The late U.S. congressman and civil rights lion John Lewis is being recognized Monday and Tuesday with one of the highest honors a U.S. citizen can receive – lying in state at the U.S. Capitol.

Lewis died last week at the age of 80 after a yearlong battle with advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.

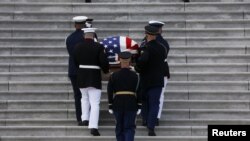

His casket is being brought to the building where he served the people of his Georgia district for 33 years.

In keeping with COVID-19 related safeguards, Lewis will lie at the top of the steps of the Capitol's east front so the public can pay their respects safely outside with social distancing guidelines and mask requirements.

Lewis lay in state Sunday in Montgomery, Alabama, to give the people of his home state a final chance to pay their last respects.

Lewis’ body arrived at the Alabama Capitol shortly after a horse-drawn caisson brought his flag-draped casket across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, the same bridge where police beat him and other civil rights marchers when they tried to cross it during a walk to Montgomery in 1965. That day became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

That day was known as “Bloody Sunday.” No one at the bridge 55 years ago would imagine that one day, a Black man would cross that same bridge in honor, with flags across the state flown at half-staff as a sign of respect for him and all he fought to achieve.

Sunday was the second day of nearly a week of memorials and remembrances for Lewis.

After lying in state in Washington Monday and Tuesday, Lewis will lie in state in the Georgia state Capitol in Atlanta Wednesday, before his Thursday funeral at Ebenezer Baptist Church, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached. He will be laid to rest in Atlanta’s South View Cemetery.

Lewis will be the second Black lawmaker to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol. Congressman Elijah Cummings, who died last year, was the first.

Two memorial services were held for Lewis Saturday in Alabama, where he was born in 1940.

At the public service at Troy University, five siblings and a great-nephew spoke of Lewis as a loving and fearless family man.

"He'd gravitate toward the least of us," said brother Henry "Grant" Lewis. "He worked a lifetime to help others."

His brother Samuel said his mother had warned John “not to get in trouble, not to get in the way.” Samuel Lewis added that his brother did not heed their mother’s warning, saying, “We all know that John got in trouble, got in the way, but it was a good trouble.”

The Lewis siblings reminded the crowd of their brother's famous injunction to make "good trouble" — ruffling feathers when it was for a righteous cause.

Lewis had wanted to attend Troy University, in Troy, Alabama, his birthplace, but was denied admission to what was then a whites-only school.

Lewis, who as a young boy preached to the chickens on his family’s farm, eventually earned a degree from Fisk University, in religion and philosophy. Years later, Troy University bestowed an honorary doctoral degree on Lewis.

Senator Doug Jones from Alabama said the current crop of protesters “are protesting peacefully, nonviolently,” as Lewis did during the civil rights movement.

President Donald Trump “paints them all with a broad brush and calls them thugs, but he is wrong,” he said, “They are patriots who want America to move forward to a nation of equals together.”

At Troy University, Lewis lay in repose as visitors paid their respects. A private ceremony honored him at a chapel in Selma, Alabama, ahead of another public viewing Saturday.

Lewis rose to fame as a leader of the modern-day American civil rights movement of the 1960s. At 23, he worked closely with King and was the last surviving speaker from the August 1963 March on Washington where King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

The civil rights movement led Lewis into a career in politics. He was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1981 and to Congress in 1986, calling the latter victory “the honor of a lifetime.” He served 17 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia’s fifth district.