For Asian Americans already feeling vulnerable after a year of surging race-based violence during the coronavirus pandemic, Tuesday’s deadly attacks at three Atlanta-area massage parlors took traumatizing fear to a new level.

“It was shocking to see, but also terrifying,” Kimberly Ha, a New Orleans-based photographer of Vietnamese descent told VOA. The city and its suburbs are home to a vibrant community of more than 15,000 Vietnamese Americans.

Ha said when she first learned of the attacks, which killed eight people including six Asian Americans, she thought of her mother, who works in a salon not unlike those targeted in Atlanta.

“Sometimes she works by herself, or she’s opening and closing the store alone,” she said. “That’s the first thing that came to mind when I saw the shootings. If something happened, I wouldn’t be there to protect her.”

While 21-year-old shooting suspect Robert Aaron Long’s motives remain under investigation, Tuesday’s killings came amid an eye-popping rise in attacks against Asian Americans. While hate crimes overall fell by 7% in 2020 compared with 2019, those targeting Asian Americans jumped 149% in 16 major American cities last year, according to a study released this month by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism.

Khai Nguyen works for two nonprofit organizations that support — among others — New Orleans’ Vietnamese American community. He said it would be impossible to look at Tuesday’s shootings and not feel less safe. He added, however, it’s something he’s had to deal with most of his life.

“I’m a pretty careful person, and I’ve learned it’s important for me to be vigilant,” he said, “because Asian people have always been seen as an easy target to bully.”

Refugees build a new home in New Orleans

“With very few exceptions, I’ve always felt welcome in New Orleans,” said Ly Vo Morvant. “The city’s been a melting pot of so many different cultures throughout its history.”

Today’s Vietnamese American community in New Orleans is the product of refugee resettling that began in 1975. That was the year U.S.-backed South Vietnam fell to communist North Vietnam, triggering a massive operation to relocate nearly 140,000 refugees across the United States.

More than 2,000 of them came to New Orleans, attracted to a region that felt at least somewhat familiar — an often-sultry climate, a thriving fishing industry, and a substantial number of Catholics.

But in those early days, the U.S. public was not welcoming of the new immigrants. A May 1975 Harris poll showed 37% of Americans were in favor of accepting Vietnamese refugees, a lower percentage than favors the United States taking in Syrian refugees today.

While Nguyen said he feels perfectly at home in New Orleans, he’s heard stories of how difficult it was for the first Vietnamese arriving here.

“On the one hand, they were placed out in far-off public housing buildings and you had these two cultures — African Americans and the Vietnamese — who didn’t know anything about each other and didn’t speak the same language,” Nguyen explained. “And on the other hand, you had these new arrivals from Vietnam competing with local Louisiana fishermen. I’ve heard it caused a pretty violent reaction.”

In more recent decades, however, as New Orleanians came to know their newer neighbors, a new generation of Vietnamese Americans has emerged that proudly calls New Orleans home.

“I think a lot of the progress was actually related to food,” Nguyen said. “As Vietnamese restaurants started to open around the city in the last couple of decades, I think New Orleans kind of took in parts of Vietnamese culture. That’s also made Vietnamese people here more comfortable traveling outside our isolated enclaves.”

Microaggressions

For some, the Atlanta shootings have tapped into a minority community’s disappointment and simmering resentment over being seen as – and treated as – less than fully American.

Even though New Orleans prides itself as a welcoming, diverse city, Nguyen and others said there is no escaping a sense that non-Asian residents see them differently.

“It’s not that I feel discriminated against,” he said, “it’s that I feel like people see me as ‘the other’ — like I don’t quite belong here.”

Nguyen said sometimes, when he’s talking to someone he hasn’t met before, they’re surprised to hear how well he speaks English.

“They’d compliment my English, but I’ve lived here nearly my whole life,” he said. “They don’t mean to be rude, but they’re basically saying that if you look like me, you probably aren’t American.”

Morvant said sometimes these microaggressions can become more blatant and derogatory.

“I’ve had people come up to me just to say ‘Ching-chong [racist taunt],’” she said, “and I’ve had someone approach me and say, ‘You look like someone who does my nails!’ I’ve even had a white man come up and start speaking Thai to me. I’m American just like him.”

When former President Donald Trump used phrases like the “Chinese virus” or “kung flu” to describe the coronavirus, Ha said, he emboldened untold numbers of people to falsely blame Asian Americans for the pandemic.

“I’ve walked into a room and seen people immediately put their mask on because they think an Asian woman must be more likely to have the virus,” she said, “and I’ve even had taxi drivers who have felt comfortable enough to ask, ‘Are you from where the virus was made?’”

Leading to violence

The problem with these nonviolent examples, said Ha, Nguyen and Morvant, is that it can lead to something much worse.

“When you see us as ‘other’ than you, you’re dehumanizing us,” Nguyen said, “and when you dehumanize us, it’s much easier to be violent.”

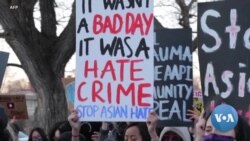

There’s a heated debate taking place about whether Tuesday’s shootings were a hate crime. Those who believe it wasn’t a hate crime point to the suspect’s statement that it was a shooting meant to eliminate sexual temptations rather than to kill a specific group of people.

But Morvant and many others insist that just because the shooting suspect said it was a crime related to sexual addiction doesn’t mean it wasn’t also a crime targeting Asian American women.

“Look at the way Asian women are treated in the media,” she said, “submissive and hypersexual. Have you seen the play Madame Butterfly or heard people use the derogatory phrase ‘yellow fever’? White men like this guy in Atlanta sexualize us and dehumanize us.”

Ha agreed.

The suspect “stated he killed those people because of his sexual addiction and that he’s not racist,” she said, “but he chose three shops where Asian American women work. That’s not a coincidence.”

Nguyen believes that for violence like this to be avoided, it’s important for America to reframe the way it looks at its minority groups.

“People need to stop seeing us as monoliths,” he said. “Black people aren’t one big group, Latinos aren’t one big group, and Asians aren’t one big group. It doesn’t make sense to blame everyone who looks Asian for a pandemic, just like it doesn’t make sense to see Asian women in a certain, singular way.

“One thing every American has in common is that we’re not a monolith. I’m an individual; but I share a lot of the same goals you do, and this country belongs to me exactly as much as anyone else.”