In January, a woman calling herself Caroline — her name is changed for her safety — told WOI-DT in Iowa that she was married to a QAnon believer and lived in fear. “QAnon has destroyed my life,” she said. “I live with someone who hates me.”

In May, a Reddit user known as pencilwithouteraser posted in the forum ReQovery, that he was seeking help coping with his parents’ immersion in QAnon conspiracy theories and their objection to the coronavirus vaccines.

“I still don’t know what’s true or not,” the user said. “I’ve realized that once you start to go down those rabbit holes, it’s very hard to come back to the surface. If you believe the media, CDC, and WHO are lying about the vaccine in the name of conspiracy and power and control, how can your mind be changed?”

A British woman named Tasha wrote her testimony on the web page for the documentary film The Brainwashing of My Dad. Her QAnon father, she wrote, “has cut off his brothers and sister. … He shares the most vile things on Facebook. He’s turning into a vile, hate-filled man.” She concludes: “I have such a hatred for the architects of QAnon, because their lies have broken my family.”

Surveys show that these grieving family members are far from alone. The number of people invested in QAnon conspiracy theories is striking, and their devotion to the cause can make life difficult for the people who love them.

The Public Religion Research Institute released a survey in May that showed just how many people believed in some tenets of QAnon.

Fifteen percent of the more than 5,000 people surveyed nationwide said they believed the following sentence: “The government, media, and financial worlds in the United States are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global sex-trafficking operation.”

That’s the core QAnon belief. But QAnon has expanded to encompass various other beliefs. For example, some believers maintain that John F. Kennedy Jr. is still alive, that German Chancellor Angela Merkel is related to Adolf Hitler, and that President Donald Trump will be proven the rightful winner of the 2020 election and be reinstated to invoke a “coming storm” of retribution.

Belief in the coming storm is greater than the core QAnon belief in pedophiles and Satan worship. PRRI says 20% of Americans agreed with the statement “There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders.”

Observers are most concerned with the fact that 15% of respondents agreed that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

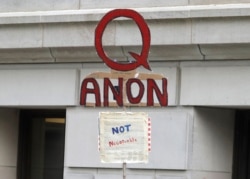

The danger of QAnon became clear on Jan. 6, when hundreds of Trump supporters — many wearing or displaying QAnon paraphernalia — broke into the U.S. Capitol Building in an attempt to disrupt certification of Joe Biden’s win in the November presidential election.

The FBI has since made public a declassified report warning that some QAnon adherents are “domestic violent extremists” who may be motivated to stage terrorist attacks on perceived enemies.

Mike Rothschild, journalist and author of a new book about the QAnon movement, The Storm Is Upon Us, wrote that the us-against-them mindset of QAnon followers is what makes the movement so damaging.

“For many Q believers,” he said, “that nebulous feeling that ‘they’re all out to get me’ becomes … ‘I’m gonna get them first.’”

Cult expert and mental health professional Steven Hassan, author of the book The Cult of Trump, said the QAnon community shares some traits with cults. Members feel a rush of information and indoctrination at the start, followed by messages that nothing outside the group is trustworthy and that others need to be brought into the fold.

Experts say people are attracted to conspiracy theories when they aren’t comfortable with uncertainty. A 2017 study in the European Journal of Social Psychology found that what attracts people to conspiracy theories is a need for “cognitive closure” — a reason, or something to blame.

But life as a conspiracy theorist is exhausting, Rothschild said, because it infects every part of your thinking.

“At its worst, QAnon absolutely rewires the way you look at the world,” he said. “It gives you a sort of cast of characters who are the good guys and who are the bad guys. And you look at everything through the lens of that war that’s being fought.”

Rothschild has talked to people who have cut off relationships with QAnon believers. They say the person wouldn’t talk about anything else or was constantly sending messages and videos meant to draw them into QAnon.

“It takes too much work to be around a person like that,” he said.

Experts say it can be challenging to help a loved one who has gone down the QAnon rabbit hole. Both Hassan and Rothschild say people tend to lose their faith in the group when they start to see holes in the information they’ve been accepting. Meanwhile, they say, building trust is the key to helping a QAnon believer see the light.

“The easiest way is to simply present yourself as a safe person to talk to,” Rothschild said. “You’re not belittling them. You don’t mock their beliefs.”

Hassan, who left the Unification Church cult in the 1970s after an intervention from his father, recommends starting a dialogue with the QAnon member, not trying to debunk QAnon beliefs.

“I propose that we reciprocate,” Hassan said, demonstrating the way such a conversation might go. “You share something that was very influential to you, and let’s go back in time. What were some of the most important things that convinced you to take it seriously? If it’s a video … let’s watch it together and we’ll discuss it.”

After that, Hassan said, the interventionist might share a video with a different perspective and suggest they discuss that.

“The idea is always to ask a respectful question aimed at empowering them to think for themselves,” Hassan said.

Hassan recommends some protective habits to help anyone guard against misinformation.

“I advocate creating ‘trust pods’ in your life,” he said, that include people with differing perspectives. “If there’s something that any one of you gets really interested in, before you spend money or spend a lot of time, say, ‘Hey I just found this. … Anybody know anything about it?’”

“That’s the solution to blind faith,” he said. “It’s perspective, isn’t it?”

But the pull of QAnon is strong, and not everyone leaves. In a world where little seems to make sense, QAnon’s mythology seems to offer hope.

Former QAnon believer Lenka Perron explained to WDIV-TV in Detroit, Michigan, in January: “When people don’t feel secure, when they don’t feel safe, when they don’t feel like they can put a roof over their heads … they turn to something where you feel powerful, like you can make it happen. You feel like you’re making a difference.”