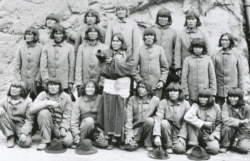

In late October 1912, 15-year-old Agnes White, left her home on the St. Regis Mohawk reservation in northern New York to begin five years of vocational training at the Carlisle Industrial Indian School in Pennsylvania. She would never see home again.

Records show White spent only a year in the classroom. The following May, she was farmed out on the first of four work details as a servant in white households. That fall, a Philadelphia surgeon operated on her eyelid to correct a malformation caused by trachoma, a highly contagious eye infection that was epidemic throughout the boarding school system and a major public health concern.

A year later, on a third “outing” as a domestic, her employer reported that White was having trouble breathing, owing to the “heavy air.” In September, just two weeks into her fourth outing, Agnes died of appendicitis.

White is one of a few students whose remains were shipped home to family for burial. At least 200 others were buried in marked or unmarked graves on Carlisle grounds.

The recent discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous students in a mass grave at the Kamloops Indian Residential School in Canada has refocused attention on the fate of students like White and thousands of other Native American children who were seized from families and sent to remote boarding schools, never to be heard from again.

Some ran away and created new lives. But the majority died of infectious diseases that flourished in crowded dormitories at Carlisle and hundreds of other boarding schools that operated between 1879 and the 1960s.

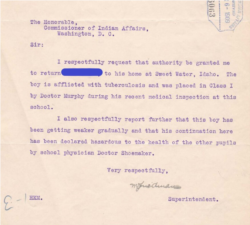

Making matters worse, schools often sent the sickest children home to infect families and communities.

“As a result of that, how can you even begin to figure out numbers?” said Preston S. McBride (Comanche descent), a post-doctoral fellow in Native American Studies at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. “It's obvious that you can't, and that ultimately, any accounting of the true demographic impact of boarding schools is going to be inadequate.”

Odors, flies

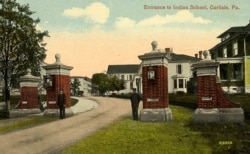

U.S. Army General Richard H. Pratt established the first federal off-reservation boarding school aiming to “transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization” and inspire Native loyalty to the U.S. flag.

It wasn’t long, however, before word began to spread that students were dying at school. Families who resisted sending their children faced punishment: In 1894, for example, 19 Hopi fathers were imprisoned for a year on Alcatraz Island.

Historian and author David H. Dejong writes that in 1903, Indian Affairs Commissioner William Jones ordered the first survey of Indian health, and when finding that conditions at the schools were worse than Jones imagined, he directed schools to conduct health screenings on prospective new students and to clean all dormitories.

But mortality rates continued to climb, and in 1922, Indian Affairs Commissioner Charles Burke called on the Red Cross for help. Florence Patterson, a nurse who had served in World War I, surveyed several Southwest and California reservations and boarding schools. Her descriptions of boarding school conditions were shocking.

“The toilets … consisted of a long trough, which was supposed to be flushed automatically at regular intervals,” she wrote of the Fort Yuma boarding school. “They were … found to contain no water and not to have been flushed for some time. The odors were obnoxious, and the flies plentiful.”

She described dark and gloomy dormitories with “little ventilation and practically no sunshine,” insufficient diets and exhausting hard labor, concluding that these enabled, rather than prevented, the spread of tuberculosis.

By 1928, matters had not improved, according to the Meriam Report, which described the impact of federal policy on Indians.

“The prevalence of tuberculosis in boarding schools is alarming,” it read, blaming overcrowding, poor diets and grueling labor.

McBride places much of the blame on U.S. lawmakers.

"Ultimately, a good portion of disease and death in these institutions was the result of underfunding by Congress for decades and decades," McBride said. “The federal government blamed tuberculosis on Indigenous bodies, rather than the conditions in the schools that contributed to the spread of disease.”

Deliver the truth

Research has shown that many of the health and social problems facing tribal communities today are the result of historic trauma and unresolved grief.

Christine Diindissi McCleave, a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation and CEO of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS), has made it her mission to find out who these children were and what happened to them so communities can heal. [

It is a daunting task. Today, records are scattered in government and church repositories across the country.

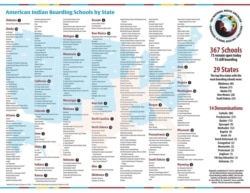

In 2016, the NABS joined a coalition of advocacy groups to submit a Freedom of Information Act request to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), asking for names and locations of all boarding schools, enrollment lists, student deaths and burial locations.

As VOA reported in 2017, the BIA asked for extra time but failed to follow through, and closed the case without notifying the NABS. McCleave said the BIA reopened the request, but she has heard nothing since.

“We are now focused on finding the records ourselves,” she said. “So far, we have identified 367 boarding schools and located records for 142 of them. That’s only 38% of what’s out there.”

VOA’s request for comment from BIA was unanswered at the time of publication.

In 2008, Canada established a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to document the history of its residential school system and acknowledge its impact on Indigenous communities. McCleave hopes the U.S. will do the same.

“This country has a lot of things to face that it's not facing,” she said.

In late September 2020, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren and then-Congresswoman Deb Haaland, a citizen of the Laguna Pueblo, introduced the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy in the United States Act, which calls for a national commission to investigate and document the Indian Boarding School Policy and acknowledge the trauma inflicted on generations of Native families.

In an editorial June 11 in The Washington Post, Haaland, now Interior secretary, cited her family’s experience in boarding schools, asking that survivors and families be given a chance to tell their stories.

“Though it is uncomfortable to learn that the country you love is capable of committing such acts, the first step to justice is acknowledging these painful truths and gaining a full understanding of their impacts so that we can unravel the threads of trauma and injustice that linger,” Haaland wrote.