The coronavirus pandemic lockdowns forced many bars and nightclubs across the United States to stand empty with their doors locked and chairs upside down on tables.

One hundred years ago, taverns in the U.S. were also locked down and desolate when the Volstead Act, better known as Prohibition, in 1920 became the law of the land, making it a crime to manufacture, sell or transport alcohol.

The drive to outlaw demon rum in the U.S. began in the 1850s. Churchwomen howled that whiskey was turning men into drunkards and barflies. Drink leads to violence and poverty and destroys families, they said.

Temperance movements, anti-saloon leagues and ladies storming into taverns to destroy bottles of whiskey grew from being an annoyance for the bartender into a legitimate political movement.

“Prohibition was largely driven by a feeling among certain portions of the population, although no evidence that it was ever nearly a majority, that alcohol was a bad thing and should be eradicated from American life,” said Daniel Okrent, The New York Times best-selling author of Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.

Okrent said brewers and distillers campaigned hard to defeat anti-alcohol politicians, popularly known as “drys,” even to the point of rigging elections. But, he said, the two industries were actually bitter enemies.

“The brewers say distillers are the ones who should be stopped distributing whiskey … beer, they said, was healthy. It was liquid bread. The distillers despised the brewers for making that separation. So, they really could not coordinate their activities together,” Okrent said.

Drinking did drop in the United States in the first years of prohibition, but flouting the law soon became a way of life in the 1920s.

Saloons known as speakeasies cropped up by the hundreds in large cities.

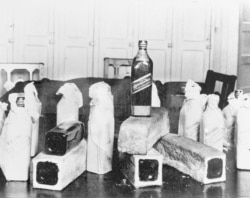

Bathtubs were used for other purposes than to scrub off grime and became huge mixing bowls for home brews – sometimes using gasoline and wood alcohol with fatal results.

Big overcoats and high boots suddenly became fashionable because they could easily conceal flasks, giving birth to the term “bootlegger.” People started walking with canes because the hollow ones could be filled with whiskey.

Anyone caught taking a drink immediately claimed the liquid was for “medicinal purposes.”

Many of the bootleggers who owned speakeasies and bought and sold whiskey were deeply involved in organized crime. Al Capone, Bugs Moran and Dutch Schultz became household names and legends, and extremely rich. The number of criminals involved in bootlegging outnumbered the federal agents who gamely tried to enforce the law.

Okrent said it wasn’t long before Prohibition became a huge joke.

“Anybody could get a drink any time of the day,” he said. “You could walk in at 10 in the morning get a drink. A 15-year-old could buy a drink. There was no regulatory environment. H.L. Mencken said to get a drink in Baltimore was very difficult unless you knew a judge or a cop.”

And foreign visitors to the United States regarded Prohibition as absurd.

“Winston Churchill — and you can imagine what he thought of Prohibition — came to the U.S. and toured the West in the mid- to late 1920s. He entered in Washington state, and the first person who gave him illegal liquor when he got into the U.S. was a Customs official. He traveled down the coast with his son, Randolph, and had no trouble finding alcohol,” Okrent said.

He said the Great Depression is what eventually killed Prohibition.

“The government was running on fumes, and people said, ‘One way we can get some revenue back is to bring back the tax on legal alcohol.’”

When President Herbert Hoover was introduced at baseball’s 1931 World Series, the thirsty fans welcomed him with loud boos and chants of “We want beer.”

Hoover was a dry. Franklin Roosevelt was a wet, and when he won the 1932 presidential election over Hoover, it was only a matter of time before Prohibition was finished.

The 21st Amendment overturned the 18th, and drinking became legal again in the U.S. in December 1933.

Today’s regulatory regime on alcohol sales and consumption is a hangover from Prohibition, including taxes, age limits, mandatory closing hours for bars and restrictions against opening a tavern near a church or school.

Okrent said the irony is that it is harder to get a drink these days, when it is legal, than it was in the 1920s when it was not.