On October 13, 1652, after a day of fasting and prayer, 15 Native American men stood before a panel of Puritan church officials in Natick, Massachusetts. They had come to confess their sins and prove their commitment to Christianity.

One of them was Waban, a member of the Nipmuc tribe.

“Before I heard of God and before the English came into this country, many evil things my heart did work, many thoughts I had in my heart; I wished for riches, I wished to be a witch, I wished to be a sachem [chief]; and many such other evils were in my heart,” Waban stated.

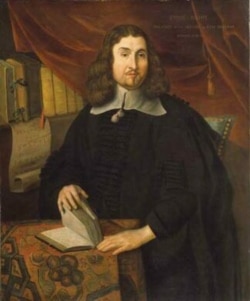

Missionary John Eliot, who claimed proficiency in the local Algonquin dialect, translated the Native Americans’ statements, later publishing them as “Tears of Repentance.”

History has dubbed Puritan missionary Eliot as “the apostle to the Indians” and celebrated him as the founder of the American missionary movement. Many Native Americans and some historians today see him as an agent of cultural genocide. The descendants of those first Christian converts, however, tell a different story.

Missionary goals

Even before they arrived at Plymouth in 1620, the Pilgrims drew up a temporary set of laws, stating that one of their goals was to advance Christianity.

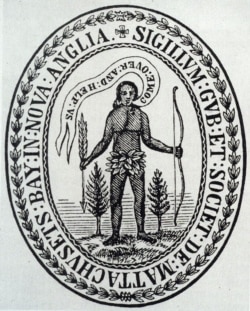

Nine years later, a separate group of Puritans settled in what is now Boston to organize the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Their charter spells out their intention to “win and incite the Natives of the country to the knowledge and obedience of the only true God and Savior of mankind.”

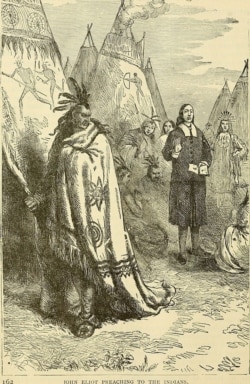

In 1646, John Eliot gave his first sermon to a skeptical Native audience near present-day Boston.

“They gave no heed… but were weary, and rather despised what I said,” he wrote.

Next, he approached Waban in his village of Nonantum (now Newton, Massachusetts). Waban, too, resisted.

“When the English taught me of God… I would go out of their doors… angry with them,” Waban later confessed. But not long after, an epidemic struck his tribe, and Waban changed his mind.

“I considered what the English do, and I had some desire to do as they do; and after that, I began to work as they work… then I thought I shall quickly die, and I feared lest I should die before I prayed to God,” he said. Within a few years, Waban was preaching and bringing in converts himself.

Eliot believed that for Native Americans to be true Christians, they should leave their cultures behind. In 1650, Eliot established the first of 14 so-called “praying towns,” where converts would live, eat and work as Englishmen. He expected the “praying Indians” to follow the Ten Commandments and imposed fines or corporal punishment for offenses such as idleness, adultery, domestic abuse or wearing their hair the wrong way.

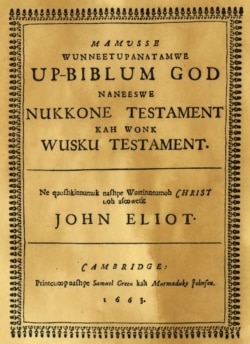

Because tribes had no written language, Eliot studied their language and, with help from several bilingual Native Americans, wrote down grammatical rules and, ultimately, translated the Bible and other religious texts.

Confessions

As a final step, the converts were required to make confessions; only then were they given full Church membership. But how accurate are Eliot’s translations?

“I did understand most things that some of those Indians spake; and though others spake not so well to my understanding, yet many things I understood of what they all spake: and thus much I may testify, that (according to what I understood) the substance of their Confessions is here truly set down,” Eliot wrote.

George E. Tinker, a citizen of the Osage Nation, professor emeritus at Denver’s Iliff School of Theology and author of “Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Cultural Genocide,” believes Eliot embellished their statements to suit financial backers in England.

“If you go back and look at the confessions, the actual words of the confessions violated the Natives’ own culture,” he said. “It is the English fantasy of what pagan savages do or did.”

He also doubts that Eliot’s intentions were entirely religious.

“Eliot was paid by the Massachusetts Bay Colony general council to go out and convert Indians,” Tinker said. “Christianization has always been the liberal solution to the so-called ‘Indian Problem’ — a missionary can tell you to put your weapons away because you are Christians now, and we live by the grace of God.”

Some scholars have suggested that Puritan ideology, which emphasized eternal damnation for sin, may have frightened Natives into converting.

It should also be noted that only a quarter of New England Native Americans converted to Christianity. The rest remained faithful to culture and traditional belief systems.

A ‘praying Indian’ speaks

A group of lineal descendants of those early converts today has organized as the Praying Indian Tribe of Natick, led by Chief Caring Hands (Rosita Andrews), who told VOA she received her title from her mother.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Native Americans on reservations underwent forced conversion in boarding schools, but she said her ancestors’ experience was very different.

“We were not forced, coerced or anything else,” Caring Hands said.

A devout Christian, she believes that when Waban heard Eliot preach, he had what would be called a “religious experience.”

“It was the spirit coming upon him. And we know this. We know what it is,” the chief said.

‘Betrayal’

In 1675, relations between Puritans and praying Natives were upended by the brutal war of resistance known as King Philip’s War.

Fearing the Christianized Native Americans would turn against them, Puritans imprisoned hundreds on Deer Island in Boston Harbor, where many died from disease, starvation or exposure.

With Eliot’s help, survivors later returned to find their towns dissolved and lands taken. Some moved on, while others remained in Massachusetts.

Waban remained a “zealous, faithful” Christian until his death.

Today, Caring Hands and other Praying Indian Tribe members gather annually at Deer Island to commemorate what she calls “a betrayal of the first order.”