The stage is set for a volatile American spectacle — public impeachment hearings starting Wednesday targeting U.S. President Donald Trump and whether he abused his office to help himself politically.

The facts of the case are fairly straightforward, but the nuances are many and disputed.

Trump, in a rough transcript released by the White House, asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy in a late July call for "a favor." Trump wanted an investigation of his leading 2020 Democratic challenger, former Vice President Joe Biden, his son Hunter's work for a Ukrainian natural gas company, and a debunked conspiracy theory that Ukraine meddled in the 2016 election that Trump won, and not Russia, as the U.S. intelligence community concluded.

At the time of the call, Trump was withholding $391 million in U.S. military aid that Kyiv desperately needed to help it fight pro-Russian separatists in the eastern part of the country.

Trump never mentioned a specific quid pro quo in the call — the military aid in exchange for the Biden investigation — and for weeks has denied a reciprocal tradeoff. He has described the call with Zelenskiy as "perfect."

But several U.S. diplomatic and national security officials have defied the Trump administration's efforts to keep them from testifying behind closed doors at a Democratic-led impeachment inquiry in the House of Representatives. They have recounted conversations they had with other U.S. officials who said Trump indeed intended to withhold the aid to Kyiv until he got a public statement from Zelenskiy that a probe to help him politically would be launched.

Taylor testimony

The public hearings are set to open with testimony from William Taylor, a decorated war veteran and career diplomat who now is the top U.S. envoy in Ukraine. He told investigators in his closed-door session that while he had not talked directly with Trump about the military assistance, it was his "clear understanding" that Kyiv would not get the military aid unless it launched investigations that would help Trump politically.

He said that Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, had repeatedly told him that while Trump did not view the reciprocal deal as a quid pro quo, "I observed that, in order to move forward on the security assistance, the Ukrainians were told by Ambassador Sondland that they had to pursue the investigations."

Taylor concluded in the closed-door testimony, "That was my clear understanding, security assistance money would not come until" Zelenskiy "committed to pursue the investigation."

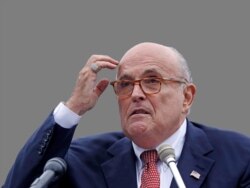

Another State Department official, George Kent, the deputy assistant secretary for European and Eurasian affairs, including Ukraine, also is set to testify Wednesday. He testified privately that Trump's personal lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, engaged in a smear campaign against Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine. Yovanovitch is scheduled to publicly testify next Friday. She was ordered back to Washington earlier this year and dismissed from her posting months before her tenure was set to end. Trump called her "bad news" in the call to Zelenskiy.

Some Trump allies, including Giuliani, named by Trump to oversee U.S. relations with Ukraine, felt she was an impediment to getting Ukraine to open the Biden investigation. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declined overtures from career diplomats to defend her tenure in Kyiv.

Trump has derided the impeachment investigation with an array of invective, that it's a "hoax," a "scam" and just another attempt to undo his stunning 2016 upset election victory over Democrat Hillary Clinton to a four-year term as the U.S. leader. He has derided those testifying against him as "Never Trumpers" or part of "Deep State holdovers" from the administration of his predecessor, Democratic President Barack Obama, even though some of the witnesses against him have served in both Republican and Democratic administrations or have been appointed by him.

Trump's normally staunch Republican supporters have been hard-pressed to settle on a cohesive defense of Trump's call, with some saying there could not have been a quid pro quo because Trump eventually released the aid to Kyiv in September without a public statement from Zelenskiy that a Biden investigation was under way.

Trump named Giuliani as the Ukraine overseer to the dismay of career State Department officials and even some Trump political allies.

Giuliani, the former New York mayor, defended the president's conversation with Zelenskiy. He said on Twitter in September, "The reality is that the President of the United States, whoever he is, has every right to tell the president of another country you better straighten out the corruption in your country if you want me to give you a lot of money. If you're so damn corrupt that you can't investigate allegations our money is going to get squandered."

Dueling narratives

One staunch Trump ally, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, offered a new awkward defense of the president recently, saying, "The Trump policy toward Ukraine was incoherent. It depends on who you talk to. They seem to be incapable of forming a quid pro quo."

But opposition Democrats pursuing his impeachment allege that Trump's actions warrant his removal from office, a drastic action that, while still unlikely, would be a first in the 243-year history of the country. It is illegal under U.S. campaign finance law to solicit foreign assistance for a U.S. political campaign. What's more, Democrats say it is a gross misuse of office for the president to enlist assistance from a foreign government to undermine a political rival in the upcoming presidential election.

The question for lawmakers is whether Trump committed "high crimes and misdemeanors," the standard in the U.S. Constitution for removing a president from office.

The Democratic-controlled House could vote, as political analysts in Washington are predicting, by a simple majority before the end of the year to impeach Trump, an outcome analogous to a criminal indictment in a court case.

The Republican-majority Senate would then hold a trial, but would need a two-thirds majority to convict Trump to oust him from office. With the votes of at least 20 Republicans needed to turn against Trump for a conviction and as yet no Republican calling for his removal, it appears more likely that American voters will decide Trump's fate when he runs for a second term in the November 2020 election, against a Democratic opponent that won't be picked for months.

Anonymous whistleblower

The impeachment inquiry was touched off by an anonymous whistleblower, identified in mainstream news outlets as a man who is a Central Intelligence Agency official who once was detailed to the White House. U.S. law protects the anonymity of whistleblowers who disclose government wrongdoing, but Trump and his Republican allies in Congress have demanded that his name be revealed and that he testify at the hearings. Some conservative outlets supporting the president, along with his son Donald Trump Jr., have disclosed the name of the purported whistleblower, but no one in an official capacity has done so.

The whistleblower's statement was simple and pointedly aimed at Trump, even though he acknowledged he had not been privy to the Trump-Zelenskiy call.

"In the course of my official duties, I have received information from multiple U.S. Government officials that the President of the United States is using the power of his office to solicit interference from a foreign country in the 2020 U.S. election," the whistleblower wrote. "This interference includes, among other things, pressuring a foreign country to investigate one of the President's main domestic political rivals."

Despite Trump's claims to the contrary, much of the whistleblower's statements about Trump's relations with Ukraine and the content of the call have been confirmed by the witnesses summoned for the impeachment inquiry or the rough transcript of the July 25 call between Trump and the Ukrainian leader released by the White House.

Schiff's orchestration

Trump has often assailed the leader of the House impeachment probe, Congressman Adam Schiff of California, chairman of the House Intelligence Committee.

But Schiff has offered Republicans a chance to call witnesses to defend Trump in hearings that could last several weeks.

"Those open hearings will be an opportunity for the American people to evaluate the witnesses for themselves, to make their own determinations about the credibility of the witnesses, but also to learn firsthand about the facts of the president's misconduct," Schiff said.

"Most of the facts are not contested," he said, contending that the central allegation centers on Trump "trying to get Ukraine to dig up dirt on a political opponent."

Trump remains adamant in his angry denunciation of what is about to happen, however, the public hearings aimed squarely at his presidency.

"This Witch Hunt should not be allowed to proceed!" he fumed on Twitter.