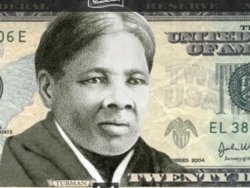

Harriet Tubman, a slave, renegade and human rights activist, is still a topic of controversy three years after the U.S. government announced it was putting her face on the $20 bill.

In May, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told a congressional hearing that plans to release the bill next year have been postponed until 2028. In the hearing before the House Financial Services Committee, Mnuchin said the $20 bill was being redesigned for “counterfeiting issues.”

“We were quite disappointed,” said Bill Jarmon of the Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center in Cambridge, Maryland, near where Tubman lived and worked.

Jarmon and his organization lobbied to have Tubman put on the bill, so the delay was a letdown. Yet, while the bill languishes, a new mural on the wall of the museum has unexpectedly raised interest in Tubman to an international level.

On June 24, Rich Delmar, acting Inspector General of the U.S. Treasury Department, announced his office will investigate the delay of the Tubman $20 bill. Delmar said his office will look into the delay as part of a previously scheduled audit, which is expected to take 10 months.

“If in the course of our audit work we discover indications of employee misconduct or other matters that warrant a referral to our Office of Investigations,” Delmar said, “we will do so expeditiously.”

President Barack Obama announced in 2016 the plans to put Tubman’s image on the $20 bill, making her the first African American and one of very few women ever to appear on U.S. paper currency. Presidential candidate Donald Trump denounced the move as “pure political correctness.” Once he took office as president, all mention of the Tubman $20 disappeared from the U.S. Treasury website.

Unexpected sensation

Meanwhile in Dorchester County, Maryland, people are flocking to the Tubman museum to learn more about her.

Many are inspired by an online image of the museum’s new mural by artist Michael Rosato, which has gone viral. Rosato, who is a professional muralist, lives just a few kilometers from Tubman’s birthplace.

Rosato’s mural features a larger-than-life Tubman reaching out to her viewer, extending a hand over an unfinished brick wall to draw the viewer out into the coastal wetlands beyond.

“I think it’s just part of the artwork that you just want to reach out and grab the hand,” said Katie Clendaniel, head of Downtown Cambridge, a local revitalization nonprofit.

So a little girl named Lovie did.

Her grandparents, who own a local boutique, posted the image. Soon, it was everywhere.

The effect on the museum was swift. Before the photograph was published May 15, Jarmon said, “We might have had maybe 15 or 20 people [per day].” Now, they average more than 60, he added.

The museum on Race Street is a decades-old, homegrown organization started by members of the community, some of whom have personal ties to Tubman’s extended family.

In 2017, the National Parks Service opened a Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Museum about 17 kilometers away, in the heart of the Maryland wetlands where Tubman lived and worked. Now, tour buses heading for the new museum outside town often stop at Race Street for photos with the mural. Many stay for the personal stories the volunteers and exhibits tell.

Tubman’s exploits

Tubman escaped in her early 20s. But using a secret network of travel and safe houses, she returned to eastern Maryland multiple times to guide family and friends out of slavery. She is believed to have rescued about 70 people on her own.

During the Civil War from 1860 to 1863, which pitted free states against slaveholding states, Tubman guided a raid in South Carolina that resulted in the rescue of about 700 additional slaves.

Yet, she labored in poverty for much of her life.

She struggled for years to claim military pay and a pension for her services during the Civil War. She sold pies and produce from her garden. An author published Tubman’s biography and gave her the proceeds.

Tubman died in 1913 in Auburn, New York, in a retirement home she had established for impoverished blacks. She was believed to be about 93, although she did not know her own birth year.

Jarmon, of the Tubman museum, said the scarcity of records about slaves and the Underground Railroad make Tubman’s story even more interesting.

“We’re always putting new pieces of the puzzle together,” he said.

Jarmon, who is black, says it wasn’t until a fundraiser for the museum a few years ago that he found out his own family name was a slave name. “No one ever shared that information with us,” he said.

Universal appeal

Amanda Fenstermaker, head of Dorchester County tourism, says these days interest in Tubman is driving foot traffic into the county’s visitor center. Even those coming in for some other reason, she says, want to learn about Tubman while they are in town.

Fenstermaker said she finds Tubman fascinating because she was an unlikely candidate for an anti-slavery hero.

“I mean, she couldn’t read, she couldn’t write. She was small, a woman, she had a head injury for most of her life. It just makes me think about how she was used by a higher power, and how much she ... is affecting people in this profound sort of way,” she adds.

Clendaniel, too, sees Tubman’s wide appeal.

“There’s definitely a global connection when it comes to civil rights and human rights,” she said. “I think for people who are struggling with liberty and identity and freedom, they’re going to want to know about someone like Harriet Tubman.”