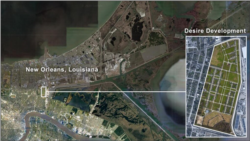

Maintaining a balanced diet has never been easy in Desire, a predominantly African American neighborhood in New Orleans, Louisiana, but it has become nearly impossible during the pandemic.

“We’ve always had inequality problems to deal with, but coronavirus has made it worse,” high school junior Chrishana Simon said. “The stakes are so much higher now.”

Despite being a hub of gastronomic pursuits much celebrated for its Cajun cuisine, Louisiana ranks near the bottom of U.S. states in providing its residents access to healthy and affordable food, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In New Orleans, the nonprofit group Feeding America estimated 85,000 residents - 22% of the population - were unable to find or afford fresh food in their communities. Those residents were disproportionately likely to be black.

“My family and I are afraid to go to the grocery store,” Simon explained. She said a trip for fresh groceries would involve a bus trip across town and entering a busy supermarket, both of which could expose them to the virus. Fearing especially for the health of her grandfather, they have limited shopping to quick runs to a neighborhood convenience store, where Simon is more likely to find chips and soda than fruits and vegetables.

“For the first month of the pandemic we lived off of canned foods and rice and beans,” she added. “We had no better choice.”

The consequences of nutritional deficiencies are impossible to miss - especially during the pandemic, according to Connor DeLoach of Top Box Foods, a nonprofit that provides fresh produce and other goods at heavily discounted prices in New Orleans and elsewhere.

“If you aren’t putting healthy food in your body, the long-term effects can be seriously detrimental,” he said. “New Orleanians have higher rates of high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes than the national average and these are all conditions that make individuals more susceptible to coronavirus’ most intense symptoms.”

In Louisiana, where black people make up about one-third of the population, Gov. John Bel Edwards said last month they accounted for more than 70% of the state’s coronavirus deaths. The majority of these fatalities were recorded in New Orleans.

Food Deserts

The USDA defines “food deserts” as places where residents must travel more than a mile (1.6 km) to reach a supermarket. It’s estimated that approximately 23.5 million Americans live in such neighborhoods.

Simon said the nearest grocery store to her home is a Walmart about three kilometers away. But just because there isn’t a grocery store nearby doesn’t mean her neighborhood is void of food.

“We have a Rally’s, a McDonald’s, a [Raising] Cane’s,” Simon said, listing her neighborhood’s unhealthy fast food options, “a Taco Bell, a Wendy’s -- pretty much every chain you can imagine - and, of course, plenty of corner stores.”

She said she often craves a fresh salad rather than sugary or greasy foods. “But you can’t really get that around here.”

This is nothing new, according to Shawn “Pepper” Roussel, an advocate for equitable food access in New Orleans, noting that food deserts have existed for decades.

“It started with white flight [abandoning urban areas] in the 1950s and ‘60s,” she explained, “which left poor and African American families in partially-abandoned inner cities alone.” As population size and purchasing power declined, many stores closed, including supermarkets.

Roussel disputes any suggestion that poor people don’t want to eat healthy food.

“That couldn’t be further from the truth,” she says. “The reality is, after white flight, finding healthy food in inner cities was pretty much impossible.”

Making matters worse

For Simon and her family, taking public transit to and from a grocery store was an arduous trip before the pandemic. Now, that option is even grimmer.

“Riding a public bus feels like a big risk right now,” she said, “and they’re running less hours and less often because of the virus.”

Walking 40 minutes to Walmart is even less appealing. “And have you tried walking two miles with grocery bags? You can’t carry all the fresh food your family needs.”

To make matters worse, most food delivery services - a preferred option for many Americans sheltering at home - don’t accept food stamps, effectively shutting out the poor and vulnerable who rely on the government assistance program for grocery purchases.

If Simon’s family does risk entering a supermarket, they’d find fresh food even further out of reach. April marked the largest one-month jump in grocery prices in the United States since February, 1974.

Change

While food is more expensive, many in New Orleans have seen their incomes plummet. More than 130,000 residents filed unemployment claims between March 21 and April 11 - nearly 25% of the city’s pre-COVID 19 jobs.

As in many cities, New Orleans’ minorities have been especially hard hit, losing jobs tied to the city’s large tourism industry that has been decimated by the pandemic. African Americans account for more than half of cooks and janitors in the city, and more than two-thirds of housekeepers.

At a time of growing need, nonprofits like DeLoach’s Top Box Foods are swinging into action, delivering boxes of fresh produce, fruit and meat to customers’ doors - including to those who rely on food stamps. The organization is also working with corner stores to sell more fresh produce and other healthy food.

Chrishana Simon, meanwhile, can envision a better future in which she walks through her neighborhood and no longer sees a never-ending parade of fast food restaurants.

“When I’m in other neighborhoods, sometimes I see they have people growing food in gardens. There are stores with fresh vegetables,” she says. “Why can’t that be my neighborhood? My family deserves the chance to be healthy, too, don’t we?”