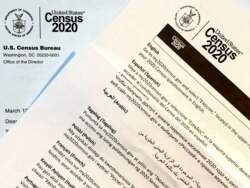

At a Michigan gas station, the message is obvious — at least to Arabic speakers: Be counted in the 2020 census.

"Provide your community with more/additional opportunities," the ad on the pump handle reads in Arabic. In the fine print, next to "United States Census 2020," it adds: "To shape your future with your own hands, start here."

As state officials and nonprofit groups target hard-to-count groups like immigrants, people of color and those in poverty, many Arab Americans say the undercount is even more pronounced for them. That means one of the largest and most concentrated Arab populations outside the Middle East — those in the Detroit area — could be missing out on federal funding for education, health care, crime prevention and other programs that the census determines how to divvy up.

That also includes money to help states address the fallout from the coronavirus.

"We are trying to encourage people not just to fill it out because of all the reasons we had given before, where there's education and health care and all of that, but also because it is essential for the federal government to know who is in Michigan at this point more than ever before," said Rima Meroueh, director of policy and advocacy with Dearborn-based ACCESS, one of the largest Arab American advocacy nonprofits in the country.

The Arab American community checks many boxes that census and nonprofit officials say are hallmarks of the hardest-to-count communities: large numbers of young children, non-English speakers, recent immigrants and those who often live in multifamily or rental housing.

Arabs arrived en masse to the U.S. as the auto industry ramped up and worker demand grew. By the time those jobs began to decline in more recent decades, communities with strong Middle Eastern cultural roots had been firmly established in the Detroit area. It has remained a destination for people from across the Middle East fleeing conflict, reconnecting with family or simply seeking a better life. Even those who resettle elsewhere often first make their way to Detroit and surrounding cities.

Advocates have pressed ahead with "get out the count" campaigns despite restrictions designed to curb COVID-19. The pandemic has forced the Census Bureau to push back its deadline for finishing the 2020 count from the end of July to the end of October. It's also asking Congress for permission to delay deadlines next year for giving census data to the states so they can draw new voting maps.

With the changes, ACCESS is stepping up its social media effort, mirroring it to focus as much on the once-a-decade count as their offices, which had been plastered with census posters, Meroueh said.

"If you check out our social media, it's very census-heavy," she said.

But groups face a hurdle after the Trump administration decided not to include a category that counts people from the Middle East or North Africa as their own group. The Census Bureau recommended the so-called MENA box in 2017 after years of research and decades of advocacy.

The decision to scrap the choice angers many Arab Americans, who say it hinders representation and needed funding. Democratic U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, an Arab American representing part of Detroit and several suburbs, expressed her displeasure while questioning Census Bureau director Steven Dillingham on Capitol Hill in February.

"The community did it right — they went through the process," she said. "You're making us invisible."

Dillingham said the form would have a write-in box, allowing people to describe their ethnicity. It falls short for Tlaib, but Matthew Jaber Stiffler, a University of Michigan lecturer and research and content manager at the Arab American National Museum, said it's better than nothing. Advocates will have to push harder to get people counted, he said.

"The onus is on community organizations, and local and state governments to get the people to complete the form, because it doesn't say, 'Are you Middle Eastern or North African?'" Stiffler said. "We'll get really good data if enough people fill it out."

Even though the MENA option isn't there, Stiffler says census officials did preparatory work for it. If someone writes "Syrian" on their form, for instance, Stiffler has been told that the census will code that within the larger MENA ancestry group.

That's precisely what Abdullah Haydar did when he filled out his census form electronically, which he said took five minutes.

"I definitely filled it out as soon as I got it. I believe in representation," said Haydar, a 44-year-old from Canton Township, Michigan, who works in LinkedIn's software engineering department.

But support for the census isn't unanimous. Some in the Arab community have raised concerns about government questions over their citizenship status if they participate, though that is not part of the form. Many have reported extra scrutiny since the Trump administration issued a ban on travelers from several predominantly Muslim countries in 2017 — creating an overall chilling effect when it comes to interacting with the government.

"They don't trust the current administration. They don't trust what they're going to do with the information. And when you look at the the so-called Muslim ban that was put in, people don't want to be on the government's radar," said Haydar, who assisted some elderly relatives in filling out their forms.

"I just told them, 'Look, yes, there may be abuses. There's always a risk of that. This administration seems to be pushing boundaries. But at the end of the day, this is the basis of our system of government, for people to count,'" he said.