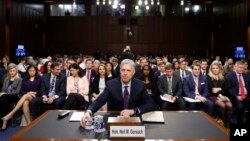

Lawmakers questioning Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch at his Senate confirmation are asking about something called "Chevron deference."

For the record, it is not about letting someone ahead of you in line at the gas station. But it is a legal concept Gorsuch has addressed as a judge on the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver since 2006.

What you should know about Chevron deference, and why it is such a big deal:

CHEVRON AND GORSUCH

The basic idea is that Congress writes laws that often aren't crystal clear. It leaves the details to federal agencies when it comes to things such as environmental regulations, workplace standards, consumer protections and even immigration law.

The Supreme Court's 1984 ruling in Chevron v. NRDC says that in those situations, often murky, courts should rely on the experts at the Environmental Protection Agency and other agencies to fill in the gaps. The opinion by Justice John Paul Stevens has been cited more than 15,000 times.

Gorsuch is part of a growing conservative legal movement that questions the idea that judges should essentially step aside and let the agencies have their way. He has written favorably about a big change in the law that would give judges more power and potentially make it harder to sustain governmental regulations.

Writing in a case involving immigration law last year, Gorsuch noted that court decisions "permit executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power and concentrate federal power in a way that seems more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers' design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth."

That view seemed to pick up support from Justice Samuel Alito when he spoke to a conservative group in Southern California in early February. Alito pointed to "a massive shift of lawmaking from the elected representatives of the people to unelected bureaucrats" that is a product of the high court's willingness to give regulators wide latitude.

Justice Clarence Thomas also is skeptical of the Chevron decision's validity.

THE PARTISAN DIVIDE

This kind of talk from Supreme Court justices and appellate judges worries advocates for regulation of business practices across a wide swath of the American economy.

"You would destroy the ability of Congress to legislate and agencies to administer, and you'd have no predictability for citizens to anticipate what they can and can't do. There's no way Congress can anticipate every situation or rule in every situation. That's why we set out broad rules," Democratic Rep. Jerrold Nadler of New York said in an interview.

More than 100 civil rights organizations that oppose Gorsuch's nomination include his views on the Chevron decision in their complaints about him. "He would relegate this vital precedent to the dustbin of history because it disfavors the corporate interests he championed as a lawyer and as a judge," the groups wrote in a letter to the Senate Judiciary Committee.

On the other side of the spectrum, some conservatives have hailed Gorsuch's opinion that called the Chevron doctrine into question. "It is one of the most prescient, comprehensive dissections of the doctrine that I've ever read," C. Boyden Gray, a former White House counsel, said earlier this month at a Heritage Foundation event on Gorsuch's nomination.

Republicans in Congress also share this disdain for handing so much power to regulatory agencies. The House of Representatives already has approved legislation on a near party-line vote that would override the Chevron decision and require courts to decide for themselves what statutes mean. Its prospects in the Senate are uncertain.

CHANGE AGENT?

Some experts in administrative law said Gorsuch's vote on the Supreme Court probably would not lead to a wholesale reversal, but could make the court pickier about when to defer to agencies.

Even now, the court does not always rely on the Chevron opinion. In its 2015 decision that upheld the Obama health overhaul's financial aid to middle- and low-income Americans to help them pay for health insurance, the justices pointedly refused to defer to the Internal Revenue Service's interpretation of provisions dealing with tax credits. But Chief Justice John Roberts said in his majority opinion that a ruling for the challengers would lead to a "calamitous result" that Congress could not have intended.

"Congress passed the Affordable Care Act to improve health insurance markets, not to destroy them," Roberts wrote.

The court's insistence on evaluating the health care law on its own -- without deferring to the IRS -- actually has worked to the benefit of supporters of the health care law, said Notre Dame law professor Jeffrey Pojanowski.

Had the court relied on the Chevron case, President Donald Trump would have had more freedom to undo parts of the law without Congress weighing in, he said.

A court that is less willing to defer to agencies could act as a brake against the Trump administration to the extent it relies on agency action instead of legislation to advance its agenda, Pojanowski said.

Still, any short-term gains for liberals during Trump's administration are sure to be outweighed over time, said Pamela Karlan, a Stanford University law professor and former Obama Justice Department official.

"Supreme Court justices are on the court for a good long time. Putting a justice on the Supreme Court who doesn't believe in any kind of deference to agency decisions means that even if five, 10, 15 or 40 years from now, the Democratic Party is in control of the White House and progressives are in control of administrative agencies, somebody who doesn't believe in deference may continue to override the will of the people on these things," Karlan said.