Tourists walk through an old Victorian-style row house in Washington's most historic African American neighborhood. As they move through rooms and up narrow stairwells, many are unaware the man who lived and worked here established the first black history observance.

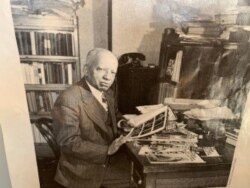

The home of Carter G. Woodson stands as a lasting tribute to the black historian, author and teacher who devoted his life to showcasing the treasures of African American history.

“Woodson was a man with purpose. He set out to help African Americans uncover a lot of the truth about their history that seemingly was kept from them,” said National Park Service Ranger John Fowler. The group of ethnically diverse visitors listens as Fowler points to the room where Woodson established “Negro History Week” in 1926. Now, the U.S. tradition is observed as Black History Month in February.

The son of former slaves, Carter Woodson was born in Virginia in 1875. Despite racism during the post-civil war reconstruction era, Woodson reached the heights of American educational attainment, earning a doctorate degree from Harvard University in 1912.

In 1922, he purchased the red brick home for $8,000 in the Shaw neighborhood, known as the “Heart of Black Washington.” The historic site is run by the National Park Service.

“Dr. Woodson’s spirit and all those who worked in here with him still reside in this home,” said Barbara Dunn, vice president of membership for the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). Woodson founded the organization in 1915 with a sole mission: to document black life, history and culture.

“From 1922, when Dr. Woodson purchased this home, until 1950, when he died in this home, the major work that he did here laid the foundation for recording the black history we study today,” Dunn said. "Woodson was passionate about promoting, researching, interpreting and disseminating information about black history.”

Historians note Woodson's groundbreaking work compiling and disseminating census data on America's black population. In addition, he collected and preserved historically valuable manuscripts from African American writers like Booker T. Washington.

These works, shunned at the time by the Library of Congress, were later published by Woodson in the "Journal of Negro History." It was the first academic publication written for and by people of African descent.

Other publications were created for the schoolroom so that teachers could ensure children learned about black history.

A U.S. tradition of celebrating black history

In 1926, Carter Woodson sought to increase public awareness of black history, establishing the annual February observance of “Negro History Week,” which later became “Black History Month” in 1976.

The tradition was born out of the belief that if African Americans were to take their rightful place in American society, people of all races should learn about black contributions to the nation.

“He connected us to the rest of the world because our beginnings started in Africa. And even today all over the world, black history month is recognized and people are beginning to understand it was never meant to just be a week or a month but is to be studied for the entire year,” Dunn said.

Historians maintain Woodson chose February for the black history observance because Feb. 12 was President Abraham Lincoln's birthday and Feb. 14 was the accepted birthday of Frederick Douglass. Both men fought to end slavery in the United States and are viewed as heroes in the African American community and among many Americans of all races.

“I wonder even if there would be African American history as it is without Woodson really fighting for that and committing his life to it,” said tourist Julia Goodman-Gafney, a high school history teacher from Prince George’s County, Maryland. “I try to share the rich history with my students and tell them we use Black History Month to celebrate what we learned, not just to learn. This is supposed to be the celebration of the contributions people of African descent made to this country.”

Said Fowler: “Dr. Woodson felt that if he could somehow influence the masses by revealing this history, this historical truth that the lives of people of African descent were more than just [victims of] slavery. He believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among blacks and whites could reduce racism.”

Dr. Woodson “knew people would not publish what he was writing. So he started his own publishing company right in this home,” noted Dunn.

During Woodson’s life, Washington was a segregated city with blacks only allowed to live in certain neighborhoods. Woodson’s home became an institution in the area where blacks could gather and learn. “This home is where Dr. Woodson would train and mentor a lot of the leading scholars, activists and historians. He wanted this home to be a cultural center and he achieved that,” said Fowler.

As visitors filed out of the home, tourist Stan Thompson paused, then said, “Mr. Woodson would be proud that people of all races can live in this neighborhood today and tourists from all over can come here to learn about the history Carter Woodson fought so hard to preserve and publicize."