Across Indian Country, summer pow wows provide opportunities for tribe members to reconnect and celebrate cultures that have survived despite historic efforts by government and religious groups to erase them. But the 47th Annual Oneida Nation Pow Wow, held last week in Oneida, Wisconsin, was also an occasion for solemnity, as the tribe welcomed home the remains of three teenage girls who died far from home more than a century ago.

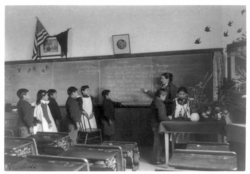

Beginning in the 1870s, the U.S. government placed thousands of Native American and Alaska Native children in boarding schools, a practice that continued until the 1970s. Given English names and forced to wear western-style clothing, students were banned from speaking their languages or engaging in traditional religious practices, part of a widespread effort to “Christianize” and “civilize” the Indian.

Education focused on teaching youth vocational, not academic, skills — farming, cooking, or laundering — and many students were farmed out to families to work as maids or learn trades such as blacksmithing.

More than 10,000 Native children from tribes across the country were sent to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, regarded at the time as the “crown jewel” of the Indian boarding school system. But after arriving there, nearly 200 students died, most of them victims of infectious diseases that could have been prevented by better nutrition and sanitation.

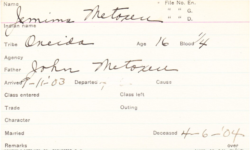

Sixteen-year-old Oneida tribe member Jemima Metoxen was one of them. While scant, her school records indicate she was supposed to spend five years studying at Carlisle, but in April 1904, just seven months after she arrived, Metoxen died of spinal meningitis and was buried in the school cemetery.

Metoxen wasn’t the first member of her tribe to die at Carlisle. A dozen years earlier in 1893, pneumonia claimed the life of Ophelia Powless, and in 1895, Sophie Coulon, who had been hired out to four families in three states, also died of pneumonia.

A further look at Carlisle school records, digitized and made available by nearby Dickenson College, shows that in 1896, 21-year-old Jemima John died of causes unknown after only two years into her second admission to Carlisle. In 1897, another Oneida teenager, Melissa Metoxen, died at age 16.

Bringing them home

In 2016, under pressure from several Native tribes and Nations, the U.S. Army agreed to begin disinterring and returning home the remains of those buried in the Carlisle cemetery.

The Oneida Nation delegation, which included Oneida Councilman Kirby Metoxen, traveled to Carlisle in mid-June to claim the girls' remains. He spoke about the experience to Green Bay, Wi. Fox News affiliate, WLUK-TV.

“As I’m sitting there and all the emotions and all the stories I heard and the thoughts of these children not having any family when they passed and I just had compassion for them,” he said.

The three girls were honored during the powwow’s opening ceremonies on Friday, June 28. On Sunday June 30, they were finally laid to rest: Metoxen and Caulon at the Oneida Sacred Burial Grounds, and Powless at Holy Apostles Cemetery, the site of the Episcopal Church’s oldest Indian mission.

“It’s kind of a relief on your body and your mind and soul,” Henry “Hank” Huff said. “Plus there’s a warmness in your heart that they’re back here by their family.”

Editor's note: Headline photo shows pallbearers (L to R) Oneida Nation Councilman Kirby Metoxen, Ryan Funeral Home Managing Director James Wolfe, Councilman Daniel Guzman-King, Wayne Cornelius, and Mason Laster carrying the remains of Ophelia Powless into Holy Apostles Church, Oneida Nation, Wisconsin, June 30, 2019. Photo courtesy of Dawn Walschinski/ Kalihwisaks.