A severe food emergency in Niger has prompted the U.N. World Food Program (WFP) to more than double its assistance to victims of this year’s drought in the eastern Sahel. As the West African country enters its lean season, WFP senior spokesperson in the United States, Jennifer Parmelee, says that $182 million is needed to relieve the food insecurity of more than half of the country’s population of 13.5 million.

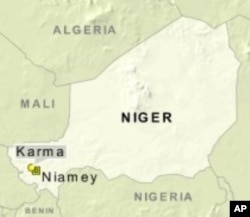

In February following a bitter constitutional crisis, a military junta removed longtime President Mamadou Tandja, who had tried to extend his term beyond ten years, from office. Parmelee says that with a new government in place in Niamey, providers are better prepared than they were five years ago, when an earlier drought destroyed harvests and dried up grazing lands, and the government did not acknowledge the crisis quickly enough.

“The last time around, it took the government quite a while to recognize the crisis, and that did feed in to the late response by the international community. But you have to look at Niger. In general, there are a multitude of structural issues. By almost any measure, it is the world’s poorest country. Years and years of deprivation have left them extremely vulnerable to any crisis that could come along. The last time, it was a plague of locusts, and this time it’s drought. Any crisis at all can tip over millions of people,” she cautioned.

The U.N., through its World Food Program and Emergency Relief Coordinator, is organizing development and humanitarian agencies to reinforce grain stocks and staff feeding centers to give particular attention to pregnant and nursing mothers, young children, and fragile patients already weakened by tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS. Spokesperson Parmelee says that community grain distributors are already in place and gearing up to provide greater supplies and subsidies during the peak of the crisis.

“There are these community cereal stores. They are aimed at women, who are traditionally looked at as the providers of food for the family, and they can indeed buy grain at subsidized prices. And we anticipate that getting to its peak at the peak of the lean season. Roughly, it runs from May to September, so that by mid-summer, we hope that these will be up and operating in full stream,” she noted.

Many school children are expected to receive meals during the crisis, and other vulnerable food recipients of imported food stocks include children under five in the worst-affected areas, who will receive supplementary feeding and infants under two, who will take part in a blanket feeding program, which Parmelee says is essential.

“This is designed to keep children in that very critical window of what we say zero to two years of age, which is for malnutrition a very critical stage of life. If you miss out on the main ingredients of nutrition in those years, you suffer the consequences in terms of both your physical stature and your mental development for the rest of your life. So it’s vital that we target this population of children,” she explained.

Parmelee says that because Niger is landlocked, local supplies are being obtained from neighboring Nigeria, an active trading partner with Niger. Added deliveries from another major provider, the United States, are expected to take as long as four months to arrive, but are said already to be in the pipeline.

Signs of drought over the eastern Sahel have lingered for about a year, destroying harvests and drying up grazing lands in a region that has long been subject to recurrent aridity. Niger’s last major food crisis in 2005 came on even more quickly and resulted in a higher loss of life than international aid agencies had anticipated. Despite a current shortfall of $98 million, coordinators say significant supplies are starting to roll in, and by doubling the target numbers of people they anticipate reaching, they hope to fend off the casualties of 2005 this time around.