When you peel away the obvious outside differences, it turns out people and bananas have a lot in common.

Humans and banana trees are 60 percent genetically similar. We're even closer to chickens, sharing 75 percent of our DNA with the poultry. But chimpanzees are our closest cousins, matching more than 98 percent of our DNA.

These are just some of the fascinating facts unveiled in the National Museum of Natural History's newest exhibit: The Hall of Human Origins, which explores that age-old question: "What does it mean to be human?"

The National Museum of Natural History in Washington is marking its 100th anniversary by welcoming hundreds of visitors to the exhibit.

Early man

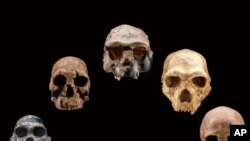

Visitors enter through a time-tunnel depicting faces of modern and early human, or "hominid" species. Nearby Curator Rick Potts stands at a display case that holds 76 hominid skull replicas, among the oldest known from six continents.

He says all of the species are gone. "Their ways of life are now no longer on earth. And we are the only ones left of a diverse family tree."

The more than 300 fossils and other artifacts in the exhibit illustrate a rich mosaic of physical and behavioral traits that evolved over time. Visitors learn about milestones along that journey: when humans stood upright, when brains became large, when social lives became complex, and when speech was initiated.

They peer into the eyes of life-like replicas of early humans, sit down at their ancestral hearth and walk in footprints molded from those left 3.6 million years ago in Tanzania.

"Those footprints are exactly at the spacing and the size of the footprints where three individuals walked across an African plain that long ago," Potts says.

Origin of mankind

Also on display are two historic human fossils. One is the 28,000 year-old skull of a Cro-Magnon - the first modern humans in Europe. The other is the skull of a Neanderthal, a species of hominid that co-existed with Cro-Magnon until they disappeared about 30,000 years ago. Both skulls are on loan from the Musee de l'Homme in Paris.

Alain Froment, who curates that museum's anthropology collection, says the fossils were discovered in France around the same time that Charles Darwin published his famous, "Origin of Species," in 1859. "It fueled the debate on the origin of mankind and the surprise was to find such a modern human in the fossil context with extinct animals."

Visitors are drawn to touch the ancestral replicas, to transform an image of their face into an early-human version and to interact with dioramas that convey the science of evolution, Potts says.

"What we've done in this hall is to allow people to explore the fossils from three points in time and touch the evidence. That activates a conversation with a scientist and ultimately activates, when you put all the clues together, an animated portrayal of a day in the life of early humans at three points in time."

Adapting to a changing world

This six-million-year-old story unfolds during an era of dramatic climate change, according to curator Rick Potts. He says the exhibit shows how, during great swings between warm and cool, and moist and dry, humans adapted to a changing world.

"Not only adapted to an African savannah or how Neanderthals became adapted to an ice age, but rather how our ability to make tools, our ability to have an expanded and complex brain, even our ability to use symbols and speak to one another, are not just adaptations to a past ancestral environment, but an adaptation to being flexible, to being adaptable."

That is a lesson 5th grade teacher Neisha Speights-Burno hopes to communicate to her students in Dumfries, Virginia. "For them to see the different skulls and tools," she says, "gives them more of a first-hand account that this stuff really did exist."

And it's a sense of connection that resonates with Charla Weiswurm from San Antonio, Texas. "I think that with all the conflict with everyone in the world that you come back saying, 'we all came from the same place originally, and why can't we just all get along because we are all exactly alike.' Why did we have to have such differences in everything?"

Curator Rick Potts hopes the exhibit helps answer that question by showing that our ancient relatives - once-living and breathing individuals - are worth getting to know.

And in knowing them, he adds, they can teach us what it means to be human.