Abdul Smith, a 42-year-old African American resident of Santa Monica, California, made six attempts to vote in his state’s Democratic primary on March 3. Long lines at polling stations defeated him each time.

“It was the first vote I’d missed since my 18th birthday,” Smith told VOA. “Every time I went to a new polling location, the line was even longer. I couldn’t find anywhere with less than a two-hour wait.”

California now allows voters to cast ballots at any polling place in the county where they live. Smith works from home, and repeatedly attempted to vote between morning meetings. He tried again in the afternoon but had to leave to pick up his daughters from school.

“By then, the lines were stretching down a stairwell, out a building and down one-and-a-half city blocks,” he said, adding that he intended to vote for Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

Others have persevered for as many as seven hours. Some of the longest lines in America’s primary season to date were reported in Houston, Texas, where Alex Palmer waited for nearly five hours earlier this month to cast a ballot for Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders.

“These elections are too important to miss,” said Palmer, a recent college graduate. “I wanted my voice to be counted, no matter how long it took.”

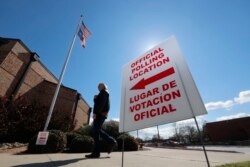

Palmer’s polling place is located at Texas Southern University, a historically black institution of higher learning in a city with large African American and Hispanic populations.

Unusually long lines have not been limited to California and Texas. Twenty-four states held nominating contests ahead of Tuesday’s primaries in Florida, Ohio, Illinois and Arizona. Polling stations from Dallas, Texas, to East Lansing, Michigan, to San Francisco, California, all reported frustrating delays. In Fargo, North Dakota, hundreds of voters stood in minus-10-degree Celsius weather for more than two hours.

Widespread reports of voting delays come as Democrats turn out in record numbers in many states to choose a nominee to face President Donald Trump in November. They also come amid renewed allegations of voter suppression in the United States.

Caren Short, senior staff attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center, notes that voting problems tend to affect similar demographics in state after state.

“If you look where the longest lines take place, it’s almost always in places with a disproportionate number of voters of color, poor voters, young voters and voters with less access to transportation,” Short said.

A historic problem

Voter suppression is nothing new to U.S. politics. Suffrage for non-landowners didn’t come until 1828, and it wasn’t until the 15th amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1870 that denying the right to vote based on race and color was prohibited.

Even after the 15th Amendment, poll taxes and literacy tests disenfranchised poor and minority voters. Of the 330,000 black residents of Mississippi in 1946, only 30,000 could vote.

This changed with the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, prohibiting racial discrimination in voting.

“A very important piece of that Act,” Short explained, “was a handful of states that had previously restricted the right to vote were now required to obtain federal approval before making any changes to their local election laws.”

The law allowed the federal government to veto restrictive barriers to voting. Before 1965, only 23% of African Americans voted in America. That number jumped to 61% by 1969, giving black voters political clout they hadn’t had since the aftermath of the Civil War.

This provision lasted for nearly 50 years, before the U.S. Supreme Court deemed in the 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision that this protection was no longer necessary.

But Short believes data from the last seven years show otherwise.

New rules

The Brennan Center for Justice reports 25 states have enacted new voting restrictions in the last decade. Since Shelby v. Holder, these restrictions include new ID requirements, cuts to early voting, the purging of voters from state databases and a dramatic rise in polling place closures.

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights notes that 1,688 polling locations have closed in 13 states in the last six years, and that those closures disproportionately take place in districts with growing populations of minority or young voters, leading to longer voting lines.

Many Republican lawmakers see these restrictions as a necessary defense against fraudulent voting. In a 2017 op-ed in The Dallas Morning News, for example, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott wrote, “Ensuring the integrity of the ballot box is one of the most fundamental functions of the government. We must do more to ensure that there is no illegal voting in Texas.”

Civil rights organizations, however, insist there is no data to substantiate claims that voter fraud is a serious threat.

“It is very, very rare,” Short said, adding that a lack of uniformity in how voting is conducted is a far bigger threat. “Rules are different from state to state, and even from county to county. It’s confusing to voters, but it also makes it difficult to communicate accurate information and to properly train poll workers.”

Many states, many problems

In Michigan, the long lines were partially being blamed on more than 10,000 voters taking advantage of a new law that allowed them to register on the same day as the primaries, slowing down voting as they completed lengthy paperwork.

Alabama and Mississippi residents reported the moving of polling places to new locations, causing confusion and delays.

In Texas, long voting lines are the subject of partisan debate. Democrats blame Republican efforts to close more than 750 polling locations across the state. Republicans blame county Democrats for assigning the same number of voting machines for both parties, even though Democratic primary turnout was expected to be much higher than that of Republicans, as Trump has faced no serious challenge to his nomination for a second term.

“It’s easy to get caught up in what the intention of certain laws were that caused long lines,” said Abraham Aiyash, statewide training and political director at Michigan United, “but the most important thing to focus on is that whether it was an honest mistake, overwhelmed volunteers or something more nefarious, people haven’t been able to cast their ballot. That, by definition, is voter suppression, and we need to stop it.”

Upcoming elections

In Arizona, which is holding its primary election this week, 20% of polling locations have been closed, mostly in urban centers. Florida controversially eliminated early voting locations on and near college campuses, making long lines more likely Tuesday. Georgia — which was scheduled to vote next week, but whose primary was delayed because of COVID-19 — has reorganized polling stations such that seven counties with large minority populations have only one location to cast their ballots.

Aiyash says states and counties must learn from and fix voting problems before November’s general election, when voter turnout is expected to be even higher.

“If you were overwhelmed in the primaries, imagine what that will look like in November,” he said.

Short agrees. “Some people see long lines as an example of great turnout that should be celebrated,” she explained, “but it’s actually an example of voter suppression. It’s unfair, and it’s damaging to our democracy,” she said.