Enacted in 1965, the Voting Rights Act has long been hailed as the most successful piece of civil rights legislation ever passed by the U.S. Congress. Within just months of its approval, the law enabled hundreds of thousands of disenfranchised African Americans to register to vote, a change so dramatic that one political scientist termed it the "Second Reconstruction."

But as the law turns 56 this month, voting rights advocates say the historic legislation faces the most serious existential peril yet. The threat, they say, comes from a wave of restrictive voting rules adopted by states across the nation, and a conservative-controlled Supreme Court that has steadily chipped away at the legal protections of the legislation signed into law by Democratic President Lyndon Johnson.

"We see many of the same forces, many of the same elections practices that inspired the original Voting Rights Act of 1965 and compelled President Johnson and members of Congress to work towards its passage," said former U.S. Representative and Democratic presidential candidate Beto O'Rourke of Texas.

Republican leaders and activists dismiss such allegations, insisting that the changes being sought will instill more integrity and transparency in the voting process and prevent the possibility of fraud. With its new election overhaul law, "Georgia will take another step toward ensuring our elections are secure, accessible and fair," Georgia Governor Brian Kemp said in late March.

Hundreds of Republican bills

This year, Republican state lawmakers in 49 states have introduced nearly 400 bills under the rubric of election reform that the left-leaning Brennan Center for Justice contends would make it harder for many Americans to vote. Of these bills, 30 have been signed into law — more than the number enacted in 2011, when Republicans rolled out a similarly sweeping legislative effort.

This drive — which critics say will curtail voting opportunities for millions of voters, especially African Americans and other minorities — was spawned by former President Donald Trump's baseless claim that he was denied reelection in November 2020 because of a "rigged" election and massive voter fraud.

With Democrats sounding the alarm about voter suppression, President Joe Biden in mid-July traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — a city known as the cradle of American democracy — where he gave a speech denouncing what he termed an assault on hard-won voting rights.

"The 21st century Jim Crow assault is real," Biden said, using a term referring to 19th- and 20th-century racial segregation that activists also use to describe modern-day voter suppression tactics. "It's unrelenting, and we're going to challenge it vigorously."

Republican officials behind the growing suite of laws deny they are intended to undermine voting rights. Instead, they say, the new rules — such as tighter ID requirements, restrictions on absentee voting, purging of voter registration lists, and other changes — are meant to prevent fraud and restore public confidence in elections.

Texas a hotbed

Texas has emerged as a hotbed of Republican efforts to enact highly restrictive new voting laws, so much so that more than 50 Democratic state lawmakers from Texas fled the state for Washington, D.C., to deny Governor Greg Abbott and the Republican majority a legislative quorum to vote on a new set of regulations.

"Texas is making it EASIER to vote & harder to cheat," Abbott tweeted after Biden called out his state during his speech.

A multitude of studies and court cases, however, have shown that to the extent that voter fraud exists in the U.S., it is trivial in scale.

The Voting Rights Act, one of three major civil rights laws passed in the 1960s during the Johnson era, was the culmination of a long battle for Black civil rights, according to political scientist Todd Shaw. Indeed, voting rights were a key part of the struggle.

"In fact, absent the activism of the civil rights movement, it is arguable that the act would not have passed or certainly wouldn't have passed in the time frame that it did," Shaw, a professor at the University of South Carolina, said in an interview.

Rights not for all at first

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, did not originally guarantee everyone the right to vote. However, in 1870, following the American Civil War, the 15th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, giving all male citizens the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." Along with other measures, this fueled what many historians see as the largest expansion of civil rights in U.S. history.

Selma

But that monumental achievement proved fleeting, as white Southerners, determined to keep Blacks from the polls, instituted literacy tests and other barriers to voting, setting off a long struggle for civil rights.

A turning point in the movement came on March 7,1965, when a group of 600 activists, marching peacefully from Selma, Alabama, to the state's capital, Montgomery, was violently attacked by police, some on horses, while crossing a bridge leading out of town. A young John Lewis helped lead the marchers. He suffered a skull fracture, becoming one of 58 people treated for injuries. Lewis later went on to become a prominent civil rights leader and member of Congress.

Images of the incident that became known as "Bloody Sunday" were televised around the country, causing a national outcry that helped mobilize support for voting rights legislation.

"It was worth the suffering of so many people. It was worthy of the blood that some of us gave," Lewis said in a 2015 interview with VOA.

On August 6, 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, the strongest voting rights legislation ever.

Enforcing the 15th Amendment

The legislation, "an act to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution," outlawed practices and procedures that "deny or abridge" the right to vote based on race or color. It suspended the literacy tests used in Southern states that had made it virtually impossible for many Blacks to register to vote.

Breaking new ground, the legislation included two other key provisions, known as Section 4 and Section 5, that took aim at Southern states that had a history of racial discrimination. It required them to get federal approval for any change in their voting laws and policies.

Finally, the new provisions authorized the appointment of federal "examiners" tasked with, among other things, registering Black voters.

Marc Morial, a former mayor of New Orleans who now heads the National Urban League, said the two provisions formed the bedrock of the voting rights law.

