Native Americans are expressing outrage over President Donald Trump’s planned fireworks display Friday at Mount Rushmore in South Dakota, a monument on land they say was stolen from them more than a century ago.

They also question the timing of the event, scheduled during a period in which Americans struggle to come to terms with racism and police violence, and underfunded tribes battle the spread of COVID-19.

“He hates Indians,” Terry FastHorse, a Sicangu Lakota citizen and Lummi descendant, said of Trump. “There's no other reason to be there.”

Fellow Sicangu Lakota citizen Phil Two Eagle agreed. He is executive director of the Sicangu Lakota Treaty Council, which works to assert the treaty rights of the Oceti Sakowin Oyate (Seven Council Fires), the proper name for the historic confederation of tribes with claims to the Black Hills.

“To me, Mount Rushmore is a symbol of ethnic cleansing, forced assimilation and the theft of our territory,” Two Eagle said. “Trump is just reminding us of the continuing genocide of our people.”

Backdrop

In 1868, the U.S. government signed a peace treaty with Dakota, Lakota and Arapaho leaders, designating as the “Great Sioux Nation” territory that stretched across parts of North Dakota, South Dakota and four other states and guaranteeing the tribes “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation.”

But that was before miners led by General George A. Custer found gold in the Black Hills, setting off a flood of prospectors who demanded protection by the government.

Under pressure from the miners, the U.S. Interior Department sent a commission to negotiate purchasing the Black Hills but refused the tribes’ asking price. Congress then passed an act in 1877 reclaiming the Black Hills and consigned the tribes, at threat of cutting off all their rations and supplies, to five small reservations in South Dakota.

The dispute continues. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1980 that the government had illegally seized the Black Hills and ordered tribes be compensated nearly $106 million. The tribes refused the money, wanting the land returned instead. Today, those funds, worth more than $1 billion with interest, sit untouched in Treasury Department coffers.

But South Dakota tribes say it isn’t about the money. They have long cited sacred links to the Black Hills, claims that are supported by ethnographic and historic documents, including rock art with religious themes that dates back millennia.

“We consider the Black Hills as an altar,” said Two Eagle. “We have sacred sites there that tie us to our Lakota astronomy. For thousands of years, we’ve gone there to pray.”

Memorial to racism?

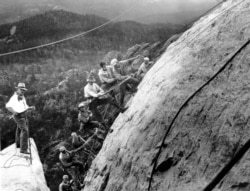

In 1924, the South Dakota state historian commissioned Gutzon Borglum to design and carve a “heroic sculpture of unusual character” in the Black Hills. Three years later, hundreds of workers began blasting the southeastern face of Mount Rushmore, and spent 14 years carving 60-foot portraits of U.S. Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt – leaders that many Native Americans view as racist architects of settler expansion and tribal subjugation.

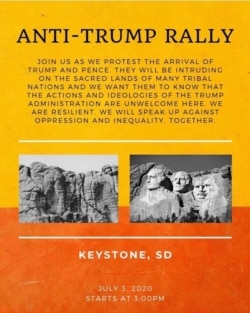

On Friday, they plan on voicing their opposition to both Trump’s visit and the monument itself.

“There’s a rally scheduled in Keystone, which is about a mile away,” said journalist and activist Darren Thompson (Lac du Flambeau and Tohono O’odham), who will travel from Wisconsin to attend. “To my knowledge, there won’t be a protest at the park because it wouldn’t be allowed.”

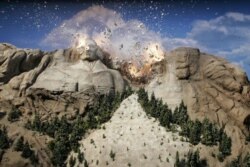

An image of Mount Rushmore exploding into pebbles and dust has circulated on Facebook, bolstering claims by some conservatives that protesters are planning to topple Mount Rushmore as they have Confederate statues and monuments.

Not possible, said Thompson, who knows the park.

“The security is so tight there, the only way it could be done is if it were an inside job.”

Trump has signed an executive order promising to prosecute, “to the fullest extent possible under federal law” anyone who “destroys, damages, vandalizes, or desecrates a monument, memorial, or statue within the United States” and to withhold funding from state and local police who fail to protect monuments.

My Executive Order to protect Monuments, Statues etc., IS IN FULL FORCE AND EFFECT. In excess of a 10 year prison term. Please do not put yourself in jeopardy. Many people now under arrest!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 1, 2020

Oglala Lakota President Julian Bear Runner told the Argus Leader last week that he believes the carvings should be removed.

“Removed but not blown up,” he said, “because that would only cause more damage to the land.”

Harold Frazier, chairman of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, this week called the monument a “brand on our flesh,” adding that he would be willing to remove it by himself, free of charge.”

Most Native Americans who spoke with VOA prefer to see the monument remain and used as a teaching tool.

“Why can’t we build a museum down at the bottom to honor our people and acknowledge their existence?” asked FastHorse.

This is exactly why I introduced the Mount Rushmore Protection Act. Rather than telling the story of our history, some are set on erasing it. pic.twitter.com/6Nedkj9NLW

— Rep. Dusty Johnson (@RepDustyJohnson) June 30, 2020

Republican congressman Dusty Johnson of South Dakota last week introduced a law that would ban using federal funds to alter, destroy or remove the faces on the Mount Rushmore Memorial.

“These presidents championed the cause of freedom,” he said in a June 25 statement. “Those seeking to remove these iconic faces are undermining the contributions these leaders made in pursuit of a more perfect union.”

![Letter written by the South Dakota state historian to sculptor Gutzon Borglum [his name is misspelled in the letter] requesting he design and build a sculpture at Mt. Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota. (Image: Facebook)](https://gdb.voanews.com/1ebab606-4fa7-4b3b-b6dc-ea594a88ead6_w250_r0.jpg)