Excitement over China’s digital advances was rampant when Keith Krach last visited China as chief executive of the highly successful software company DocuSign, with its more than 400 million users in 188 countries.

“I saw a lot of new technology. I saw the drone swarm technology. Everybody was telling me to download Tencent every 30 minutes,” Krach said. Tencent is the multinational conglomerate behind China’s popular WeChat app.

That was in December 2017. Today Krach is near the top of a list of Americans who are banned, along with their close relatives, from ever again visiting China or doing business with Chinese entities.

Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo “was number one, [former trade policy adviser Peter] Navarro number two, I'm number three" on the list topped by former Trump administration officials, Krach said in a recent interview.

Twenty-eight people were hit with the sanctions, which were announced January 20, minutes after U.S. President Joe Biden was sworn in.

'Shot across their bow'

While the sanctions were focused on those leaving office, Krach said he believed they were meant as a warning to members of the incoming Biden administration, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken and White House Asia coordinator Kurt Campbell.

“That’s a shot across their bow — you know, just enough to make them hesitate — and that makes a difference. For me, it doesn’t affect me. I’m at a different station in life,” Krach told VOA during a recent visit to Washington.

Krach became a U.S. undersecretary of state for economic affairs in March 2019 and stayed on the job until the end of President Donald Trump’s term.

“My charge was to develop an operationalized global economic security strategy to drive global economic growth, maximize national security and combat China’s economic aggression,” he said.

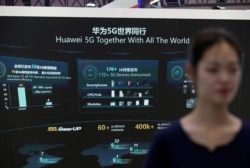

A year into the job, “the issue of 5G became really urgent,” he said. “Huawei had announced that they had 91 worldwide contracts, 47 in Europe. It looked like they were unstoppable, [that] they were going to run the table.”

Krach’s job was to turn the table.

The United States started warning allies and partners in 2019 that having the Chinese telecom firm Huawei build their 5G telecom infrastructure risked exposing their citizens’ and their official data to Chinese state surveillance. The Trump administration argued that countries should keep Huawei out, both for their own sake and for the sake of collective security among democratic allies.

Huawei has repeatedly asserted its independence from China’s government, even though it is branded in China as a “state champion” and has a Communist Party administrative department embedded in its corporate structure.

One by one, Krach and his team enlisted dozens of allied countries and telecom corporations in what became known as a Clean Network. “By the time we’re done, [Huawei] had probably about a dozen and a half” contracts left, down from nearly 100, Krach said.

Building what U.S. officials called an “alliance of democracies” to ensure technological independence from Chinese state-backed firms wasn’t always easy. If, as Krach said, the Chinese authorities tried to intimidate incoming U.S. officials, the same scare tactics were used on government officials and businessmen in other countries.

Fear of retribution

“It was pretty clear in those bilateral meetings that everybody was afraid to talk about China or Huawei. The elephant in the room was China’s retribution, retaliation,” Krach recalled. “So a big part of the Clean Network is [providing] a ‘security blanket’ because there’s strength in numbers and there’s power in unity and solidarity.”

NATO Deputy Secretary-General Mircea Geoană and EU Commissioner for Internal Markets Thierry Breton were natural allies who needed no convincing that the political, economic and security alliance among democracies was only “as strong as our weakest link,” Krach said.

But to effectively counter Huawei, the alliance of democracies also needed to control the technology and hardware needed to build 5G systems. Krach said the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company was persuaded to build a cutting-edge plant in the U.S. while the Trump administration put in place export controls depriving Huawei of essential semiconductors and related technology.

“First you see Huawei beginning to lose the momentum, then you see the tide beginning to turn, then the tide is turning, then the tide is turned,” he said.

Krach believes that confronting the “China challenge” will require a continuing bipartisan effort by the two U.S. political parties, and he hopes his efforts as undersecretary for economic affairs have provided a “head start” for the Biden administration.

He also hopes the “alliance of democracies” can continue to flourish, and that Biden’s “buy American” initiative can be combined with the purchase of products from allied nations and partners. “Why not do free trade among the Clean Network?” he said.

Journey from Ohio

Krach was born in April 1957 in what he described as “small-town Ohio.”

“My father ran a machine shop, and my mother was a teacher," he said. "My dad’s customers were suppliers to the Big Three car companies in Detroit, and his fortunes were tied to theirs. ... In boom times, we scrambled to fill big orders; in bad times, I was his only employee.”

Krach told members of the U.S. Senate at his confirmation hearing that his father “dreamed that I would get some ‘college knowledge’ and return as an engineer to help him grow the machine shop into a big company of 10 employees.”

The son never returned to work with dad in Ohio but instead went on to become the youngest vice president at General Motors and later a billionaire inventor and corporate CEO before joining the State Department.

Krach is now back in California but takes satisfaction in his time in government service.

“We say in Silicon Valley, 'Corporate responsibility is social responsibility.' Well, corporate responsibility is also national security, because companies wouldn’t be around without the United States, without democracy, without capitalism,” he said.