Attorneys on both sides of a dispute over a law called the Indian Child Welfare Act say it could be months before a panel of 16 judges in New Orleans decides the fate of the 40-year-old statute, designed to keep Native American families and communities together.

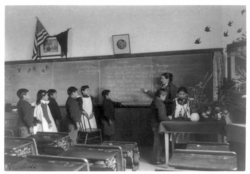

Congress passed the ICWA in 1978 to stop states from placing Native American children in non-Native American families, a practice that had been going on for generations that many Native Americans decried as part of a wider U.S. policy to “civilize” and assimilate them.

In cases where welfare agencies believe it is necessary to remove Native American children from their homes, the law requires them to make every effort to place children with relatives or fellow tribe members.

In 2016, three sets of prospective adoptive parents, each non-Native American and fostering Native American children, along with the states of Texas, Indiana and Louisiana, took the U.S. government to court in an effort to overturn the ICWA.

A U.S. Texas judge ruled in their favor but a three-judge panel in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned his opinion in September, ruling that the law is constitutional because Native Americans are a political group, not a race.

The plaintiffs had a choice at that time of appealing the case "en banc" -- before the full panel of judges in the same court -- or taking their case to the Supreme Court.

They chose the former, and the en banc hearing opened Wednesday.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals is widely recognized as one of the most conservative circuits in the country, said Kate Fort, director of the Indian Law Clinic at the Michigan State University College of Law and co-counsel for the defense.

“The three judges who heard the case initially were probably some of the most moderate judges in the Fifth Circuit, so I think the plaintiffs believed they had a better chance of getting a more favorable decision if they asked for an en banc review."

ICWA opponents have the backing of the Goldwater Institute, an Arizona-based think tank whose stated goals include “advancing the principles of limited government” and “leaving states free to enact laws” that protect citizens’ constitutional rights.

“The Indian Child Welfare Act commandeers states into enforcing federal law, which violates the 10th amendment,” said plaintiffs’ co-counsel Mark Fiddler, who argues that states, not the federal government, should decide child welfare cases. He also argues that the law discriminates against non-Native American families on the basis of race, violating the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause.

"The argument about tribes being a race is based on a real fundamental misunderstanding of precedent in this area,” said Fort.

“Tribe members are citizens of their tribal Nations. The longstanding understanding of tribes and tribal people is that they have a political—or government-to-government—relationship with the federal government based on a history of treaties and the Constitution,” she said.

If ICWA were to be overturned on grounds of racial discrimination, tribes worry this could ultimately undermine their political sovereignty.

It’s a complicated case several years in the making, with both attorneys predicting it could be months before the panel of judges reaches a decision.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr., Morongo Band of Mission Indians Chairman Robert Martin, Oneida Nation Chairman Tehassi Hill and Quinault Indian Nation President Fawn Sharp, co-defendants in Brackeen vs. Bernhardt, issued the following statement at the close of Wednesday’s hearing:

"The legal challenges against the law only further harm Native American children, families and communities. We are confident the court will once again reject this misguided effort and rule on the side of protecting families and children for years to come.”