Originally from Honduras, Oberlina lives in the U.S. state of Ohio. In 2018, she traveled with a migrant caravan to the U.S.-Mexico border, where she petitioned for asylum. Last week, the mother of two received a phone call from federal authorities.

Her children, ages 6 and 11, had crossed the border into the United States, unaccompanied.

“Immigration officials called me, and they said the children were OK. The next day they called me again. And they told me the children were feeling very sad. I talked to them through tears and so much anguish. I gathered all my strength to tell them not to lose hope,” Oberlina told VOA.

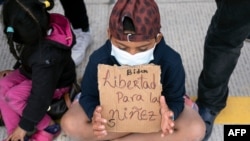

Oberlina’s children are among thousands of unaccompanied minors who have crossed America’s southern border so far this year in what has become an early and thorny challenge for President Joe Biden. Critics as well as some allies of the administration are calling the situation a crisis.

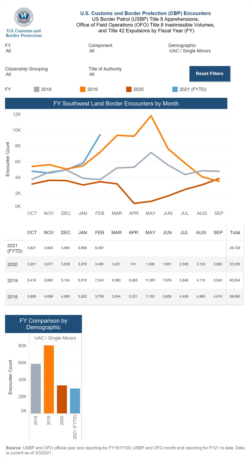

Republican lawmakers have repeatedly faulted Biden's easing of former President Donald Trump's restrictive immigration policies, saying the new administration all but invited an influx of migrants. At a news conference Thursday, Biden rejected the charge, noting seasonal increases in border arrivals.

"It happens every single, solitary year - there is a significant increase in the number of people who come to the border in the winter months of January, February, March," Biden said.

In a statement Wednesday, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said, as of March 23, there were 11,551 minors in HHS custody and 4,962 held at border patrol facilities.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), 29,792 unaccompanied children were encountered on the U.S. side of the border with Mexico from last October through February. Nearly 3,000 were younger than 12 and more than 26,000 were between 13 and 17 years old.

On Wednesday, Biden tapped Vice President Kamala Harris to head the administration’s response to the influx of unaccompanied migrant youths, the only category of asylum-seekers currently allowed to pursue claims in the United States.

While Washington scrambles to address the situation at the border, Oberlina said she is focused on being reunited with her children and hopes they will be released to her in about a week.

Exemption for minors

For most of 2020, the former Trump administration blocked asylum-seekers of all ages under Title 42, an emergency measure implemented in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

The Biden administration kept the policy but exempted minors. Today, federal agencies are struggling to house hundreds of migrant youths intercepted daily at the border, comply with strict rules governing where and how they are cared for, and observe pandemic protocols.

“Border patrol can't handle all the children,” said Dylan Corbett, founding director of Hope Border Institute, based in El Paso, Texas.

Unaccompanied minors, like Oberlina’s children, are afforded special protections and treatment arising from a 1997 federal court decision that limited the length of time children can be held in adult detention facilities.

“In the 1990s there was a lawsuit, which is known as Flores, that was brought on behalf of children who were being held in regular immigration detention with adults and with other kids and they were languishing there for a really long time, months at a time,” explained immigration lawyer Becky Wolozin of the Legal Aid Justice Center. “And this case was brought on their behalf because it's not appropriate to have children in a jail, basically.”

As with all who cross the U.S.-Mexico border without authorization, minors are first taken to a border patrol station. Within 72 hours, however, they must be transferred to the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement under the Department of Health and Human Services and placed in facilities designed to accommodate the needs of children.

The Biden administration has scrambled to expand juvenile shelter facilities, going so far as to consider U.S. military bases, convention centers and hotel complexes as emergency sites. For now, however, U.S. officials concede they are not meeting the 72-hour transfer window for a significant number of minors.

“HHS can't process the children quickly enough. You have more and more children spending time in border patrol facilities, and they're only supposed to be there 72 hours, and the reason it's 72 hours is exactly because the Border Patrol is not equipped to deal with children,” Corbett said.

Foster services

In addition to government-run facilities, some unaccompanied minors are placed in foster care programs until they are released to relatives in the United States.

Tawnya Brown is senior vice president of global refugee and immigrant services at Bethany Christian Services, one of many nonprofits that work with the U.S. government to provide transitional foster care.

“They [migrant children] just go through multiple hands at the border. They go through detention. They go through all these circumstances until they can get somewhere –where, we would hope, is a small bed [at a] shelter or a transitional foster care,” Brown said.

Hundreds of American foster families have taken in migrant children on a short-term basis. Among them are Kim and Jason, a couple in Pennsylvania. VOA is withholding their last name to protect the youths they foster.

“I can't imagine having the weight of the world on my shoulders traveling as a child, across borders, to a place I don't know, and I don't speak the language and everything else,” Jason said.

The last six minors the couple took in were between 15 and 17 years old.

“I've learned to lay off when they first come in and give them space,” Kim said. “I just do it little bit by little bit because I realized that when they come in, there's only so much that they can process, remember, and handle.”

First-hand experience

Sixteen-year-old Jose Luis took a plane, then a bus, and finally walked across the U.S.-Mexico border. Like other unaccompanied minors, he made the journey without parents to guide or protect him.

Though most unaccompanied children arriving at the border originate in Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador, Jose Luis is from Ecuador. He crossed the border alone at the end of January. With this father’s permission, VOA spoke with him about his journey to be reunited in the U.S. with parents he hadn’t seen since he was 3 years old.

“In immigration custody, there’s a lot of children, older children, and adults. There is a bit of everyone trying to cross to the United States,” he said.

After his release from U.S. custody, Jose Luis was met by his parents at New York’s LaGuardia Airport on March 3, an event that featured balloons, gifts, hugs and tears.

“Meeting my mother and my father was the best thing that happened to me today,” he told VOA. “It is the best feeling because of the happiness we can only feel with our parents. Because they’re the ones who gave you life. They’re the ones who support you to move forward no matter what.”

Celia Mendoza contributed to this report.