more religious you were, the more respect you won--and so you are moving in a wave to change the world and everyone is encouraging you…You feel like God.”

After two years, Hamid, disillusioned, left the group and later turned against it.

Lone Wolves: Few and far between

The lone wolf is particularly effective because he keeps to himself, and law enforcement may not even be aware of his existence. Because he does not belong to a group, his communications are less liable to be monitored. All of the information the lone wolf needs to plan an attack – from bomb making to travel planning -- is readily available on the internet.

Lone wolf terrorism is cost effective. It reportedly cost Tamerlan Tsarnaev only $400 to implement the Boston bombings.

The lone wolf also is unpredictable—he or she can strike at any time. And while the attacker may be inspired by the ideology of a radical group, the group itself is not directly implicated.

But security experts caution the public against being overly fearful of would-be lone world terrorists. The good news, they say, is that the rise in lone-wolf terrorism signals that organized jihad is failing. Further, they say the lone wolf is a rare phenomenon. While some individuals may dream of taking violent action, few individuals possess the skill, discipline and patience to actually follow through on such attacks.

“Lone wolves” may not have killed as many people as al-Qaida did one day 12 years ago in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, but they have terrorized a lot of Americans.

Timothy McVeigh is one example. He killed 168 people when he bombed a federal office building in Oklahoma City 18 years ago. Another is Ted Kaczynski, the so-called “Unabomber” who killed three and wounded 23 more in various parts of the United States over a 17-year period ending in 1995. McVeigh considered the federal government tyrannical, and Kaczynski apparently felt the same way about just about everything in the modern world.

Keying off last month’s Boston Marathon bombing, al-Qaida’s online magazine, Inspire, predicts that the number of lone wolf terror attacks will increase and calls on Muslim youths in the West “to awake the American people from their long slumber” and “serve them drinks in the same cup we [Muslims] drink from, the cup of wars and battles, explosions and assassinations, deaths and injuries.”

Since al-Qaida’s 2001 strikes in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, authorities have reported more than 50 terror attacks in the U.S. alone. So who are these terrorists and what drives them to violence?

Common traits

The lone wolf terrorist is generally understood as an individual acting apart from any organized group to commit acts of political violence. While no fixed psychological profile has been established to explain the lone actor, Bryn Mawr College psychology professor Clark McCauley says research demonstrates some common traits shared by most lone wolves.

Nearly all of them have personal and/or political grievances, the perception that harm has been done to them or to society, McCauley says. One of the most notorious examples is Kaczinski, the so-called Unabomber, who believed that technology was destroying both the environment and humanity.

McCauley cites the more recent example of the Boston marathon bomber: “He had great ambitions and hopes of making his way as a boxing champion and turning pro. And then he was, in his opinion, unjustly blocked from this ambition by new rules that said that only citizens…could compete in the Golden Gloves championships.”

Lone wolves may have become “unfrozen,” McCauley explains, a psychological term for the process of disconnecting from loved ones, work and daily routines that might otherwise anchor them against radicalization. They may suffer from depression or other mental disorders.

“Tsarnaev’s parents moved to Dagestan. His younger brother, with whom he was pretty close, moved off to college, and he had no way to support himself,” McCauley said. “So the would-be boxing champion was reduced to delivering pizzas, occasionally. Meanwhile, he’s got a wife, a child, and his wife is providing most of the regular income to support the family, and this is a very uncomfortable and even humiliating situation for a young man from a traditional background to be in.”

McCauley said Lone Wolves may also see violence as the ticket to gaining love or respect. Tsarnaev traveled to Dagestan, where he hoped to join the jihadists as a means of proving himself.

“Then he gets brushed off by the militants, who suspect probably that he’s not to be relied upon,” McCauley said. “And now what is he going to do? He’s got no way to advance in status…his only remaining alternative is to go back and mount an attack in the U.S.”

Looking for approval

Thomas “T.J.” Leyden is a former American neo-Nazi who says he grew up in a violent home, where he received little attention from his father.

“The first time my dad ever told me he loved me was after I beat one of my cousins up really severely,” he told VOA. “So when my parents got divorced, I started hanging around on the street, and there was this group of these skinhead guys, and the more violent I was … the more affection they showed me. It was a perfect extension of my father’s love. So I started adapting their philosophies of ‘You gotta be bad; you gotta be tough.’”

Leyden joined what was then largest and most violent neo-Nazi group in the U.S. While a member, he also joined the U.S. Marine Corps, where he says he learned recruiting skills that he could apply to life as a skinhead.

“I rose through the ranks and eventually became a regional recruiter. The Marines had taught me organizational skills, leadership ability and recruitment techniques. It’s a system called ‘tear down and rebuild.’ You know, you destroy a kid’s self-esteem, and then as a kid does right, you praise him, you glorify him, give him all the praise in the world and, I mean, that kid will do anything for you.

Tawfik Hamid is Senior Fellow of Radical Islamic Studies at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. Thirty years ago, as a university student in Egypt, Hamid was recruited into the radical Islamic group, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya. For him, religious faith made him invulnerable.

“And at that time, there was a wave of Islamic revival throughout the country. We used to think that even our economic problems, the traffic—all the problems that the country was suffering from—we would become rich like Saudi Arabia if we would apply Sharia.”

Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya encouraged him to join up, flattering him for his ability to recite the Quran. “You are elected, you will be with a powerful group--at that time, the more religious you were, the more respect you won--and so you are moving in a wave to change the world and everyone is encouraging you…You feel like God.”

After two years, Hamid, disillusioned, left the group and later turned against it.

Lone Wolves: Few and far between

The lone wolf is particularly effective because he keeps to himself, and law enforcement may not even be aware of his existence. Because he does not belong to a group, his communications are less liable to be monitored. All of the information the lone wolf needs to plan an attack – from bomb making to travel planning -- is readily available on the internet.

Lone wolf terrorism is cost effective. It reportedly cost Tamerlan Tsarnaev only $400 to implement the Boston bombings.

The lone wolf also is unpredictable—he or she can strike at any time. And while the attacker may be inspired by the ideology of a radical group, the group itself is not directly implicated.

But security experts caution the public against being overly fearful of would-be lone world terrorists. The good news, they say, is that the rise in lone-wolf terrorism signals that organized jihad is failing. Further, they say the lone wolf is a rare phenomenon. While some individuals may dream of taking violent action, few individuals possess the skill, discipline and patience to actually follow through on such attacks.