This is the third and final part in a series on violent Islamist extremism in the United States.

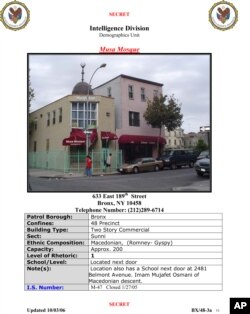

In 2003, the New York City Police Department created a secret surveillance unit that sent plainclothed officers into Muslim businesses, student associations, charities and mosques to spy on the Islamic community.

Fostered by a Central Intelligence Agency officer on detail to the NYPD, the “Demographics Unit” was to identify possible locations where a terrorist could melt into neighborhoods with high Muslim populations around the New York region.

The country was still feeling the aftershock of the 9/11 attacks and struggling to find its footing in the rapidly transforming landscape of counterterrorism.

According to an American Civil Liberties Union report, officers were told to engage in conversations with Muslim community leaders, students, and worshipers at mosques and Islamic associations to try to “gauge sentiment” about U.S. and foreign policy.

'Ancestries of interest'

They developed maps, took photographs and created a database of neighborhoods that had substantial numbers of people of 28 so-called “ancestries of interest.”

The result was a database mapping where Muslims lived, shopped, worked and prayed.

A 2011 expose of the program by The Associated Press prompted a fierce backlash, as well as two federal lawsuits that were eventually settled out of court.

During testimony, Assistant Police Chief Thomas Galati admitted that none of the information gleaned from the surveillance program had ever triggered an investigation.

“I never made a lead from rhetoric that came from the demographics report, and I’m here since 2006,” Galati testified in 2012 as part of a legal deposition. "I don’t recall other ones prior to my arrival.”

In 2014, newly elected Mayor Bill de Blasio closed the Demographics Unit.

Program's downside

But the idea of mass surveillance has not been abandoned.

After Islamic State (IS) attacks in Paris last November and the release of a video suggesting New York was next, presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump suggested the city restart the program.

This week, Trump again mentioned surveillance of mosques and Muslim communities after a man professing allegiance to IS went on a deadly rampage in Orlando, Florida. (Authorities are also looking into possible additional motives for the attack.)

“Law enforcement should really be focusing on criminal activity rather than ideology,” Faiza Patel, with the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, told VOA. “I think ideology is a kind of [an] attractive distracter. And the sort of really good old-fashioned police work is really what you need to uncover terrorist plots."

“Suppose the cops decided they would go after the Mafia by going into every Italian-American home in the city looking for evidence that someone in the family was working with the mob," Patel wrote in 2015. "The police motive is combating organized crime. But the method of achieving this objective — by targeting a particular ethnic group — violates the constitution’s equal protection guarantees.”

Patel said the program has had a chilling effect on the Muslim community in New York.

Mosques have traditionally been open and welcoming places for strangers. Now guests and newcomers are often treated with suspicion, she says, and everyone is looking over their shoulder.

“What we have seen and what has been documented is that people have stopped using mosques as being sort of the center of the community," she told VOA. "So they will go in and they will fulfill their religious obligation but then won’t hang around. They go home.”

As a result, the Muslim community is losing its ability to police itself, Patel said.

“The Muslim-American community has an excellent record of reporting to law enforcement when there are genuine concerns,” she said. “I think there is a study back in 2011 that found 40 percent of the terrorism plots that were foiled came from tips from the Muslim community.”

Strong families and communities

The experts VOA spoke with agreed that law enforcement has a critical role in countering extremism. But that role, they believe, should start when there is suspicion a crime is going to be committed.

They say a big part of the solution is strong communities and families – and empowering them to look after themselves. And they argue that surveillance and over-policing create a climate of fear and mistrust that make that impossible.

Mosques in the U.S. have traditionally had a variety of programs for young people and adults -- from after-school sports programs to classes on how to balance the family budget. It is in these settings where trust is built and a mentor can help a family dealing with a problem such as someone who might be expressing radical tendencies.

“You need to identify these (radical) people earlier,” said Seth Jones, a terrorism expert with the Rand Corporation. “So the question is, who has an influence and can have an influence in a positive way over these individuals?

"And it also has to do with families. Families in general are critical elements in bringing people back from crossing that radicalization line,” Jones added.

The FBI had Omar Mateen – the Orlando attacker – under surveillance for 10 months. Agents interviewed him three times, and they found no clues that led them to believe he would walk into a gay nightclub and kill 49 people.

But evidence is beginning to surface that his wife knew a plot was underway. She was reportedly with him as he scouted possible targets such Disney World resorts, a shopping mall and the Pulse nightclub, the scene of Sunday's killings.

Mateen's father and co-workers also expressed concerns about his behavior.

Family concerns

According to the FBI, in 50 percent of terrorism cases, a family member knew a relative was radicalizing but didn’t know what to do about it.

Anne Speckhard, a research psychologist and director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism, said rapid-intervention teams, alerted by emergency hotlines, can empower families and communities and be powerful tools for fighting extremism.

“Why would you call the FBI if they knew you were going to set up a sting operation? But you might call a hotline if you know they were going to send over a psychologist or an imam to talk to your kid – and say, 'You know what? You really got Islam wrong here,'” Speckhard said.