"They made democracy fair, level and evenhanded," Morial told VOA.

Impact almost immediate

To be sure, long before the Voting Rights Act took effect, many African Americans, including southern Blacks, voted in elections. But if the law was intended to expand their access to the ballot box by removing institutional barriers to voting, it was widely seen as an unqualified success.

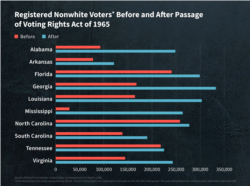

By the end of 1965, some 250,000 new Black voters had been registered, one-third of them by federal examiners, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

As Black registration surged, the gap between registered white and Black voters in former Confederate states, hovering around 30% at the beginning of the 1960s, closed to less than 10% by 1970, according to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies.

The spike in Black voter registration in turn led a larger number of African Americans to run for office, according to Shaw. In 1966, Edward Brooke became the first African American elected to the Senate since Reconstruction.

"By the early 1970s, you had so many African Americans being elected to Congress that you had the formation of the Congressional Black Caucus," Shaw noted.

At the same time, the Justice Department used the Voting Rights Act to block "scores" of discriminatory voting changes across the South, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University.

From the beginning, the law was met with resistance. But during the 1960s, the Supreme Court dismissed multiple legal challenges to the legislation, while Congress repeatedly reauthorized it. Congress added protections for language minorities and people with disabilities.

A key 1982 amendment to Section 2 banned voting practices and procedures that "resulted" in discrimination, regardless of whether they "intended" to discriminate. This allowed legal challenges to a host of voting practices on the grounds that they had "discriminatory effects."

Shelby County v. Holder

Then, in 2013, the Supreme Court took an ax to the law, voting 5-4 to invalidate Section 4, the provision that determined which jurisdictions needed to get federal approval for changing their voting laws. In the half century since the Voting Rights Act's passage, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that "things have changed dramatically" in jurisdictions subject to the law, making the requirement unnecessary.

Even before the Supreme Court handed down its decision, Republican-controlled states had begun tightening voting rules. This early wave of voting restrictions came in response to the 2008 election of Barack Obama, the first African American president, according to the Brennan Center.

To voting rights advocates, the Shelby County decision was a devastating blow. The ruling, said Morial, unleashed a "tsunami" of voter suppression laws "in state after state after state." Within hours of the ruling, Texas announced that it would immediately implement a tough photo ID requirement that had been blocked under the Voting Rights Act. Soon, other states followed suit.

In the years that followed, voting rights groups turned to another enforcement mechanism of the Voting Rights Act to challenge what they viewed as discriminatory election laws: Section 2. That provision prohibits discrimination in voting.

But then this year, the Supreme Court upheld two Arizona voting rules that had been challenged under Section 2. The first rule discounts votes cast in the wrong precinct. The second makes it a crime for anyone other than family members or caregivers to collect a voter's ballot, a practice known pejoratively as ballot harvesting.

Democrats argued that both rules disproportionately impacted minority voters in violation of Section 2. But the six conservative justices of the Supreme Court rejected the argument that the voting laws imposed undue burdens on voters.

"Arizona law generally makes it very easy to vote," Justice Samuel Alito wrote, noting that Arizona's out-of-precinct policy was affecting 1% of minority voters.

J. Christian Adams, the conservative president of Public Interest Legal Foundation, which filed an amicus brief in the Arizona voting rights case, said that Democrats and voting rights groups have used "statistical modeling" to challenge voting laws on the grounds that they have a disparate impact on racial minorities.

"But the courts have never, ever allowed that to happen," Adams said in an interview. "For there to be a violation of the Voting Rights Act, somebody actually has to have their vote denied. It's not just a statistical game, where you look to see how a law affects racial subsets."

Voting rights advocates worry the Arizona decision will make it harder to challenge other state voting procedures. The Justice Department recently challenged the new Georgia election law under Section 2.

"It's almost as if the court is telling us, without saying it, that it doesn't believe that racial discrimination is still quite the issue that it was, that it doesn't believe somehow that these legal provisions are still needed," said Damon Hewitt, president and executive director of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

Dim prospects in Congress

Viewing the Supreme Court as hostile to voting rights, Democrats have introduced two pieces of legislation in Congress to protect the gains of the Voting Rights Act. The John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would once again require certain jurisdictions to obtain federal preapproval for changing their voting rules.

A more sweeping piece of legislation, known as the For the People Act, would create automatic voter registration across the country, restore voting rights to felons who have completed their sentences, and expand early and absentee voting, among other measures.

But with Republicans in vigorous opposition, the odds are stacked against the proposals' passage this year. And unless President Biden has a change of heart and supports elimination of the filibuster, Democrats will be unable to muster the 60 votes needed to enact legislation in the Senate.

Nevertheless, voting rights activists remain optimistic that voters will turn out for the 2022 midterm elections, despite all the obstacles, much as they did in record numbers during the 2020 presidential election.

"I also want to focus on the amazing amount of turnout that happened in the last election and the positive reforms that are being moved around the country and the interest and excitement that people have when talking about elections and voting rights right now," said Sylvia Albert, director of voting and elections at Common Cause, a government watchdog group.