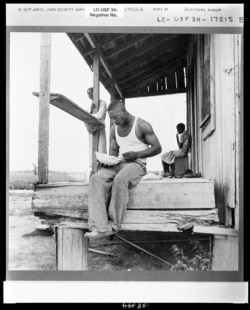

By the late 19th century, slavery was over, but the American South was still rife with discrimination and injustice for rural African American sharecroppers.

“They could only shop at one store, the country store, where prices were high,” says Louis Hyman, an economic historian and assistant professor at Cornell University.

“It often was the case that the landlord also owned the store, and their lives were ruled by credit. They basically could only shop at that store because their accounts would not be reconciled until the cotton crop came in. Because of that, they didn't really have cash, and they really didn’t have an alternative way to get credit.”

Enter Sears, the department store chain founded by Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck in 1893, which had a catalog that offered black sharecroppers an alternative. Sears let customers buy on credit, which gave African Americans the option to bypass the local country store, where black customers had to wait until the white customers were served.

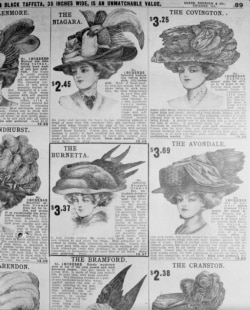

“They couldn't buy the same clothes as white people. They couldn't buy the same food as white people...This was part of the sort of everyday white supremacy of Jim Crow,” Hyman says. “And so, the Sears catalog allowed them a way to buy clothes that were nicer than were available in that country store, to buy food that the white people ate... It offered them a choice where they didn't have to feel second-class in their shopping lives.”

The Jim Crow laws, which were in effect from the 1880s to the 1960s, were state and local mandates that enforced racial segregation in the American South. The most common types of these laws outlawed intermarriage and required businesses and public institutions to separate their black and white patrons.

Sears, the department store founder, was not motivated by social justice. As a businessman, he was in it for the money. Once Sears realized that African Americans were using the catalog to avoid discrimination at the hands of white supremacists, he took steps to make sure they could continue to shop the catalog.

Sears set up systems that gave black patrons the option to go directly to the postal carrier, completely bypassing the country store, which in some cases, was also the post office.

Rumors spread that Sears and Roebuck were black, presumably to convince white shoppers that they shouldn't shop at Sears. Sears and Roebuck published pictures to prove they were white.

“It's easy to think of Jim Crow as just taking away the vote from African Americans, but it was part of an everyday kind of experience of difference that legitimates a kind of hierarchy,” Hyman says, adding that African Americans have always had a less equal access to the market.

“This is what racial segregation is all about. You see that today. Where are the food deserts? In cities. Why don't black people have access to the same kinds of stores that white suburbanites do? And a lot of the experience of black people is an experience of monopoly, not being able to get to a bank, having to rely on a check-cashing place, not being able to get to that slightly better-paying job because they're isolated in terms of transportation or neighborhood.”

Last October, Hyman tweeted about the Sears catalog’s role in battling white supremacy. The thread went viral on Twitter and was seen by millions. Actor LeVar Burton was among those who retweeted it.

“I think the reason it connected with people is that people still shop while black, they still get trailed through stores,” Hyman says. “We still have this daily experience of not being welcome and being forced to feel second-class.”

Hyman says it’s not a coincidence that the Sears catalog began to decline after the end of the Jim Crow era. Some on the Twitter thread suggested that Amazon shopping can play a similar role for African American customers today as the Sears catalog did more than a century ago.